About

Global Team

Roberta d’Eustachio

Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Roberta d'Eustachio (Rd'E) is an entrepreneur obsessed with delivering media from the social investor/philanthropist's point of view. That desire led to founding The American Benefactor, the first consumer magazine for philanthropists, as well as Giving Magazine and each of its subsequent evolutions: from print, to digital, to mobile with Facebook Instant Articles, delivering stories of social impact - for everyone, everywhere.

Rd'E has consulted with, and/or received investment from, leading global brands, including: The Economist, the Financial Times, Euro Money/Institutional Investor, the Pitcairn Family Office, Fidelity Capital and the World Bank as well as philanthropists and social enterprises around the world.

After serving as chief-of-staff to Dame Stephanie Shirley, the British Government’s Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy, Rd'E founded the AmbassadorsForPhilanthropy.com enterprise to give social investors a voice worldwide.

Dame Stephanie Shirley

Philanthropist & Believer-in-chief

Dame Stephanie “Steve” Shirley is a British entrepreneur turned philanthropist. She originally arrived in London as an unaccompanied Kindertransport child refugee from Austria during WWII. “Steve” was an early pioneer in technology and, after taking her company public, she has given more than $100 million to organizations that specialize in autism research and technology, including founding the Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University. Appointed by Prime Minister Gordon Brown to the title of the British Government's Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy 2009-2010, she believes in the advancement of the philanthropist voice worldwide.

Her memoir “Let It Go” was recently published, chronicling her life so far.

"Steve" is the Believer-in-chief to Giving Magazine, providing the means to imagine and execute its potential to the fullest.

Jerry Alten

Chief Curator

Jerry Alten is a world-renowned art director of magazines, across all devices, and other marketing and advertising work, winning many prizes in the media field. Under Walter Annenberg’s ownership of TV Guide, Jerry took the circulation from 5 million up to 19 million during his tenure as art director. He continued to work with Rupert Murdoch’s organization after the buy out of TV Guide and created the first interactive website for the magazine. Jerry was also the original investor in The American Benefactor Magazine and art director, which succeeded in obtaining more than $7 million worth of investment from Fidelity Investment's venture firm.

Brian Lipscomb

Chief Technologist

Brian Lipscomb has been involved with technology for over twenty years, and founded technology services company Divergex, based in Philadelphia. Specializing in all aspects of computers, Brian brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to Giving Magazine. His philosophy is: “Do it right, or don’t do it at all.”

Lipscomb adds: “Technology is a constantly evolving industry. People who use technology daily don’t have the time to study and learn all of the new and different terms and capabilities. I work to show people how technology can improve their efficiency, productivity and, ultimately, their lives.”

Jay Balfour

Managing Editor

Before Jay became the Managing Editor for Giving, he was a freelance writer and editor based in Philadelphia. With an academic background in Philosophy he leverages an informed perspective on everything from African music to youth movements in the West for several publications both online and in print. At Giving Magazine he shares a passion for unabated reporting and the ushering in of a new age in philanthropy.

Sandra Salmans

Executive Editor

Sandra Salmans is a New york-based writer and editor who works primarily in the nonprofit field. She began her career as a business and financial journalist at Newsweek and The New York Times, but has also covered national news, education and the arts. Prior to going freelance, she was a senior officer in communications for a leading foundation in Philadelphia.

Nicole Raeder

Digital Design Manager

Nicole delights in great design. That's why her commitment is compulsive; contagious even, to get it right. Or, change it. Or, change it again. Whatever is required to finding the way to the end point, which is sometimes the beginning. In other words, she never gives up, or stops, till the thing clicks.

She also loves cats.

Damon d'Eustachio

Co-Director, Global Membership

A foodie who navigated his way from the city of brotherly love to Charleston, S.C, Damon is devoted to serving nonprofits worldwide that believe the philanthropist voice must be heard.

Damon graduated from the College of Charleston in Art Administration and performed an internship at London’s prestigious Tate Gallery’s New York City office.

Jessica Lambrakos

Co-Director, Global Membership

Jessica is responsible for the management and development of the Global Awards for nonprofits of Giving Magazine for their nominated philanthropists and supporters.

She also serves as founder and executive director of her own nonprofit, “The Naked Truth AIDS Project”, which raises funds for AIDS prevention education programs in the USA as well as Africa.

Nick Cater

Contributing Editor

Nick Cater is a UK-based international writer and editor. A former Fleet Street journalist, he has reported from more than 40 countries so far on stories as diverse as war in Africa, environmental risks in Latin America, disasters in Europe, and the Asian sport of elephant polo.

Luke Norman

Senior Editor

Luke Norman is an experienced journalist and corporate social responsibility consultant. Having started at The Daily Telegraph, Luke has worked for a wide range of international media outlets before moving into the heady world of multi-national corporations and their sustainability commitments. Luke has transplanted himself and his family from London to Rio de Janeiro, where the views he now observes are deliriously engaging.

Doug White

Senior Editor

Doug White, a long-time leader in the nation's philanthropic community, is an author, professor, and an advisor to nonprofit organizations and philanthropists. He is the director of Columbia University's Master of Science in Fundraising Management program. He also teaches board governance, ethics and fundraising. His most recent book, “Abusing Donor Intent,” chronicles the historic lawsuit brought against Princeton University by the children of Charles and Marie Robertson, the couple who donated $35 million in 1961 to endow the graduate program at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Kent Allen

Journalist

Kent Allen is a longtime daily journalist and freelance writer. Over the past 20 years, while also writing about philanthropy and nonprofits, he has worked as an editor at The Washington Post, U.S. News & World Report and Congressional Quarterly. At present, Kent is a journalism and history teacher at The Field School, a middle and high school in Washington, D.C.

Lucy Bernholz

Journalist

Lucy Bernholz is a blogger and self-proclaimed “philanthropy wonk”. Her blog, Philanthropy 2173: The future of good, has been named a “best blog” by Fast Company and a “philanthropy game changer” by the Huffington Post.

Kim Breslin

Actor

Kim Breslin is an actress, comedienne, director, producer, artist, and chef. She has been an educator in North Philadelphia for 17 Years. Mother of two incredible children, she lives with her highly supportive cat, The Amazing Sid.

Cheryl Chapman

Journalist

Cheryl Chapman actively promotes philanthropy in the UK and globally via her journalism. She was the editor of Philanthopy UK: Inspiring Giving and now heads City Philanthropy, London, as its Director.

Stephen Dunn

Poet

Stephen Dunn, Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, is the author of 11 collections of poems, including “Different Hours,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 2001.

Regan Good

Poet

Regan Good is a freelance writer and poet living in Brooklyn, New York. She has written for The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times Magazine and others. She is currently at work on a memoir about growing up in a family of writers.

Sharilyn Hale

Journalist

Sharilyn Hale, M.A., CFRE is Founder and Principal of Watermark Philanthropic Advising where she offers strategies for meaningful giving, receiving and leading. A practitioner, author and educator, she brings a global perspective on philanthropy having served the nonprofit sector across North America, Bermuda and the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. She holds a graduate degree in Philanthropy & Development and is past Chair of CFRE International, the global certification for professional fundraisers setting standards for ethical and accountable practices.

