About

Global Team

Roberta d’Eustachio

Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Roberta d'Eustachio (Rd'E) is an entrepreneur obsessed with delivering media from the social investor/philanthropist's point of view. That desire led to founding The American Benefactor, the first consumer magazine for philanthropists, as well as Giving Magazine and each of its subsequent evolutions: from print, to digital, to mobile with Facebook Instant Articles, delivering stories of social impact - for everyone, everywhere.

Rd'E has consulted with, and/or received investment from, leading global brands, including: The Economist, the Financial Times, Euro Money/Institutional Investor, the Pitcairn Family Office, Fidelity Capital and the World Bank as well as philanthropists and social enterprises around the world.

After serving as chief-of-staff to Dame Stephanie Shirley, the British Government’s Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy, Rd'E founded the AmbassadorsForPhilanthropy.com enterprise to give social investors a voice worldwide.

Dame Stephanie Shirley

Philanthropist & Believer-in-chief

Dame Stephanie “Steve” Shirley is a British entrepreneur turned philanthropist. She originally arrived in London as an unaccompanied Kindertransport child refugee from Austria during WWII. “Steve” was an early pioneer in technology and, after taking her company public, she has given more than $100 million to organizations that specialize in autism research and technology, including founding the Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University. Appointed by Prime Minister Gordon Brown to the title of the British Government's Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy 2009-2010, she believes in the advancement of the philanthropist voice worldwide.

Her memoir “Let It Go” was recently published, chronicling her life so far.

"Steve" is the Believer-in-chief to Giving Magazine, providing the means to imagine and execute its potential to the fullest.

Jerry Alten

Chief Curator

Jerry Alten is a world-renowned art director of magazines, across all devices, and other marketing and advertising work, winning many prizes in the media field. Under Walter Annenberg’s ownership of TV Guide, Jerry took the circulation from 5 million up to 19 million during his tenure as art director. He continued to work with Rupert Murdoch’s organization after the buy out of TV Guide and created the first interactive website for the magazine. Jerry was also the original investor in The American Benefactor Magazine and art director, which succeeded in obtaining more than $7 million worth of investment from Fidelity Investment's venture firm.

Brian Lipscomb

Chief Technologist

Brian Lipscomb has been involved with technology for over twenty years, and founded technology services company Divergex, based in Philadelphia. Specializing in all aspects of computers, Brian brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to Giving Magazine. His philosophy is: “Do it right, or don’t do it at all.”

Lipscomb adds: “Technology is a constantly evolving industry. People who use technology daily don’t have the time to study and learn all of the new and different terms and capabilities. I work to show people how technology can improve their efficiency, productivity and, ultimately, their lives.”

Jay Balfour

Managing Editor

Before Jay became the Managing Editor for Giving, he was a freelance writer and editor based in Philadelphia. With an academic background in Philosophy he leverages an informed perspective on everything from African music to youth movements in the West for several publications both online and in print. At Giving Magazine he shares a passion for unabated reporting and the ushering in of a new age in philanthropy.

Sandra Salmans

Executive Editor

Sandra Salmans is a New york-based writer and editor who works primarily in the nonprofit field. She began her career as a business and financial journalist at Newsweek and The New York Times, but has also covered national news, education and the arts. Prior to going freelance, she was a senior officer in communications for a leading foundation in Philadelphia.

Nicole Raeder

Digital Design Manager

Nicole delights in great design. That's why her commitment is compulsive; contagious even, to get it right. Or, change it. Or, change it again. Whatever is required to finding the way to the end point, which is sometimes the beginning. In other words, she never gives up, or stops, till the thing clicks.

She also loves cats.

Damon d'Eustachio

Co-Director, Global Membership

A foodie who navigated his way from the city of brotherly love to Charleston, S.C, Damon is devoted to serving nonprofits worldwide that believe the philanthropist voice must be heard.

Damon graduated from the College of Charleston in Art Administration and performed an internship at London’s prestigious Tate Gallery’s New York City office.

Jessica Lambrakos

Co-Director, Global Membership

Jessica is responsible for the management and development of the Global Awards for nonprofits of Giving Magazine for their nominated philanthropists and supporters.

She also serves as founder and executive director of her own nonprofit, “The Naked Truth AIDS Project”, which raises funds for AIDS prevention education programs in the USA as well as Africa.

Nick Cater

Contributing Editor

Nick Cater is a UK-based international writer and editor. A former Fleet Street journalist, he has reported from more than 40 countries so far on stories as diverse as war in Africa, environmental risks in Latin America, disasters in Europe, and the Asian sport of elephant polo.

Luke Norman

Senior Editor

Luke Norman is an experienced journalist and corporate social responsibility consultant. Having started at The Daily Telegraph, Luke has worked for a wide range of international media outlets before moving into the heady world of multi-national corporations and their sustainability commitments. Luke has transplanted himself and his family from London to Rio de Janeiro, where the views he now observes are deliriously engaging.

Doug White

Senior Editor

Doug White, a long-time leader in the nation's philanthropic community, is an author, professor, and an advisor to nonprofit organizations and philanthropists. He is the director of Columbia University's Master of Science in Fundraising Management program. He also teaches board governance, ethics and fundraising. His most recent book, “Abusing Donor Intent,” chronicles the historic lawsuit brought against Princeton University by the children of Charles and Marie Robertson, the couple who donated $35 million in 1961 to endow the graduate program at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Kent Allen

Journalist

Kent Allen is a longtime daily journalist and freelance writer. Over the past 20 years, while also writing about philanthropy and nonprofits, he has worked as an editor at The Washington Post, U.S. News & World Report and Congressional Quarterly. At present, Kent is a journalism and history teacher at The Field School, a middle and high school in Washington, D.C.

Lucy Bernholz

Journalist

Lucy Bernholz is a blogger and self-proclaimed “philanthropy wonk”. Her blog, Philanthropy 2173: The future of good, has been named a “best blog” by Fast Company and a “philanthropy game changer” by the Huffington Post.

Kim Breslin

Actor

Kim Breslin is an actress, comedienne, director, producer, artist, and chef. She has been an educator in North Philadelphia for 17 Years. Mother of two incredible children, she lives with her highly supportive cat, The Amazing Sid.

Cheryl Chapman

Journalist

Cheryl Chapman actively promotes philanthropy in the UK and globally via her journalism. She was the editor of Philanthopy UK: Inspiring Giving and now heads City Philanthropy, London, as its Director.

Stephen Dunn

Poet

Stephen Dunn, Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, is the author of 11 collections of poems, including “Different Hours,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 2001.

Regan Good

Poet

Regan Good is a freelance writer and poet living in Brooklyn, New York. She has written for The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times Magazine and others. She is currently at work on a memoir about growing up in a family of writers.

Sharilyn Hale

Journalist

Sharilyn Hale, M.A., CFRE is Founder and Principal of Watermark Philanthropic Advising where she offers strategies for meaningful giving, receiving and leading. A practitioner, author and educator, she brings a global perspective on philanthropy having served the nonprofit sector across North America, Bermuda and the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. She holds a graduate degree in Philanthropy & Development and is past Chair of CFRE International, the global certification for professional fundraisers setting standards for ethical and accountable practices.

Crystal Hayling

Journalist

Believer in a better world. Uppity advocate for social change. Former philanthrapoid. Crystal lives in Singapore where she helps donors develop strategy for effective grantmaking. She serves on numerous boards, and is a speaker and writer on civil society. Twitter: chayling

Holly Howe

Journalist

Holly Howe is a strategic communications consultant with a particular focus on the arts. She works as a freelance journalist, writing for various publications including FAD, RWD, House (published by the Soho House group) and the Irish Examiner. She also runs the Culture Vultures, a networking group for people in media and the arts. She can be found tweeting at @ hollytorious and in her occasional spare moments, she posts on her blog www.postcardsfromholly.blogspot.com

Wangsheng Li

Journalist

Wangsheng Li is president of ZeShan Foundation (Hong Kong) and a Senior Fellow of the Synergos Institute (New York City).

Lisa Macdonald

Journalist

Lisa MacDonald is a freelance writer and editor based in Toronto. A passion for philanthropy drives her involvement in initiatives that bring information and innovative ideas to Canada’s nonprofit sector leaders. Tweet her at @lisalmacdonald.

Andrew MacLarty

Actor

Andrew MacLarty is a New York based actor who has appeared on Boardwalk Empire and White Collar. Non-profit work includes narration for Partnership for a Drug-Free America, performances at the United Nations for Hurricane Katrina relief benefit shows, and Barefoot Theater Company’s ROCKAWAY benefit for Hurricane Sandy victims.

Bruce Makous

Journalist

Bruce Makous, ChFC, CAP, CFRE, has been a professional fundraiser for over twenty-seven years, with leadership positions in major educational, healthcare, and arts organizations. In 2009, he was named by the Nonprofit Times one of the “Most Influential and Effective” fundraisers in the US.

Peter D. Michael

Actor

For over 20 years, Peter D. Michael has been an established actor, voiceover talent and stand-up comedian. He is also an Emmy award winner.

Suzanne Reisman

Journalist

Suzanne is a U.S. international private client lawyer based in London. Suzanne assists philanthropists, their foundations, and international charities with cross-border philanthropy.

Julie Shafer

Journalist

Founder of Julie Shafer Development + Philanthropy, a national philanthropy consulting firm. Ms. Shafer offers a multifaceted skill set honed throughout 20 years as a philanthropy executive bringing a translational approach that bridges the gaps between philanthropists and non-profits.

Jade Shames

Playwright

Jade Shames is an award-winning writer living in Brooklyn, NY. His work can be found in The Best American Poetry blog, The LA Weekly, HOW art and literary journal, and more. He was awarded a creative writing scholarship to attend The New School where he received his MFA.

Amy Singer

Journalist

Amy Singer teaches Ottoman and Turkish history, as well as courses on Islamic philanthropy and the history of charity in the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University. Her recent publications include the book "Charity in Islamic Societies", and in 2008 she was awarded the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Award.

Sharit Tarabay

Artist

Sharit Tarabay painted the portrait of Gerry Lenfest. He is a painter and illustrator living in Montreal. He has his works published in magazines and books around the world.

James V. Toscano

Journalist

Jim Toscano is a principal in the consulting firm, Toscano Advisors, LLC, and an adjunct professor at the School of Business, Hamline University. Recently retired as president of the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, the cardiovascular research and education center of Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, he is a past chair of the Minnesota Charities Review Council and board member of Minnesota Council of Nonprofits.

Susan Yu

Journalist

Susan Yu is a journalist from the San Francisco Bay Area. She is an award-winning news reporter who was formerly based in Hong Kong for 14 years covering stories in Asia for international news media organisations. She is currently based in the United Kingdom where she freelances as a writer, editor and documentary film producer.

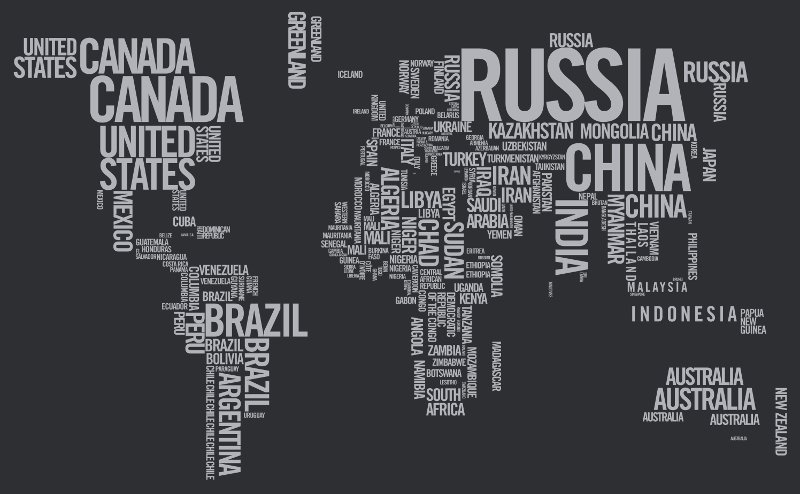

The Philanthropist Voice Worldwide

By The Editors

Why quiet, modest or so-called “humble” philanthropy is muting the potential for giving in countries across the globe.