Crystal Hayling

Journalist

Believer in a better world. Uppity advocate for social change. Former philanthrapoid. Crystal lives in Singapore where she helps donors develop strategy for effective grantmaking. She serves on numerous boards, and is a speaker and writer on civil society. Twitter: chayling

Holly Howe

Journalist

Holly Howe is a strategic communications consultant with a particular focus on the arts. She works as a freelance journalist, writing for various publications including FAD, RWD, House (published by the Soho House group) and the Irish Examiner. She also runs the Culture Vultures, a networking group for people in media and the arts. She can be found tweeting at @ hollytorious and in her occasional spare moments, she posts on her blog www.postcardsfromholly.blogspot.com

Wangsheng Li

Journalist

Wangsheng Li is president of ZeShan Foundation (Hong Kong) and a Senior Fellow of the Synergos Institute (New York City).

Lisa Macdonald

Journalist

Lisa MacDonald is a freelance writer and editor based in Toronto. A passion for philanthropy drives her involvement in initiatives that bring information and innovative ideas to Canada’s nonprofit sector leaders. Tweet her at @lisalmacdonald.

Andrew MacLarty

Actor

Andrew MacLarty is a New York based actor who has appeared on Boardwalk Empire and White Collar. Non-profit work includes narration for Partnership for a Drug-Free America, performances at the United Nations for Hurricane Katrina relief benefit shows, and Barefoot Theater Company’s ROCKAWAY benefit for Hurricane Sandy victims.

Bruce Makous

Journalist

Bruce Makous, ChFC, CAP, CFRE, has been a professional fundraiser for over twenty-seven years, with leadership positions in major educational, healthcare, and arts organizations. In 2009, he was named by the Nonprofit Times one of the “Most Influential and Effective” fundraisers in the US.

Peter D. Michael

Actor

For over 20 years, Peter D. Michael has been an established actor, voiceover talent and stand-up comedian. He is also an Emmy award winner.

Suzanne Reisman

Journalist

Suzanne is a U.S. international private client lawyer based in London. Suzanne assists philanthropists, their foundations, and international charities with cross-border philanthropy.

Julie Shafer

Journalist

Founder of Julie Shafer Development + Philanthropy, a national philanthropy consulting firm. Ms. Shafer offers a multifaceted skill set honed throughout 20 years as a philanthropy executive bringing a translational approach that bridges the gaps between philanthropists and non-profits.

Jade Shames

Playwright

Jade Shames is an award-winning writer living in Brooklyn, NY. His work can be found in The Best American Poetry blog, The LA Weekly, HOW art and literary journal, and more. He was awarded a creative writing scholarship to attend The New School where he received his MFA.

Amy Singer

Journalist

Amy Singer teaches Ottoman and Turkish history, as well as courses on Islamic philanthropy and the history of charity in the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University. Her recent publications include the book "Charity in Islamic Societies", and in 2008 she was awarded the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Award.

Sharit Tarabay

Artist

Sharit Tarabay painted the portrait of Gerry Lenfest. He is a painter and illustrator living in Montreal. He has his works published in magazines and books around the world.

James V. Toscano

Journalist

Jim Toscano is a principal in the consulting firm, Toscano Advisors, LLC, and an adjunct professor at the School of Business, Hamline University. Recently retired as president of the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, the cardiovascular research and education center of Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, he is a past chair of the Minnesota Charities Review Council and board member of Minnesota Council of Nonprofits.

Susan Yu

Journalist

Susan Yu is a journalist from the San Francisco Bay Area. She is an award-winning news reporter who was formerly based in Hong Kong for 14 years covering stories in Asia for international news media organisations. She is currently based in the United Kingdom where she freelances as a writer, editor and documentary film producer.

Chateau Charly

By Doug White

Bed, breakfast and a bridge to development in Haiti and Sri Lanka, this social enterprise is giving its guests the power to give back.

Stay in a hotel—rather, a chateau—and help charity at the same time? Yes. No, it’s not a come-on scheme where a “portion of the proceeds,” which usually means something minuscule relative to the overall take, is advertised to be donated to a cause organization that may or may not be made known to you. This is different.

It’s Chateau Charly, located on the outskirts of Charly, France and run as a nonprofit (or, "association," as they are known in that country). It sends along a full 50 percent of what it takes in for room rentals to one of two charities.

Sarah Griffiths, the founder of both charities—Bridge2SriLanka, set in motion after the Asian tsunami in 2004, and Bridge2Haiti, launched after the Haitian earthquake in 2010—was traveling with a friend after the earthquake. The friend, Paul Solomons, a wealthy businessman, took her on a visit to Chateau Charly, at the time a run-down, 32-acre mess of a place. When he said he was thinking of buying it and asked for her help in the renovation, she promptly declined, her hands full with fundraising for both countries and their respective disasters.

That’s when he confessed that the idea would be to operate Chateau Charly as a nonprofit extravagance, a vehicle to channel proceeds directly to Griffiths’ already established philanthropic goals.

She agreed, and has helped the manor become a tight ship of charitable destination ever since.

Miuccia Prada

By Holly Howe

From the runway to her eponymous foundation, the designer brings her intellectual bent to everything she touches.

With a fortune estimated at roughly $11 billion, Miuccia Prada, 65, isn’t the world’s wealthiest philanthropist, but she is arguably the best dressed. Having inherited a family haute couture manufacturer, which began in 1913 with a small leather goods store opened by her grandfather, she has grown the company into a fashion powerhouse, extending the Prada brand by expanding into men’s wear, less expensive women’s wear, shoes and fragrances, and opening some 250 Prada stores, according to Forbes. Along the way, Prada has become synonymous with understated, classic chic.

But Miuccia, who has a PhD in political science and is a onetime member of the Communist party—a so-called “aristocommunist” who demonstrated in Courreges rather than jeans—is not your average designer. With her husband Patrizio Bertelli, she has emerged as a modern-day Medici, taking a leading role in sponsoring and collecting avant-garde art. In 1993, the couple established PradaMilanoArte, opening a space in Milan for contemporary sculpture. Two years later they renamed their nonprofit Fondazione Prada and expanded its capacity to include more contemporary art, photography, film, design, and architecture. That same year they hired curator Germano Celant to work at the foundation. It was a provocative choice: Celant is famous for his ideological commitment to arte povera—literally “poor art,” revolutionary works that attack the corporate mentality through unconventional materials and style.

Fondazione Prada, Venice

Fondazione Prada, Venice

Over the next couple of decades, the Fondazione Prada gallery in Milan hosted some two dozen exhibits by established and emerging artists, commissioned new video work, published over 30 books on art and architecture, funded film festivals and international touring exhibitions, and underwrote projects changing the traditional face of Milan, such as the permanent lighting installation by Dan Flavin at the church of Santa Maria Annunciata. It funded the Fondazione Prada Chair for Aesthetics at the University of Vita-Salute San Raffaele in Milan, as well as philosophy conferences that underscore Prada’s intellectual bent. Not all Milanese have embraced her vision. “Culture is absolutely not seen as a priority,” she told The Art Newspaper in 2009. “We wanted to give a work by Charles Ray to the city of Milan, but ten years later they still haven’t found a square in which to put it.”

True to her interest in art and architecture, Prada hired Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas to design her edgy stores. She also commissioned Koolhaas’ firm to design the so-called Prada Transformer—a tetrahedron-shaped structure in Seoul that appears to shift shapes as cranes rotate the building—and a pop-up structure in Paris that served as museum, disco, and gallery space over the course of 24 hours. A more permanent home for art is Ca’ Corner della Regina, an historic Venetian palazzo the foundation took over in 2011 to hold international art exhibitions.