Billions of dollars are being devoted to vital causes across the world in almost complete silence. Those making a difference with donations are usually successful and creative people of intelligence and compassion whose opinions deserve to be heard.

But quiet philanthropists rarely discuss the who, what or—most importantly—why of their giving. If asked privately, they talk of not wanting any attention, preferring a low profile or even being embarrassed by their wealth. Some suggest that talking about oneself and personal giving is not part of their culture.

But such unassuming generosity is being challenged by the causes they support as well as by their fellow philanthropists. Those who want to add decibels to donations have good reasons for urging philanthropists to speak out.

A big gift that’s well publicized can have double the impact of one that’s made covertly. The recipient gets a boost of confidence. Thought leaders and decision makers, from governments to nonprofits, sit up and pay more attention—and, perhaps, match funds—to previously overlooked issues.

And finally, where one leads, others follow. When a philanthropist endorses a cause with support on a large scale, others follow suit, and give big.

By going public, philanthropists bring others into the sunlight, helping generate a tradition and expectation of generous philanthropy amongst their peers. Those keen to see more and better giving largely reject donor concerns about negative perceptions or unwanted attention. Instead, they note that publicized gifts can encourage awareness, understanding and empathy—and, ultimately, commitment by others.

They point to philanthropists like Hong Kong’s James Chen, who contests the claim that Asian cultures are among those requiring the silent approach. Rather, he notes that the Chinese are among the world’s biggest enthusiasts for sharing their lives through social media.

Perhaps the best evidence comes from the experience of the United States, where between those who give prominently—from Rockefeller and Ford to Gates and Buffet—and the millions that make up “the crowd,” the philanthropic voice is strong.

In recent years, countries that have cultivated and supported the voice of their philanthropists have reaped the reward of a strong and expanding philanthropic culture. It’s no surprise so many are waiting for more donors to speak up.

Fun•lan•thro•py

By Roberta d’Eustachio

Philanthropists everywhere are talking about "Fun" in philanthropy. What does "Fun" mean?

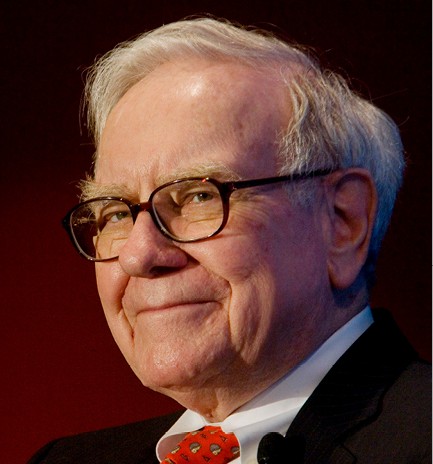

When Warren Buffet gave over $30 billion to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, one word turned up consistently in the media coverage: "fun."

Warren Buffet

Warren BuffetThe foundation’s official announcement of the gift read, “Warren’s wisdom will help us do a better job and make it more fun at the same time.” Buffet himself explained his decision by saying, “Over the years I had gotten to know Bill and Melinda Gates well, spent a lot of time with them having fun and, way beyond that, had grown to admire what they were doing with their foundation.” On the Charlie Rose show, Bill Gates said of Buffet, “The thing that stunned me the most after I met Warren … was that he was really having fun. I knew how to have fun, but not at that level.”

Observers like PC Magazine’s John Dvorak picked up the thread: “[Gates] will now have the stature of a King rather than that of a savvy entrepreneur. Big difference, and more fun.”

Here at Giving Magazine, that got us thinking. Is fun an essential element of philanthropy? Should philanthropists expect to have fun? What kind of fun? Is it possible to have too much fun? Clearly it’s important for anyone to enjoy their work, if they want to do it for long. On the other hand, the word “fun” conveys a sense of frivolity that seems wholly out of place when talking about responsible giving.

Which is why Alexis de Raadt-St. James, a philanthropist based in San Francisco, cringed when she heard Gates use the word. “The first thing that came into my mind was, this is too flippant,” she said. “Somebody didn’t coach him very well.”

Alexis de Raadt St. James

Alexis de Raadt St. JamesDe Raadt-St. James, who is the CEO of her family’s Althea Foundation, is deeply engaged with a portfolio of causes that are about as un-fun as can be imagined: mental health, depression, suicide and death. She was spurred into philanthropy by a series of traumatic events, including the deaths of loved ones and the 9/11 attacks, which left her shaken and anxious to help others. She has no interest in gala balls. “I don’t like the word fun at all,” she said. “I think it’s so trivializing.”

So when she heard the coverage of the Buffet gift, she sat down and wrote Gates a letter, explaining that, as a fellow philanthropist, she didn’t think that “fun” was the best word to use, if only because it would give people the wrong idea about philanthropy. “I would never use that word to describe what I do,” she said. “I work very hard at what I do.”

But even a short conversation reveals that de Raadt- St. James does draw great pleasure from her work, even when it has nothing to do with fun at all. Furthermore, it is clear that the pleasure helps drive the work and ultimately makes her effective.

Among de Raadt-St. James’s proudest achievements, for example, is a death-notice protocol – basically, a conversation guide that can be used to help health care professionals, military personnel, or friends and family notify others of the death of a loved one in the best possible way, minimizing the trauma experienced by both the bearers and the recipients of the shocking news. Her own personal experiences and subsequent conversations with soldiers and others convinced her that people need help navigating these singularly painful moments.

“I’ve had grown [military] men in my office in tears, telling me, ‘It killed me to say this. It killed me to talk to these parents,’” de Raadt-St. James said. So she spent years and over a million dollars to develop a death notification guide based on the highest psychological and medical standards. Today, her protocol is available to the public for free, and it is used by the U.S. military and the U.K.’s Scotland Yard.

And as serious as such a project is, de Raadt-St. James readily admits that she enjoys both the process and the results. Developing the protocol allowed her to combine her skills in education, science and communications. Now that it is in use, she gets a steady stream of letters and emails from users who tell her how much her work has helped them. “These are things that are helping change people’s lives,” de Raadt-St. James said. “It’s not glamorous, it’s not sexy, but it is fulfilling. Incredibly fulfilling.”

While that may not be “fun,” exactly, it is close. “Fun, I think, is another word for fulfillment,” she said. “And I receive great rewards from what I do. Handing someone a dollar won’t change their lives. But giving someone a modicum of hope, that can be transformative.”

Ultimately, de Raadt-St. James’s problem with Gates’ statement was more semantic than anything else. Her concern was that the foundation sent the wrong message about its seriousness. But if managing huge ambitious projects worth billions of dollars is “fun” for Bill and Melinda Gates, she said, then that can only be a good thing; it will increase the chances that they’ll stay engaged and be effective.

Kevin Murphy believes in fun, and he’s not afraid to say it. Murphy runs the Berks County Community Foundation, just outside of Philadelphia and is also the Chair of the Council on Foundations, a membership group based in Washington, D.C., including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Kevin Murphy

Kevin MurphyMurphy’s is the kind of foundation that gets involved in every kind of project imaginable, from scholarships to environmental protection to historic renovations. Doing so requires him to deal with donors large and small, from first-timers to long-timers. When he spoke to Giving, he was in the midst of preparing a dinner for prospective donors. His menu included tilapia in a mango-tequila sauce. Fun was definitely on the evening’s agenda.

But for Murphy, “fun” means a lot more than a nice dinner party. Fun means engaged, effective donors. “Fun and effectiveness – it’s not a very big leap,” he said. “None of us do very well at a job that we don’t enjoy. Whether you’re a CEO or a basketball player – it doesn’t matter – you’ve got to enjoy what you do to be effective at it.”

So when Murphy is getting to know a particular donor, one of his first challenges is to find out what is going to engage that person. That, in turn, requires some careful probing. “I ask, when you wake up at night, what are you worrying about?” he said. “Because [having] fun is about making an impact, so you don’t have to worry about it anymore.”

Melissa Berman

Melissa BermanMelissa Berman, CEO of Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, echoed Murphy’s words. “The issue of fun is a very powerful one for many of the donors we work with,” she said. Donors who enjoy themselves and their work are more engaged, make more gifts, and ultimately stay longer in the field, she said. “We think it’s in the interest of the nonprofit sector for philanthropy to be engaging and addictive.”

Like Murphy, Berman’s first step with a prospective donor is to help them chart a course that they will enjoy following. She sits down with clients and looks for the answers to four sets of questions: • First, what are your motives? What brings you to the field? Why are you giving? What do you hope to get out of it? • Second, what issues engage you? Is there a particular area of concern? • Third, do you have a preferred approach to solving the problem? • Do you want to work locally, or globally, or at a policy level, or a direct service level? Do you want to use a tried-and-true method, or experiment with new approaches? • And finally, Berman asks, how, specifically, do you want to be involved? Do you want to be heavily engaged? Do you want to stay in the background? Do you want to travel the world? Do you have obligations that keep you close to home? Armed with answers to questions like these, Berman said, she can help clients avoid getting involved in things that they don’t enjoy. “Philanthropy is a voluntary decision,” she said. “If it’s something you have to do, it’s work. If it’s something you have to pay, it’s a tax. Philanthropy shouldn’t be work, and it shouldn’t be a tax.”

Andras Szanto

Andras SzantoAnd just as those who advise donors must consider the pleasure principles, so too must those who solicit donations. “People are motivated by pleasure,” said Andras Szanto, an advisor of the Wealth & Giving Forum, a New York-based organization that helps high-value individuals and families network among themselves. “Why shouldn’t philanthropy be like anything else? We are in a very unusual stage in history where we have a large number of people who can ask, ‘If I’m not having fun, then why am I here?’”

Institutions and organizations have no choice but to consider their prospective donors’ definition of “fun,” he explained. “The other day I was at the opening of the fall season at one of the major music organizations here [in New York]. The gala, you know,” he said. “And I looked over the audience, and half of them are in their tuxes and gowns. But the other half is in their regular concert-going attire. And I’m thinking to myself that this institution may be in trouble a few years down the road. One generation’s fun is not another’s.

“As we go through a cultural change in philanthropy, as a new generation comes in, the definition of fun changes. They might be trying to attract people to a gala who would rather be in a tent in the rain forest.”

So the word ‘fun,’ despite its lightweight implications, actually represents a profoundly important concept for everyone in the philanthropic field. Advisors need to consider it to help donors make good decisions. Would-be grantees need to consider it in order to attract donations and keep donors engaged. Donors need to consider it if they are to understand which of countless options for investment and involvement suits them best.But is there a danger in too much fun? There is, givers and advisors say, and it arrives when the donor’s pleasure takes precedence over the work needed to serve the philanthropic mission. “I suppose that the dark end of this is a form of narcissism – you’re just in it for yourself,” said Szanto. “As with anything, there are extremes. You don’t want philanthropy to turn into an action sport.”

Keith Whitaker

Keith WhitakerThe solution, donors, advisors, and grantseekers say, is to make sure that the giver understands the recipients' intention and that the goal is not to have fun, but to make the work fun. Keith Whitaker, a philanthropist in his own right and also a fellow at Boston College’s Center on Wealth and Philanthropy, has seen people get in trouble by aiming for fun as an end in itself. “Almost every client we see comes in with this as an underlying psychic state: ‘I want to have fun with my kids in our foundation,’” he said.

The problems come, Whitaker said, as the work – along with conflicting opinions about the work – piles up. His solution is to steer such donors away from questions about what they want personally, and towards questions about what their grantees need.

Focusing on the outcomes has the ironic result of making the work more fun. “One of the best things that an advisor can do is say, ‘Your fundamental instincts are correct. It’s your money, and just think of the great things you can do with it that will add to your happiness and your family’s happiness.’” Whitaker said. “What’s made it more fun [for many families] is really being clear about the family’s roles, and understanding the recipients’ needs – looking to others.