"Synchro System" by Carsten Höller"

"Synchro System" by Carsten Höller"

In 2015 Fondazione Prada will host events during the Milan Expo, an undertaking dedicated to food safety, security, and quality that will promote Italy as well as global issues. That may be a good fit for the designer. In 2011 Miuccia Prada told WWD that she “probably” would seriously consider a career in politics. “Politics have always been a little of my passion,” she said. “And now I [could] use my work as a tool to do things other than fashion.”

The Russian Paradox

By Luke Norman and Nick Cater

Russian oligarchs not only face a moral responsibility to give back, their evergreen President makes sure they’re doing their bit.

One collects Fabergé eggs, another acquires supermodels, and a few more invest in football and basketball teams. But whatever their avocations, Russia’s oligarchs have two things in common; their wealth is unimaginably vast and their ties to President Vladimir Putin are undeniably strong.

This situation has produced what could be called the Russian paradox. The advent of a free-market economy has led to an explosion in private wealth and according to Forbes, Moscow is home to 84 billionaires worth a total of $360 billion—and with that an unprecedented boom in philanthropy. But, increasingly, under Putin’s guidance, the philanthropy of these new tycoons resembles nothing so much as an extension of the national government.

Viktor Vekselberg

Viktor VekselbergThe roll call of Russia’s philanthropists is, predictably, a Who’s Who of the country’s most affluent and successful: Alisher Usmanov (possibly the richest man in Russia), Roman Abramovich, Vladimir Potanin (who in 2013 became the first—and, so far, only—Russian billionaire to sign the Giving Pledge), Dmitri Zimin, Mikhail Prokhorov, Mikhail Fridman, and the husband-and-wife teams of Dmitri Zelenin and Alla Zelenina, and Viktor Vekselberg and Marina Dobrynina. (It was Vekselberg who spent more than $100 million in 2004 to triumphantly return the 194-piece Forbes Fabergé jewellery collection, including nine exquisite eggs, to Russia.)

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Mikhail KhodorkovskyNoticeably absent from the list are two prominent critics of Putin: Mikhail Khodorkovsky, formerly the richest Russian, now living in Europe, and the late Boris Berezovsky, both of whom could legitimately claim to be forefathers of modern Russian philanthropy.

The pattern is clear. If you garnered vast wealth thanks to the break-up of state-owned assets in the 1990s, then you owe, big time. Campaigning in 2012, Putin frequently noted that he was considering a special tax on entrepreneurs who had benefited from acquiring state assets at “unfair prices.” Whether he does this or not (it seems unlikely), he clearly remembers his debtors. And he has not been shy about collecting.

From dropping tycoons into the governorships of obscure, dilapidated regions to strong-arming cash donations for projects of international resonance, the former KGB chief maneuvers some of Russia’s private wealth to the places he sees fit. Subtly and not so subtly (Khodorkovsky, after all, served ten years in a Russian prison for fraud and tax evasion before being released in 2013), the once-and-seemingly forever President has made it clear that, in return for their continued economic and even personal freedom, Russia’s capitalists must pay.

By all accounts, they paid handsomely to fund last year’s Sochi Winter Olympic Games, reportedly the most expensive Olympics ever, with an estimated price tag of $50 billion. A major infrastructure program has been announced for the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia, and it’s certain that it will generate both lucrative contracts and donations from grateful businessmen.

Such donations add up. In 1998 individual giving in Russia amounted to a piddling $200,000. From 2010-12, 10 of Russia’s 15 richest gave away $1.3 billion, according to Bloomberg Markets. It is an astonishing amount but there’s lots more where that came from: The combined wealth of the 10 stood at $127 billion, as of April 2013.

When compared to the West’s big donors, the figures appear a little less impressive. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, backed by Warren Buffett, gave away $6 billion of the trio’s combined $124 billion wealth in 2011 alone. However, Americans have had more time to perfect the nuanced art of modern philanthropy. What’s more, such lists fail to acknowledge the regional development underwritten by Russia’s oligarchs.

Roman Abramovich

Roman AbramovichFor example, Roman Abramovich reportedly gave $310 million to charity in 2010-12, but that doesn’t include the $164 million that Evraz, a steelmaker Abramovich owns in part, spent on social projects in its operations area in the same period. Similarly, Mettalloinvest, which Usmanov controls, gave $260 million to local services and social programs in 2010-12, on top of $247 million in personal donations.

Public office is a favourite tool of Putin’s. Fridman, Abramovich, and Zelenin have all taken a turn in the last 15 years, and it isn’t cheap. Abramovich is reported to have given or invested $2.5 billion in local services and charitable initiatives in the remote Russian Far East region of Chukotka, where he was Governor for eight years. Chukotka seems to have benefited. From 2000, Abramovich’s first year in office, to 2006 average salaries rose in the region from $165/month to $826/month. Housing and healthcare also improved with Chukotka boasting the highest healthy birth rates in Russia during Abramovich’s tenure.

Putin tweaked the rules in 2005 to facilitate this kind of appointment and now has personal responsibility for the hiring and firing of the governors for all 83 regions. As a result, when Abramovich made noises that he’d had enough of the cold of Chukotka after one term, Putin insisted otherwise. Although Abramovich was finally allowed to resign in 2008, his gift keeps giving: In 2010-12 he gave $98 million to the Territoria and Pole of Hope foundations, which support humanitarian work in Chukotka. And even several years after Zelenin left the governorship of Tvor Oblast, his wife raised more than $300,000 per year for their “A Kind Start” charity.

This type of state-directed philanthropy has elements of the old Russia. For centuries under the czars, charity was linked to the church and the largesse of the more enlightened aristocracy. The 1800s saw the rise of individual philanthropists like Baron Horace Gunzburg, and wealthy families such as the Morozovs and Mamentovs, who supported orphanages, hospitals, museums, and the arts. The Bolsheviks halted giving when they took power in 1917, and for more than seven decades philanthropy was banned. Soviet control enforced donations to officially selected charities and required millions to “volunteer” their time.

But with perestroika, new private enterprises were born, and they immediately began making donations to charity. By 1998, more than 75% of Russian companies were engaged in corporate philanthropy, although the giving was concentrated among the biggest companies. Even in 2004, more than half of Russian philanthropy came from just 20 corporations. Money went to fund the Olympic team, student exchanges and, under new accounting standards, certain business costs inherited from the Soviet era, such as staff housing. Lukoil, for example, made charitable contributions to train oil-industry recruits as well as to support young children, old soldiers and disaster victims, religious groups, and cultural endeavors.

Vladimir Potanin

Vladimir PotaninVirtually all giving was by companies, rather than individuals, until 2000, when Potanin (who later invested in the Ford Modeling Agency in the US) launched Russia’s first private foundation. (Not until 2011 were individual charitable donations finally made tax deductible.) A year later Khodorkovsky established the Open Russia Foundation, with Lord Jacob Rothschild and Henry Kissinger among its trustees, and with the goal of fostering a democratic society with activist citizens demanding a functioning state, an accountable government, and transparent human rights.

Before he was arrested in 2003, Khodorkovsky observed that his country had squeezed the progress of generations of the Rockefellers and Morgans, from robber barons to philanthropists, into just five years. Khodorkovsky himself was an exemplar of such rapid progress. Once a Communist Youth League activist, he did well in commodities and banking in the early 1990s. Subsequently, he bought cheap privatization shares and in 1995 gained control of the state oil giant Yukos for $350 million, a fraction of its market value. It became the world’s fourth largest oil company, with a one-time net worth of $15.2 billion. Until prison cut short nearly all of his activities, Khodorkovsky was putting $200 million a year into Open Russia.