“I’m not trying to distinguish happiness from work. Happiness is work. Do I want my life to be about sitting back and drinking margaritas? When I talk to folks, I always say, ‘This is going to be lots of fun for you. And it’s also going to be a lot of work.”

If anyone understands that work is the critical element of successful giving, it’s Mario Morino, the Cleveland- based philanthropist who chairs the Venture Philanthropy Partners and the Morino Institute. What makes a successful philanthropist, Morino said, is not the ability to have fun, but the drive to do the work in the first place. In his experience, that drive is rarely fueled by a desire for pleasure.

Mario Morino

Mario MorinoInstead, it is powered by deeper forces. “I don’t think ‘fun’ drives somebody,” Morino said. “I think their enduring values are what drives them. The thing that makes the human soul persevere is purpose.” Morino’s personal purpose is to help impoverished children. This springs from a core belief that everyone is entitled to the same shot at education and success that he had. “I was not rich in money, but I was rich in family, and teachers and so on,” said Morino. “I had a great life. I go back to that same neighborhood and now it’s really rough. Those kids don’t have one thousandth of the chance I had to live the American dream.”

The fun he gets from the work comes through the particular methods he uses to pursue his purpose – setting up new projects and watching to see if they thrive. “I love building something,” he said. “The joy comes from building and solving.”

Thus Morino finds a fun means to address a deeply motivating purpose. His challenge to any would-be philanthropists that he meets is to identify their own purpose first, before they think about fun things to do. The purpose is the driving force; the fun is the grease that keeps the wheels turning. Without the driving force, he says, no amount of fun will keep a donor engaged beyond a check-writing level.

Philanthropists’ purpose may come from their religious beliefs, their family’s values, or even from tragic events that changed their life’s course (like de Raadt-St. James’ string of personal losses). But the purpose has to be there.

“If I don’t see one [a purpose] in place, then I know they’re not going to stick,” Morino said. “What is it you really want to do? Know that. Maybe you don’t tell anybody, but know it. Otherwise, you start smoking your own fumes. The whole thing is designed to make a donor feel like God. Fall into that and you start making bad decisions.”

When Morino heard the Bill Gates interview, he immediately recognized the spirit of the fun-loving, problem-solving entrepreneur in action. “I don’t know Bill, but I know a lot of people like Bill,” Morino said. “What they’d say is, ‘This is a bear of a problem, and really tough to solve, and it’s going to be fun to try to solve it.”

But he also recognized a man with a mission that goes beyond pleasing himself. And indeed, if one goes beyond the initial coverage of the Buffet-Gates gift, it becomes clear that both Buffet and Gates are motivated not by a desire to have fun, but a desire to solve a specific kind of global injustice.

In the Charlie Rose interviews, it is obvious that the two men richly enjoy each other’s company, and that they have a lot of fun together. But both Gates and Buffet stressed that they share a desire to grapple with the kinds of health and education challenges that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has embraced. “Bill is an American, but he’s basically a citizen of the world,” Buffet told Rose. “He has a world view. He thinks that the child in India is as valuable as the child next door, and he lives it. It comes out in how his foundation operates.”

It is the last point that sealed the deal for Buffet when it came time to put his billions to work for the public good. Like so many philanthropists, Buffet and Gates are clearly not afraid of fun. They recognize its utility. But just as clearly, they recognize that if the responsible philanthropist is to have fun, it should be fun with a purpose.

Ambassadors for Philanthropy?

By Dame Stephanie Shirley

The British Government’s Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy revisits her appointment.

The call from the Cabinet Office came in March 2009. Would I be interested in being appointed as Britain’s first- ever Ambassador for Philanthropy? Many said, after the fact, that I was a logical choice: I was self-made and had given generously to autism research and technology and was at home talking about all aspects of giving. I weighed the offer for about five minutes, and promptly signed on.

In the end, the position turned out to be both more and less than I initially imagined. We had few victories in a push to truly unleash giving in Britain. A year is a very short time. But, while the ambassadorship expired with the Labour government in 2010, it led to a number of developments that continue to this day.

It wasn’t long after taking the honorary position that the penny dropped—literally. I’d assumed that the undertaking would be allocated some funds for expenses, travel, and related activities such as research and aggressive outreach. However, I learned, the maximum government contribution would be roughly £10k and that amount was meant to cover the overhead for meetings in Admiralty Arch, at the time a government owned, iconic building in central London, and cups of tea for my guests.

Ultimately, I met the direct costs—approximately £250,0000—myself. And while Prime Minister Gordon Brown did finance a promotional video endorsing my ambassadorship, I was mostly on my own, and that fit the entrepreneur in me just fine. Because the ambassadorship itself was ill-defined, its existence was never properly discussed, evaluated, or, for that matter, acknowledged. I’d hoped that Whitehall would supply data to support the work, but they didn’t seem to know how much the government itself was allocating to “good works.” And agencies that did give significantly to developing countries, such as the Department for International Development, were looked at disapprovingly as overstepping colonialists.

Then an election was announced, and everything stopped. The office of the Ambassador for Philanthropy was closed officially nearly as abruptly as it was announced. But the closure didn’t stop us from carrying on privately and forming a purpose driven enterprise under the name— Ambassadors for Philanthropy—with a manifesto of unleashing giving worldwide.

When we set out, I’d known that the non-profit sector had a voice, and financial institutions and their philanthropic advisors, including attorneys, had a booming one, but philanthropists themselves were often unheard and underreported. With the Ambassadorship and after, I decided to focus our attention on philanthropists and giving them a voice.

Historically, the British rarely talk about money or what we do with it. To a degree, we began to change that paradigm. We promoted philanthropy as an activity to be enjoyed and celebrated and urged media outlets to report on philanthropists as individuals whose generosity should be examined as to its success, intention and impact, rather than solely as people whose wealth should be coveted. I delivered some 40 speeches throughout the country to promote this view. We persuaded philanthropists who’d never before discussed their giving publicly to speak up on camera. And when other countries expressed interest, our movement began to grow, initially within the Commonwealth, and then eventually worldwide.