As Khodorkovsky’s dramatic trajectory suggests, sizable forward movement in Russian civil society is often followed by an equally sizeable retreat. In 2012, Putin demanded that all Russian institutions receiving financing from foreign sources be registered as “foreign agents,” a regulation that crippled many of the NGOs operating there, increasing the need for Russian philanthropists to step up to the plate. Now sanctions imposed by the West in response to conflict in Ukraine are starting to take their economic toll. How this will play out for Russia’s oligarchs and their newfound philanthropy remains to be seen.

Haldun Tashman

By Sandra Salmans

Exporting the community foundation model, entrepreneur Haldun Tashman is connecting the Turkish diaspora through interest-based giving.

When Haldun Tashman, a Turkish-born entrepreneur living in Arizona, hears about another successful Turkish-American like himself, he feels more than a glow of kinship, he makes a note. Tashman, 69, is the founding chairman of Turkish Philanthropies Fund (TPF), a New York-headquartered community foundation that seeks to recruit potential donors in the U.S. and connect them to social projects, primarily in Turkey.

Tashman established TPF almost nine years ago, when the sale of a medical supplies business he’d built in Phoenix allowed him to pursue his passion. Having earned an MBA at Columbia as a Fulbright Foreign Student Fellow in 1968, in 2003 he created the Tashman Fellows program, which provides support for young Turkish or Turkish-American MBA students. But he wanted to do more, and his experience as a trustee of Arizona Community Foundation showed him how. He commissioned one of his bright young Tashman MBAs to conduct a feasibility study and, encouraged by the results and the examples of funds established by the diaspora of many other countries, formed TPF, to promote philanthropy among Turkish- Americans. At the same time, he and his wife, Nihal, established the first community foundation of Turkey in his hometown, Bolu.

In the years since Tashman and his three partners founded TPF, it has raised more than $16 million, of which it has distributed more than $11 million in grants. Most of the funds go to education, much of it specifically to gender equality programs designed to educate and empower women and girls. Like all community funds, TPF offers advantages to philanthropists who choose that route: it screens nonprofits to advise donors about where to make the best social investments; follows up to ensure the funds have been properly used; and handles the onerous paperwork that can defeat the most committed philanthropist; to do this, Tashman travels in a continual loop between Phoenix, New York, and Istanbul.

TPF money has gone to build village schools, provide disaster relief after the earthquake in eastern Turkey in 2010, and support traditional rugmaking in Anatolia. One donor in New York, rather than throwing a birthday party for her daughter, raised $20,000 to buy books for girls in Turkey, Tashman notes. In Bolu, the Tashmans are using their own community foundation to support the development of an infrastructure for philanthropy, as well as an early-education project. “There are foundations in Turkey, but everybody wants to do their own thing,” says Tashman, who hopes to bring people together to share best practices and give more strategically.

But to thrive, he notes, TPF must recruit the next generation of Turkish-Americans. TPF has a junior board of younger directors, U.S.-educated professionals with dazzling credentials. One of the Tashmans’ daughters is a donor to TPF, and Tashman believes he is providing seed capital through his fellowships. By the time the fellowship program wraps up, he estimates, it will have sent 50 fellows out into the world. “I’m looking for one or two who will be very successful and will do great things in philanthropy,” Tashman says, “and I’ll feel, mission accomplished.”

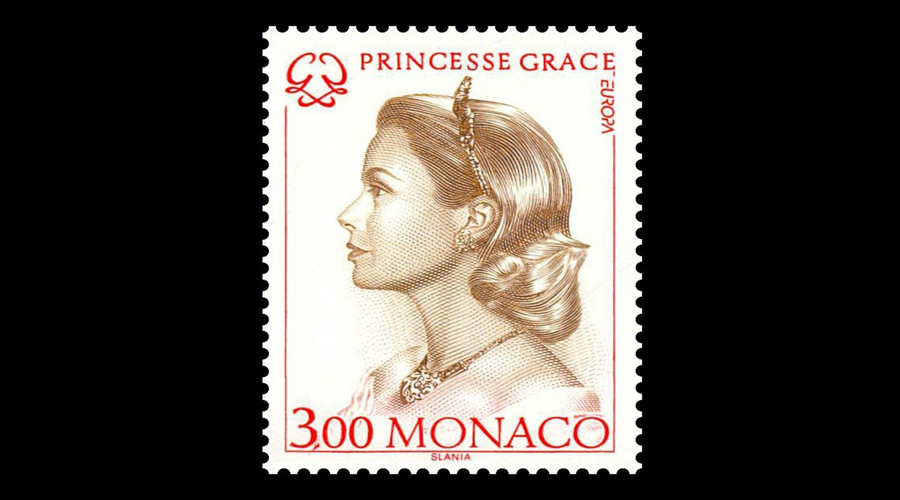

Princess Grace Foundation

By Bruce Makous

Originally created to salve Monaco's royal family's grief, the Princess Grace foundation celebrates three decades assisting emerging talent in theater, dance, and film.

She was the ultimate fairytale heroine, a radiantly beautiful commoner who’d caught the eye of and later married a prince. So when Princess Grace met an early death in a car crash in 1982, at the age of 52, it was fitting that her bereaved husband, Prince Rainier III, would create a foundation in her own country to foster and celebrate the arts.

The Princess Grace Foundation-USA focuses on the Princess’s primary philanthropic interests—discovering and assisting emerging artists in theatre, dance, and film. The foundation, a publicly supported not-for-profit headquartered in New York City, provides contributions to artists who are beginning their careers, primarily in the form of scholarships, fellowships and apprenticeships. To fund the foundation, the Prince mobilized Grace’s supporters, which included the likes of Frank Sinatra and Cary Grant. (The foundation is distinct from the Princess Grace of Monaco Foundation, which the princess created shortly after her marriage to encourage local artists and crafts people.)

Through its flagship program, the Princess Grace Awards, the Princess Grace Foundation-USA provides the financial assistance and moral encouragement needed by emerging artists so that they can focus on the creative process. Applicants must be nominated by nonprofit arts organizations, and a panel composed of distinguished professionals in theatre, dance, and film annually selects the winners on a competitive basis. Since the Foundation’s inception, more than 750 Princess Grace Awards totaling nearly $10 million have been given to performing artists. Many winners have subsequently achieved public recognition and critical acclaim, including Oscars, Tonys, Emmys, and other awards.

Among the notable winners are Robert Battle, the dancer and choreographer who now serves as Artistic Director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater; Yareli Arizmendi, the Mexican actress who played Rosaura in Like Water for Chocolate; Bridget Carpenter, playwright and screenwriter nominated three times for Best Dramatic Series by the Writers Guild of America for her work on Friday Night Lights; and Stephen McDannell Hillenburg, the animator, writer, producer, actor and director best known for creating the SpongeBob SquarePants TV series.

Those Princess Grace Award-winners who subsequently distinguish themselves in theater, dance, or film receive an additional form of recognition—the Princess Grace Statue Award. To date, 54 artists have received this award. A third type of recognition, the Prince Rainier III Award, established in 2005 after the Prince’s death, is presented to eminent artists who have also made significant humanitarian contributions. This award, which includes a grant to the philanthropic organization of the honoree’s choice, has been given to such stars as Julie Andrews, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Twyla Tharp, Denzel and Pauletta Washington, George Lucas, and Glenn Close.

Her family is carrying on her philanthropic legacy. Prince Albert II is the vice chairman of the foundation, and Princess Caroline is president of AMADE Mondiale, the Monaco-based NGO that Grace founded during her lifetime to help children in the developing world. Recently, for example, AMADE has provided support to Syrian children in refugee camps and to families devastated by the typhoon in the Philippines.

In fairytales, the royal couple lives happily ever after. But even when death intervenes, it seems, they can make others’ dreams come true.

The Community Foundation

By Sandra Salmans

How a hundred-year-old idea is reshaping philanthropy around the world.

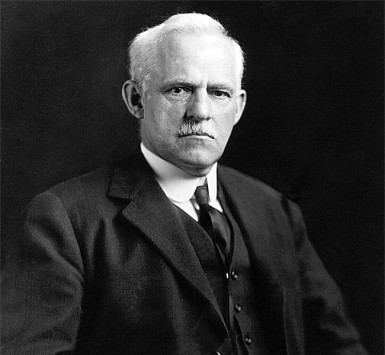

Carnegie and Rockefeller had recently established—and lavishly endowed—their eponymous foundations when Frederick Goff, president of the Cleveland Trust Company, had a different idea: a “community trust” to which the city’s philanthropists could all contribute. Interest on the money, it was declared, would fund “such charitable purposes as will best make for the mental, moral, and physical improvement of the inhabitants of Cleveland.”

Frederick-Goff

Frederick-GoffThus, 100 years ago, was born the world’s first community foundation. (Bequests were, not coincidentally, deposited at the Cleveland Trust Company—setting a precedent for the charitable funds later established by financial services companies such as Fidelity, Schwab and Vanguard.) The Cleveland Foundation was soon leaving its mark on the city, supporting the creation of the so-called “emerald necklace” of the city’s parks, shaking up the corrupt judicial system, spearheading public school reforms that included equal education opportunities for girls. And within five years, community foundations (CFs) had sprung up in Chicago, Boston, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Buffalo, NY.

The growth of CFs since then has been immense, immeasurably greater than even the visionary Goff could have dreamed. Today there are an estimated 700 CFs in the US. According to CF Insights, a consultancy specializing in community foundations, assets at CFs in the U.S. totaled $66 billion in 2013, an increase of $8 billion over the previous year. The Silicon Valley Community Foundation (SVCF) led the way, at $4.7 billion, followed by the Tulsa Community Foundation, with $3.9 billion, and the New York Community Trust, with $2.4 billion. (SVCF’s assets, which ballooned with a $1 billion gift from Mark Zuckerberg in 2013, surged ahead again in 2014 with a $500 million stake in the camera maker GoPro from its founders.)

Mark Zuckerberg

Mark ZuckerbergIn 2013, commemorating the 100 years since the first CF was established, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation created a chair on community foundations at Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. And this past October, to celebrate the centenary of the CF, the Council on Foundations gathered leading philanthropic organizations in Cleveland, where it all began.

What’s more, the rest of the world—including the developing world—is rapidly following America’s lead. According to the latest tally by WINGS (Worldwide Initiatives for Grantmaker Support), a global network of grantmaker support organizations, and the Community Fund Atlas, which is underwritten by the Cleveland Foundation, there are currently some 1,100 CFs outside the US, in more than 50 countries and on six continents. Having launched in the US and Canada in 1914, the CF crossed the Atlantic to Britain about 35 years ago, took root in Germany around the time of reunification, spread to Russia and the former Soviet states, and is currently establishing a foothold throughout the developing world. Between 2010 and 2014, eight new CFs were established in Asia-Pacific, four in sub-Saharan Africa, four in Latin America and two in the Middle East. As the Mott Foundation aptly declared in its 2012 annual report, CFs are “rooted locally, growing globally.”

Whether in the industrialized world or the emerging one, CFs are identical in one key respect: They are public charities that tap the wealth of their communities, with the goal of redistributing it locally. That mission has universal application, asserts Emmett Carson, who is the SVCF’s chief executive officer and is also the visiting holder of the new Mott chair on community foundations. “We should think of the community foundation concept like water,” he says. “The water is the same, but it takes on the shape of whatever community you pour it into.”

Emmett Carson

Emmett CarsonAnd the fact is that CFs differ markedly from one country to another—and, increasingly, even within a country. In the developed world, many CFs are taking on a more activist role than in the past, initiating projects and partnerships as well as donating to established programs. What’s more, many are traveling far beyond their borders, accepting funds from a wider audience and playing a role on the national and even international stage

Meanwhile, the CFs that are springing up in less developed areas—Africa, Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe—are digging deep into their communities to convince residents to trust the very concept of pooling and distributing funds. While endowments and professional leadership are the hallmarks of long-standing CFs in the US, money necessarily takes a back seat to other priorities among CFs in emerging countries, where there are only small pockets of wealth. “They have to prove they’re relevant to the community and need to establish trust where often there are low levels of trust,” notes Nick Deychakiwsky, program officer for the Mott Foundation’s civil society team. In fact, in many cases those CFs have received a jumpstart by foundations such as Mott, Ford, Open Society and Aga Khan, and also appeal to the diaspora for funds.

Nick Deychakiwsky

Nick DeychakiwskyAs Jenny Hodgson, director of the South Africa-based Global Fund for Community Foundations, observes, community philanthropy is as old as, well, communities themselves. “Every country and culture has its traditions of giving and mutual support between family, friends and neighbors,” she has written, pointing to the tradition of burial societies across Africa and hometown associations in Mexico.

However, the new generation of community philanthropy institutions—fueled by factors ranging from a growing concentration of wealth to the popularity of social media, according to WINGS executive director Helena Monteiro—take a more strategic approach to giving. “Most are about development rather than donor services, and they do a lot of capacity building,” Hodgson told Giving. “They’re building civil society, essentially.” As the Kenya Community Development Foundation, a CF established in 1997, asserts on its website, its goal is “the growth and sustainability of communities by their strong engagement in owning and driving their development efforts.” (Italics are KCDF’s.)

Helena Monteiro

Helena MonteiroA sampling of this new breed of CFs offers a glimpse of the variety of programs being undertaken:

- In Egypt, the Community Foundation for South Sinai is working to support the Bedouin, who have long been marginalized. The CF is working on several fronts to raise the tribes out of poverty and preserve their heritage; projects have included teaching the women how to make useful wool products, and providing a camel to a boy who was his family’s breadwinner.

- In Costa Rica, the Monteverde Community Fund, initially founded to invest tourism revenue in preserving the rain forests, has added a social portfolio. Among other projects, it is promoting a community Internet-based radio station, training local youth to create programming and encouraging them to engage in public discourse.

- In Romania, multiple CFs have organized annual “swimathons” to raise their profiles, garner funds and spread the ethos of sharing. In Cluj, the country’s second most populous city, revenue went to support new programs for young people, including a robotics class in an elementary school and education for students with special needs.

- On the West Bank, the Dalia Association, a Palestinian CF, gave women from nearby villages $6,000 to build a park. The women went on to secure additional donations, including the land, utility hookups, a basketball court, a playground and a library.

- In Slovakia, the Banska Bystrica City Foundation—Eastern Europe’s oldest CF, initially launched as a World Health Organization project—has assembled a group of local donors that assist the city’s street children, provide support for the local Roma community, and encourage younger people to take an interest in philanthropy.