Although the initial position was a creation of the British government, we were able to evolve and activate many of the ideas that emerged from the experience, including the curation of the digital publication you are now reading.

And while we didn’t provide the type of transformational change we’d hoped for in Britain, we at least helped preserve the benefits of philanthropy within the country. In mid-2012, the Conservative government proposed a tax action that would have sharply curtailed incentives for donors to give and give generously. Thankfully, we were able, along with others, including our network of philanthropists, to rally strong opposition to this measure, and the plan was eventually scrapped.

The philanthropist voice lives on!

Terrorist Funding and Philanthropy

By Suzanne Reisman

One person's terrorist may be another's freedom fighter.

Atrocities, biological warfare, carnage. Aid, best practices, country building. Such are the ABCs of philanthropy in war-torn countries like Syria and the Sudan. While one person’s terrorist may be another’s freedom fighter, the same tragedies are suffered by all sides. And philanthropists who try to alleviate that suffering must negotiate their own minefields, strewn with a morass of government regulation and the threat of fines and criminal prosecution.

Syria is a prime example. It is common knowledge that while the world watches the unimaginable atrocities visited upon its civilian population, donations are frequently intercepted by members of ISIS (otherwise known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria). In some instances brave individuals are driving cash and supplies over the borders, attempting to ensure that philanthropic aid is not diverted before it reaches its intended beneficiaries. The Charity Commission of England and Wales has recently published guidance that acknowledges the importance of providing humanitarian aid to those in Syria while warning of various obstacles, which in addition to the obvious physical dangers, include inadvertently engaging in terrorist financing. Syria is subject to a broad sanctions program administered by the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Financial Assets Control (OFAC) in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security, which apply to all U.S. citizens as well as U.S. entities such as private foundations and other 501(c)(3) organizations. U.S. charities that wish to make donations to Syrian charities must apply for a license from OFAC. Otherwise donations may be made to a U.S. charity that is registered under the OFAC Syria sanctions program or to a charity in a third country.

The most prudent and, in many cases, the most effective strategy is to work through NGOs with significant experience in the region. A Gulf-based donor with close ties to Syria has suggested that Médicins Sans Frontières, as well as the Maram Foundation and Karam, both of which are U.S. charities, continue to be successful in delivering aid to those affected by the Syrian crisis. The Maram Foundation runs the Atmeh Refugee Camp in Idleb, Syria’s largest refugee camp for internally displaced people, providing all food, medical and hygiene supplies. Karam operates a range of projects on the ground within Syria, including vital food distribution, and social and educational projects.

Of course Syria is not the only country in need of humanitarian assistance. It is however, along with Burma (Myanmar), Cuba, Iran and the Sudan, the subject of comprehensive OFAC sanctions programs. Sanctions and other anti-terrorist legislation have long been a part of governments’ foreign policy arsenal.

Various governments and international organizations (including the Financial Action Task Force, the European Union, and the United Nations) have issued guidance and sanctions in an effort to combat terrorism. Various countries, including the United States and the European Union, have also enacted anti-bribery legislation that impacts charities. The regulations and guidance issued by OFAC and the U.S. Department of Commerce include detailed guidance for U.S. donors and their foundations. They are also relevant for non-U.S. donors who may wish to fund projects by making grants to or partnering with U.S.-based NGOs. OFAC has also issued “Anti-Terrorist Financing Guidelines: Voluntary Best Practices for U.S.- Based Charities” which are, as the name suggests, voluntary but may be useful to many donors. (These guidelines in particular have also been the subject of significant criticism.)

As a general matter, donors may begin their due diligence by reviewing the “Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List,” or SDN list, published by the United States and the United Kingdom’s consolidated list, which includes those persons and entities on the European Union’s and United Nations’ lists. The U.S. list includes individuals and entities throughout the world (including the United States) that are designated due to their activities in targeted countries as well as others such as terrorists and narcotics traffickers. Regardless of whether an entity or individual is on an SDN list, donors are required to undertake their own due diligence to determine if they are providing assets or services to entities that are owned, controlled by or acting on behalf of a person or entity on the SDN list.

The SDN lists can be problematic. Once an individual or organization appears on the list, it can be difficult to get off, regardless of circumstances. On July 18, 2013, the European Court of Justice issued an opinion confirming that the procedures used to list the plaintiff, whose removal from the list had been recommended over 10 years ago by the United Nations, were flawed. One U.S. court has found that the U.S. government froze charitable assets without probable cause, in violation of the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. A second district court determined that illegal wiretaps were used to gather evidence supporting inclusion on the SDN list; however on appeal it was determined that the government had not waived sovereign immunity and the district court decision was vacated. OFAC issued guidance in 2010 relating the release of limited amounts of blocked funds to cover legal fees and costs incurred by U.S. persons who seek to challenge their designation as blocked persons.

The next step for charities interested in countries subject to sanctions programs is to review the relevant sanctions. Broadly speaking, the comprehensive sanctions programs allow for philanthropic activity through either general licenses (which may require reporting but do not require a license before the activity takes place) or specific licenses, which apply specifically to the applicant. Sanctions programs are subject to change at any time—changing even as this article was written. Donors are encouraged to continuously monitor OFAC licensing procedures and related guidance and regulations.

The United States first imposed sanctions on Burma in 1988 when it suspended aid to the country after the shooting of protesters by the military junta. Humanitarian assistance was permitted to continue. In light of the momentous changes that have taken place in the country over the past few years, the United States has eased its policy, paving the way for full economic engagement with Burma, while at the same time providing safeguards in the event that the Burmese government changes its policies. Sanctions relating to philanthropy have been eased accordingly. In April 2012, OFAC expanded the types of support for humanitarian, religious and other non- profit activities that could be provided in Burma, provided that they do not benefit any “blocked persons.” These developments should also pave the way for the creation of micro-finance projects in Burma.