While all these CFs have struggled to raise money, elsewhere they have also encountered tight governmental controls or opposition. Even there, however, they are making headway. According to a recent report by CAF (Charities Aid Foundation) Russia, a support group for charitable and nonprofit groups, nearly two-thirds of the membership of CF governing boards comes from the authorities and business; even so, starting with one CF in 1998, Russia today has more than 45 community foundations. The situation is more problematic in China, where very few private organizations are permitted to do fundraising, grantmaking is relatively unknown and civil society is weak. Still, says Hodgson, “everybody is talking about community foundations in China. There’s lots of energy right now.”

That’s also an apt description of the situation in the US, where the biggest CFs are stepping up their game. Rather than limiting themselves to making grants to established programs, “community foundations are increasingly moving into the sphere of brokers for community solutions,” declares Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker, who heads the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo in New York State. Dedecker’s group was the prime mover in launching Say Yes to Education, an initiative that has brought together school parents, union leaders, the business sector and other stakeholders to provide year-round support to students K-12, including college scholarships.

Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker

Clotilde Perez-Bode DedeckerArguably the most striking example of the supercharged CF is the Silicon Valley Community Foundation. The result of a merger of two leading CFs in 2006, SVCF is not only the largest single grantmaker to Bay Area nonprofits, it’s the fifteenth largest international grantmaker in the United States, according to Carson. Furthermore, while SVCF draws much of its wealth from the affluent high-tech community, it also has donors who neither live in the Bay Area nor give to it, but choose to use SVCF as the means to distribute their philanthropy.

To Carson and others, these developments represent a natural progression for CFs in a society that is ever more global. “People increasingly see themselves as national citizens and, more likely, as global citizens,” he notes.” And because many Americans, or at least their parents, hail from different countries, they want to be able to send money overseas as well as to contribute to their new homelands. To compete in this arena—and also to counter the inroads made by financial services companies such as Vanguard and Fidelity, which are vying for donor-advised funds—the leading community foundations are carving out a niche in international philanthropy.

To some people in the CF world, venturing so far afield seems incompatible with the very notion of a community foundation. “A part of me says, ‘Shouldn’t it all be local?’” says the Mott’s Nick Deychakiwsky. But as someone with his own strong spiritual ties to Ukraine, Deychakiwsky concedes that “we’re all living in a more globalized world.” Ultimately, he hopes, globalization will lead to US-based CFs becoming more involved with community foundations abroad—relationships that could benefit organizations in both the developed and developing world. (And there are surprising similarities: Experts notes that CFs in emerging countries have a lot in common with those in rural areas of the US such as the deep South, where “hyperlocal” community development remains the sole focus.) “It’s amazing how much is transferable,” agrees Dedecker of the Community Foundation of Greater Buffalo, who is exploring the sharing of best practices with a CF in Nottingham, England. “The universal drive is for significant change and a strong sense of place,” she concludes. “That’s what unites us all.”

The Persistence of Philanthropy

By Amy Singer

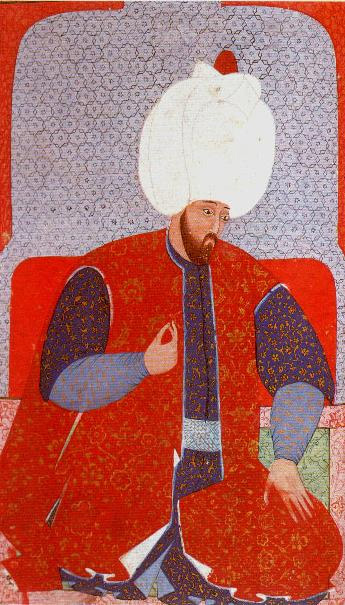

One of the most profound Ottoman legacies to modern Turkey is a long history of private philanthropy.

I fell into the study of philanthropy while trying to make sense of rural taxation and land tenure in 16th century Palestine, then under Ottoman rule. Several weeks in the imperial archives of the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul brought me face-to-face with an exquisite series of long scrolls penned in gold, lapis, and black inks some five hundred years old. They recorded orders from Sultan Süleyman “the Magnificent” to transfer properties to his wife, Hurrem Sultan. From these she immediately created an endowment, a waqf, to support a public utility in the middle of Jerusalem, a space allocated for what we may now consider a soup kitchen, serving meals twice a day.

Ottoman sultans, and in fact Muslim rulers and their families since early Islamic times, made large endowments to support schools, mosques, roads, hospitals, baths, bridges, cemeteries, as well as the odd idiosyncratic fund to care for cats or feed birds in the winter. Founding public works was part of their job description, a function sandwiched between religious leader and politician. Meanwhile, individuals with any means often made their own endowments of every possible size, funding public welfare and their own families in the process. This type of giving is a common encouragement throughout the Qur’an as well as the Old and New Testaments.

The specific Ottoman cases also raise more universal questions about philanthropic giving. How voluntary is voluntary? Why do some gifts earn praise and others a shrug? What does practical altruism mean and does it really exist? Where do the boundaries lie between individual initiative and government responsibility? Who decides which people deserve to benefit from philanthropy (like who gets to eat at a public kitchen)? These types of questions offer insights from the past to today’s philanthropists, who in the very nature of their work look to the future.

Historians examine the past to understand how people functioned in societies and cultures in times preceding our own. We try to understand what people valued in the past, what worried them, how they coped with threats, what they celebrated and why, and what precipitated changes in their lives. We ask questions about how people did what we still do: make a living; pray; raise children; build; ail and heal; fight wars; trade. These constants link humans across space and time through experiences that are at the same time very similar and utterly distinct.

Philanthropy—voluntary giving of material wealth, time, and expertise for the benefit of individuals or communities—is one of those constants, persistently present. It is for this reason that a column written by an historian just might be of interest to an audience of contemporary philanthropists and philanthropic professionals. History not only enriches our lives by explaining how change comes about in the world but it connects us to people who participated in those changes. Our own world is more dynamic, complex, beautiful, and simply bigger when we understand more about someone else’s.

What Women Want

By Kecia Barkawi

When I started VALUEworks, a Zurich-based multi-family office, over ten years ago, two concepts were still rather nascent in the wealth management industry: philanthropic advisory as a service and women as a market. Back then, it was not the norm to put philanthropy at the forefront of wealth and family estate planning as it was a consideration usually reserved for retirement, old age, or even death. At that time, women were also not viewed as the most desired clients and more frequently were considered wives or daughters who married into or inherited wealth with little financial knowledge, let alone decision-making power, of their own.

Much has changed since then. Philanthropy has now become a valuable component of family governance and multi-generational planning for wealthy families. Moreover, the tide for women has shifted. In the US, it is believed women will own two-thirds of wealth in the next decade, driven by generational and spousal transfers. In Asia, a new generation of women is transforming the region’s cultural legacy as more affluent, educated, and empowered women come into the picture.

Women are wielding more financial power and astuteness. The movement is real, global, and here to stay. However, the financial industry does not seem ready to serve the needs of wealthy women, even though these are more likely than men to work with advisors whom they value highly. A study on Women of Wealth by Heather R. Ettinger and Eileen M. O’Connor published in 2011 showed that women know what they want. They want to be understood and listened to—the whole story, not just the financials. They want a tailor-made approach focused on their unique needs—not a generalization about women issues, or a product. They want honesty and transparency, and a clarity of their undertakings and what the risks involved are. And philanthropy advisors, too, must fully grasp what this means.