Up until the recent announcement of reinstated relations between the two countries, OFAC maintained a comprehensive sanctions program against Cuba, and a new FAQ published by the Treasury Department updates the information as of January; licenses are available for a wide variety of philanthropic undertakings. The thawing of U.S. relations with Iran, historically referenced as part of the “axis of evil,” is also evident in the easing of OFAC’s sanctions programs. On September 10, 2013, OFAC issued two new general licenses as part of the Iran Transactions and Sanctions Regulations. One authorizes NGOs to export services to Iran in support of non-profit activities, subject to certain reporting requirements and a cap of $500,000 on the transfer of funds over a 12-month period. The other authorizes the importation and exportation of certain professional and amateur sports services and exchanges, including activities related to exhibition matches, sponsorship or players coaching, refereeing and training.

OFAC sanctions apply differently to different regions of the Sudan and to a large extent no longer apply to the Republic of South Sudan, which gained its independence in 2011. Generally, humanitarian relief is permitted in Darfur and “specified regions” of Sudan and favorable licensing policies are applicable in other regions. It appears that relations with the Sudan may be easing as well in light of a deal struck between the U.S. company, General Electric, in the Sudan and a reported statement by Sudanese Foreign Minister Ali Kharti that several U.S. companies which applied for licenses to operate in Sudan were granted, which he believes “is an indicator that investments and commercial relations could overcome political difficulties.” In the meantime, it is permissible to donate articles that relieve human suffering such as food, clothing and medicine.

The United States has targeted programs which prevent individuals from doing business with blocked persons in Somalia, Western Balkans, Belarus, Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Liberia (Former Regime of Charles Taylor), Persons Undermining the Sovereignty of Lebanon or Its Democratic Processes and Institutions, Libya, North Korea, Somalia and Zimbabwe, as well as other programs targeting individuals and entities around the world. In certain cases OFAC has been more flexible. For example, the U.S. Treasury website’s Frequently Asked Questions regarding private relief efforts in Somalia recognize that, due to the highly unstable environment and urgent humanitarian needs in the country, some food, medicine or payments may unintentionally be provided to al-Shabaab, a terrorist group. The FAQs state that, so long as the donor did not have reason to know it was dealing with al-Shabaab, “such incidental benefits . . . would not be a focus for OFAC sanctions enforcement.”

Legitimate concerns have been raised about the breadth of the power that governments may marshal to investigate and audit philanthropic endeavors and freeze assets. Depending on where one’s sympathies lie, these sanctions may be seen as necessary or the misguided edicts of Western governments. Some jurisdictions such as the European Union have promulgated regulations prohibiting compliance with U.S. sanctions where they conflict with the EU’s. Furthermore, the applications of sanctions may differ, based on whether the individual or entity is a charity, a corporation, or a branch of the U.S. government.

Chiquita Brands International Logo

Chiquita Brands International LogoTake, for example, the case of Chiquita Brands International (“Chiquita”), which through its Banadex Unit owned banana operations in Colombia. From 1997 to 2004 Banadex made payments to United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (also known as AUC), a violent paramilitary and drug trafficking organization, for protection from guerrillas that had previously murdered Chiquita employees. As of September 10, 2001, it was a crime to finance AUC. In 2004 Chiquita sold Banadex to Banacol, which then provided bananas to Chiquita. Chiquita was subsequently indicted by the U.S. Department of Justice in connection with its payments to AUC, and in 2007, pled guilty to doing business with a terrorist organization and paid a $25 million fine. However “Chiquita turned a $49.4 million profit from its Colombia operations during the period while it was making the illegal payments to the AUC. . . . Defendant Chiquita’s payments may have protected its workers while they were working on the company’s profitable farms, but Defendant Chiquita’s payments field the AUC’s terrorist violence everywhere else.” During the sentencing hearing Chiquita’s lawyer noted that Chiquita had voluntarily approached the Department of Justice when it asked whether it should stop making payments, the government’s response was equivocal. The “government did not want to say ‘stop’ explicitly because it did not want to have blood on its hands if someone was, in fact, killed. It couldn’t say ‘continue’ because it did not want to hurt its case and so it looked for...a middle ground.”

If a charity made payments to a “specially designated global terrorist” its assets would be frozen and likely its directors would be subject to prosecution. Apparently when a corporation makes such payments, it is one of the costs of doing business in Colombia.

Could Chiquita’s predicament have been resolved if NGOs had trained managers to use nonviolent methods of conflict resolution? In Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that it was a crime for a U.S. NGO to train Kurdish and Tamil groups on the SDN list to use peaceful methods of reaching their objectives, such as petitioning the United Nations and other entities and to engage in political advocacy for groups. Ironically while everyone’s stated wish is “world peace,” it is a crime to assist terrorists to find peaceable methods of making themselves heard on the world stage. While it is understandable that tax relief is denied those who assist parties who are not in alignment with U.S. foreign policy, providing groups designated as terrorists with alternatives to terrorism is also a laudable result.

While donors are required to follow these rules under threat of civil penalties and criminal prosecution, the U.S. government struggles to end its own terrorist financing. In his July 2013 Quarterly Report to the U.S. Congress, John F. Sopko, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) expressed concern about 43 cases in which material “supporters of the insurgency” in Afghanistan, including supporters of the Taliban, the Haqqani Network and al-Qaeda, had received government contracts. SIGAR reported that the Army Suspension and Debarment Office declined to act on these cases as it would violate the contractors’ due process rights if they were suspended or disbarred based upon classified information or findings of the Department of Commerce. Sopko concluded: “I am deeply troubled that the U.S. military can pursue, attack and even kill terrorists and their supporters, but that some in the U.S. government believe we cannot prevent these same people from receiving a government contract. I feel such a position is not only legally wrong, it is contrary to good public policy.... I continue to urge you to change this faulty policy and enforce the rule of common sense in the Amy’s suspension and debarment program.”

The New, New Philanthropists

By James V. Toscano

There is an emerging style of philanthropy that will not accept anything but solutions and cures.

There is an emerging style of philanthropy that will not accept anything but solutions and cures. Gradually it will constitute a significant element in the way society allocates charitable resources.