Kecia Barkawi

Kecia BarkawiMuch has been written about gender differences in giving. Sondra Shaw-Hardy and Martha Taylor have expertly illustrated these in their 2010 book, Women and Philanthropy. In my twenty years as wealth advisor, I have come to believe that gender differences are important to keep in mind. Yet, still today, many women of wealth continue to face challenges getting customized services. They struggle to find a truly understanding advisor, because they are either patronized or treated differently on account of their gender. In competing to offer services for women, many in the industry have opted for a cosmetic shortcut. As someone once wrote, “Changing the font to pink doesn’t change the service.”

Together with my mainly female team I pursue a sincere and holistic approach that allows our valued female clients to become engaged and motivated leaders in their philanthropy, not wallflowers.

While writing this article I have reflected on what I have learned from years of philanthropy advisory, but also as founder and CEO of a multi-family office. Below is a list of five key observations which could be useful and equally applicable to any of an advisor's clients.

- Understand their journey. Women play multiple roles. They own successful businesses, but are also mothers who care for kids and manage a household. They are wives who support their spouses, and daughters who care for older parents. Where they are on their professional and personal journey matters tremendously to their philanthropic decisions. As Heather Ettinger and Eileen O’Connor highlight in their study, transition issues such as death, divorce, retirement or being caught in the so-called “sandwich generation” of caring for children and aging parents, define the needs, expectations and financial concerns of successful women. Advisors have to approach these phases in the client’s life with deep sensitivity as these roles matter a great deal. Equally important is taking in the big picture on how these roles change over time. A good advisor should think ahead of these transitions.

- Encourage leadership. While we celebrate how many women have taken the reins of the most influential philanthropies today, there are countless others who remain in the background. Being a leader isn’t easy as it means accountability for financial, operational and strategic decisions. It also implies understanding more fully the intricacies of running a foundation, or spearheading fundraising, or being the face of an advocacy. As advisor I can provide a great service by identifying the personal development needs of my female client, identifying skills or experiences that will help her fulfill her role and be proud of her philanthropic achievements.

- Address issues of risk. Women are characterized as more risk-averse and conservative when it comes to finances than men. The 2011 Study of High Net Worth Women’s Philanthropy by the Center on Philanthropy reports that nearly 40% of women are not willing to take any risks with their philanthropic investments versus just 22.8% of men. I generally believe in a conservative approach. We women are less prone to overconfidence and tend to plan more carefully for uncertainty. As an advisor faced with a highly risk-averse client, I find providing an educational path the most effective approach to ensuring she feels comfortable with her decisions. It is important to acknowledge and highlight risks and to admit that we cannot possibly know everything and investigate every scenario. Nevertheless, by bringing in experts, organizing open discussions, exchanging useful readings and creating an atmosphere of discovery, we can all learn together. The most meaningful philanthropic engagements come out of such dialogues and exploration.

- Connect them to other philanthropists. There are many successful women of wealth who are seeking to make a real difference with their philanthropy. Often they come across the same challenges and obstacles. One of the initiatives I am very proud of is a Swiss-wide network for women in philanthropy which VALUEworks initiated in 2012. By creating a highly exclusive space for women philanthropists to come together to exchange ideas and learn from each other, we can give them the keys to empowering and enriching their own giving journeys. As advisor I am really motivated by the outcome: clients and contacts are inspired, energized and truly appreciate the connections they make through the network. They become more open to sharing their views and talk about problems encountered and to partnering with others, raising their effectiveness and efficiency as givers.

- It isn’t all about gender. According to the study of Ettinger and O’Connor a big amount of dissatisfaction of women clients stems their perception that gender is the reason for poor financial advice, disrespect and condescension from the financial services industry. We need to reframe our entire approach so that it is not gender-centric which has the tendency to patronize women, alienating them even further from advisors. Successful, empowered, educated women need and deserve competent philanthropy advice, served to them with care and professionalism. Service providers are better advised to invest their time and resources in creating a tailored approach that makes their philanthropy both socially relevant and personally meaningful. And this way, we as advisors can have a greater impact, too.

If we care about excellent service to our clients - male and female - we need to keep our gender biases in check. What women truly want is to be understood and treated as equally special as every other valued client.

Ingvar Kamprad

By Doug White

The Swedish billionaire is increasing his philanthropy, but his lifestyle is as minimalist as IKEA's flat packed furniture.

There’s a good reason that IKEA is a household word while virtually nobody can name the man behind it. The Swedish company, now based in the Netherlands, was founded by multibillionaire Ingvar Kamprad, whose lifestyle is as modest as IKEA’s minimalist product design, packaging, and pricetags.

Born in 1926 in Sweden, Kamprad reportedly developed the no-frills retailing concept behind IKEA as a teenager at his uncle’s kitchen table. (IKEA is derived from its founder’s initials plus Elmtaryd, the family farm in Sweden where he was born, and the nearby village of Agunnaryd.) On a less positive note, he also flirted with fascism during World War II, an interest that he later blamed on his family’s German roots and that he has called “the greatest mistake of my life.”

In 2007, Forbes ranked Kamprad the fourth wealthiest person in the world with a net worth of $33 billion; by 2011 he’d suffered the biggest downgrade of wealth on the list, and is currently said to be worth about $3 billion. The reason for the drop? Philanthropy . . . and tax laws. Most of IKEA’s stock was transferred to a holding company and the Stichting INGKA Foundation (INGKA is derived from Kamprad’s first and last names); under the laws of the principality of Liechtenstein, where the foundation is headquartered, he cannot profit from the business. In June of 2013 Kamprad stepped down from the board, turning over control to his three sons.

Whether the foundation was established as a philanthropic vehicle, a tax dodge, or an anti-takeover device is debatable. In 2006 the Economist reported that the INGKA Foundation was the largest of its kind in the world, with assets estimated at $36 billion; it also noted that it was “one of [the] least generous.”

That might not come as a total surprise, given its legacy. Kamprad, who relocated from Sweden to Switzerland decades ago to save taxes (he has stated that he plans to return to Sweden) is famously frugal. He drives a 20-year-old Volvo, flies economy and books second-class rail, stays at inexpensive hotels, reuses his tea bags, and pilfers salt and pepper packets from restaurants. In an effort to preserve natural resources as much as pinch pennies, he also asks employees to use both sides of a piece of paper when they are writing anything down. (Among the maxims from the so-called IKEA bible which he authored: “A waste of resources is a mortal sin at IKEA.”)

To his credit, however, Kamprad is working to change the image of the foundation, which he chairs and whose stated purpose when it was established in 1982 was “to promote and support innovation in the field of architectural and interior design.” Following the Economist’s critique, he went to court for permission to give more funds to young people in the developing world. In 2011, the foundation announced plans to increase its contributions to about $135 million per year, to be divided among a refugee camp in Kenya, United Nations agencies that help children and refugees, and Save the Children.

The Anonymist

By Sandra Salmans

Once the masked marvel of anonymous giving, Chuck Feeney now preaches the gospel of “giving while living.”

At one time, Chuck Feeney would have done everything in his power to keep his name out of this article—and off this site. He was so completely committed to his brand of covert philanthropy that beneficiaries were warned that his gifts would be snatched back if they revealed the source; funds were conveyed so clandestinely that some university dons fretted they’d be suspected of receiving laundered money. Yet his contributions were so large that when, inevitably, word of his magnanimity began to leak out, many in the philanthropic community automatically assumed that every “anonymous donor” was Chuck Feeney.

And, in many cases, they were right. Although the ranks of anonymous donors are, by definition, unnumbered, Feeney has surely been among the most generous. Over the past 30 years, he has given billions of dollars through his foundation, Atlantic Philanthropies, to a wide range of causes, starting with his alma mater, Cornell University, spreading to the entire university system in Ireland—and to the peace process in Northern Ireland—and more recently encompassing large-scale projects in education, science, health care, and other areas in Vietnam, South Africa, and Australia as well as the United States. In 1997, when a business transaction finally outed him, Time declared, “Feeney’s beneficence already ranks among the grandest of any living American.”

But in the past 17 years, having been forced to shed his cloak of invisibility, Feeney has become an eloquent—if still low-key—spokesman for philanthropy, and specifically for “giving while living.” In 2011 he signed the Giving Pledge launched by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett to encourage initially only the wealthiest Americans to commit to giving the majority of their wealth to good works either during their lifetime or after their death. (Feeney chose the first option, and Atlantic Philanthropies is slated to spend down its assets and go out of business by 2016.) He has allowed the press to tag along on his visits to donees; expounded on his views in a one-hour documentary about himself; cooperated in a biography, “The Billionaire Who Wasn’t,” by Irish journalist Conor O’Clery; and accepted honorary degrees and other recognition, including induction into the Irish American Hall of Fame. He has even released previous beneficiaries from their vow of silence. “The idea of anonymous giving was good, but eventually we became synonymous with anonymous,” Feeney told O’Clery. “It became evident we were kidding ourselves.”

All this amounts to a transformation for a man whom Forbes once called “the James Bond of philanthropy.” In his biography, however, Feeney notes one constant: “I had one idea that never changed in my mind—that you should use your wealth to help people.”

Although he is a modest celebrity today, at least in philanthropic circles, Feeney is unchanged in other respects, too. He remains a deeply private person, spurning the displays of wealth he could easily afford in favor of a simpler life that includes off-the-rack suits, $15 watches, and economy-class plane tickets to visit Atlantic beneficiaries. While he thrives on competition, money, for him, is just a means of keeping score. Growing up in blue-collar New Jersey, Feeney won a scholarship to the Cornell School of Hotel Management and then—through a combination of luck, street smarts, and sheer hubris—embarked on a business selling cars, perfume, and liquor to U.S. servicemen and tourists in Europe. That experience led to the founding of Duty Free Shoppers (DFS), a chain of airport shops that, capitalizing on a surge in international tourism, were an almost immediate success. But because DFS was privately owned by Feeney and three partners, it satisfied his penchant for secrecy. One reason Feeney was able to fly under the radar for so long was that the source of his fortune—as well as its uses—went undisclosed for years. In 1984, he transferred his sizable DFS stake to Atlantic. It wasn’t until he sold Atlantic’s DFS shares to a publicly-traded company in 1997 that Feeney’s cover was blown—and, with that, his curious identity as the world’s leading anonymous donor.

Those who know Feeney—and many more who don’t—have struggled to explain his obsession with secrecy, particularly when it comes to giving. Feeney likes to recount the story about his mother, a nurse, who used to jump into her car to pick up a disabled neighbor as he struggled to walk to the bus stop, insisting that she was going his way. Some family members have suggested that he became used to operating covertly in his intelligence work during the Korean War, a pattern reinforced when he was growing DFS without stirring up the competition. Still others point out that Feeney insisted on a low profile when he and his family—which ultimately included five children—lived in Europe during the 1970s, a time when criminal and political gangs over the border in Italy frequently kidnapped wealthy children for ransom. Feeney has also said that he did not want to be besieged by requests for donations, or to discourage other contributors from giving to a worthy cause.

Then there’s the critical role played by Harvey Dale, a Harvard Law professor and founding president of Atlantic Philanthropies, whom Feeney has described as the most influential person in his life. It was Dale who introduced Feeney to the writings of Maimonides, the 12th-century Jewish philosopher who said that it was best if the giver and receiver didn’t know each other, and Dale who pointed out that anonymous giving was favored in both the Sermon on the Mount and the Koran. Dale also urged Andrew Carnegie’s essay, “Wealth,” on Feeney, who has distributed copies to family and friends. Although Feeney resisted Carnegie’s lavish lifestyle, he responded to the steel magnate’s view that the rich had an obligation to use their assets responsibly to help others.

Feeney will be 85 when Atlantic Philanthropies allocates its last grants in 2016. At that time, he can probably—and gratefully—embrace a less visible lifestyle. But his name is inscribed among the world’s great philanthropists. He is Anonymous Donor no more.

Gilbert Brownstone

By Holly Howe

The Swiss-American art collector thumbed his nose at American foreign policy with his biggest gift yet.

Gilbert Brownstone likes to say that he has a “Cuban heart.” The American-born art collector holds the country in such high esteem that in 2010 he donated 120 artworks to the National Museum of Fine Art in Havana, all channeled through his namesake foundation established in 1999.

The gift, which included works by major 20th-century artists like Andy Warhol, Marcel Duchamp, Pablo Picasso, and Joan Miró, was a significant coup for the museum. Brownstone, who personally delivered the art, was awarded the Cuban Medal of Friendship for his support.

Brownstone, who is in his early 70s and arrived in France at the age of 17 and studied at the Sorbonne, is a Swiss national but constant traveler, dividing time between the United States, Paris, and Central and South America. He worked at a contemporary art museum in Paris, the Picasso Museum in Antibes and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, and later opened his own gallery in Paris.

When that closed, he created The Brownstone Foundation in 1999 with the mission of supporting projects and establishing charities within the scope of “cultural and educational development.” Besides donations, of which the Cuban gift is one of its most spectacular, the foundation has loaned pieces of art to institutions around the world. The foundation’s beneficiaries include New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Pompidou Centre in Paris.

Gilbert Brownstone standing next to an Alexander Calder piece.

Gilbert Brownstone standing next to an Alexander Calder piece.Still, Brownstone has made the Caribbean island nation his special priority. In addition to gifts of art, he’s underwritten the creation of a 2,000-square-foot community center in the El Cotorro neighborhood of Havana (the project awaits final approval), as well as a new rehearsal space at the Havana Dance Centre; he’s supplied musical instruments to community groups; and initiated in 2002 and continues to fund the Noemi prize. Although the prize was originally intended to grant Cuban artists—dancers, musicians, and writers as much as visual artists—a three-month residency in Paris, in 2008 its scope was expanded to include artists from members of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas, a trade group which was founded by Cuba and Venezuela as an alternative to NAFTA and includes Latin American countries with socialist-leaning governments.

In fact, Brownstone’s philanthropy has carried a strong political message. When he donated art to Havana, he dedicated that gift to the so-called Five Heroes, Cuban spies imprisoned in the United States since 1998 for their alleged role in shooting down two planes piloted by an anti-Castro activist group two years earlier. In 2011, Rene Gonzalez became the first of the five to be released and returned to Cuba after serving 13 years in an American prison. Two years later, a second prisoner was released and more recently, spurred by the easing of the decades-old American trade embargo on the island, the final three of the remaining Heroes were granted release in a prisoner exchange with the U.S. in December.

Brownstone is also on the board of the Center for International Policy, a liberal group that works on issues such as U.S.-Mexican border policies, deforestation and, of course, re-establishing ties between the U.S. and Cuba. Even before the rekindling of state relations between the two countries late in 2014, Brownstone was long building his own bridge to Cuba.