This new philanthropy is characterized by impatience, empiricism, and calculated risk—contradictory yet persistent aspects displayed by a new breed of donors. The division between for- and non-profit, the idea of tax deductibility, and public recognition of donations all seem to be losing importance.

This movement sees its contributions as investments, not charity. Societal return is the object. Is it philanthropy, or is it something else? Does it matter what we call it if it becomes a vital, dynamic force in societal change? In the truest meaning of the word, these individuals are philanthropists.

What is all-important is pushing the envelope, not accepting the status quo, and positive impact on the overall society.

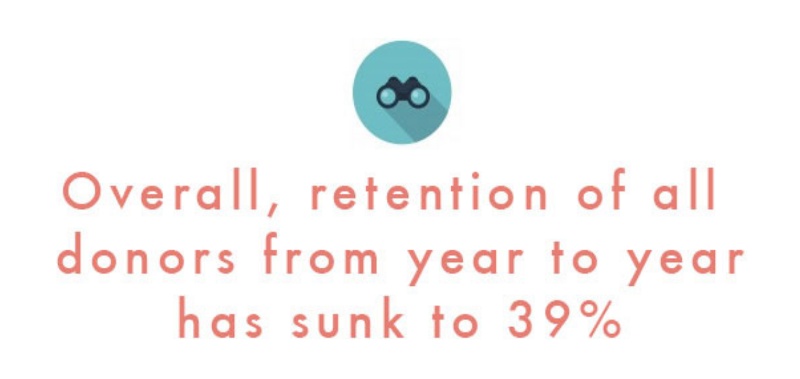

Traditional Philanthropy Is Slowing

With traditional philanthropy plateaued, perhaps even receding, it is this source of energy to which many will direct their focus for the resources needed to fuel the nonprofit sector and beyond.

The most recent survey of nonprofit organizations reports traditional methods of fundraising failing: three-quarters of new gifts are not repeated. Overall, retention of all donors from year to year has sunk to 39 percent.

The new philanthropists are really not interested in the same-old, same-old. For four decades, traditional philanthropy has constituted two percent of the GDP. These new minds know that four to five percent is needed, and they have a method for determining where to increase investments in society.

Generational differences, conceptual and methodological developments, different expectations, even the sources of wealth are motivating this change in the way we contribute time, money, and other resources.

The March to Measurement

Central to decision-making is measurement. For example, the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation’s David Hunter influenced foundations to seriously employ metrics in evaluations of proposals and nonprofits in managing to measurable outcomes.

Heavily influenced by the empiricism of hedge funds, leadership of the Robin Hood Foundation has pushed sophisticated metrics. To determine return on their charitable investments, now over $1 billion, the Foundation methodology monetizes all potential outcomes of their grants. This allows comparative evaluation and a system of counterfactuals, what would happen if no investment were made, gives credibility to the discipline used.

Robin Hood requires its recipients to be nonprofit organizations. Others are moving in a direction where the distinction between the nonprofit and the for-profit organization doesn’t matter.

Obliterating Boundaries

This newest attempt crosses, really obliterates boundaries between for-profit and nonprofit organizations, utilizing the strengths of both.

Entrepreneurial in spirit, bottom line and success oriented in methodology, disciplined in its choices, yet value-oriented in its mission, the new philanthropy seeks to solve problems, not merely to reduce or ameliorate them.

The greatest of all these challenges nationally and internationally is the growing inequality of income and total resources available to individuals.

The new philanthropists are beginning to focus on this problem, with a solution that principally focuses on a model of wealth creation and the promotion of social mobility.

In the past, attempts to reduce inequality have been piecemeal, especially when human beings are parsed into a variety of nonprofit and government services, assistances, and subsidies. Progress has been made, yet the number of poor here and abroad continues to increase.

Attempts at government intervention through aggressive taxation have largely failed, as have the inflating power of printing more money.

These government measures may have helped stop temporary dysfunctions but have not brought longer-term relief or, more important, solved the root of the problems.

Beginnings

The idea of philanthropic assistance in creating wealth is not new. Just look at the worldwide phenomenon of microloans, which have indeed promoted independence, employment, and wealth.

The difference now is that wealth creation is becoming the significant driver among those new philanthropists who value increasing social mobility, using their resources to achieve this important aspect of the American Dream.

The new philanthropists envision funding going beyond grants and loans to a new focus on investments in nonprofits, for-profits and any combination for solutions, for cures. They use rigorous metrics, leverage of all types, and intensive due diligence to find their philanthropic investment targets.

The Creation Of Wealth

Their targets for investment have high promise to create wealth not only for individuals but for communities, the groups that produce high-paying, long-term jobs for many currently under- and unemployed.

The existence of a grocery store in a poor neighborhood is a well-known engine to produce other economic development. Yet most blighted areas lack such stores. And if such a store is introduced, failure is often the outcome, given all of the missing elements to make a grocery store succeed.

To address the grocery story dilemma, a group is seeking to create a start-up in a neighborhood that raises fish and uses the fish water to grow hydroponic vegetables and herbs, providing communities with both nutritious food and jobs. Salaries are multipliers for economic growth. High quality food produces stronger and healthier children and adults. The downward spiral is reversed!

This new philanthropy focuses on emerging societal trends: the digital, the green, and the quality movements all around us. Nevertheless, two conventional areas needing vast new resources—the rebuilding of infrastructure and the capacity problems of health care— will need the same innovative solutions as the new and emerging areas of economic growth.

Opportunity Abounds

Opportunity abounds and the potential for wealth creation is enormous. Just think of an idea in a college dorm, develop the concept, go through rigorous due diligence, receive funding, and a new Facebook may be born.

Or an idea growing out of a public housing project that develops into a profitable ethnic restaurant at the new football stadium employing inner city workers is financed. How many more innovations and start-ups are created through this new philanthropy depends on how the ideas embodied in this approach catch on with increasing numbers of nontraditional donor/investors.

We need much more philanthropic investment if any of our ambitions to reduce inequality or to solve a myriad of other problems are to happen. And the new philanthropy may provide these resources.

Where will this come from? First remember that we are talking about grants, loans, and investments. If we create wealth, those beneficiaries may repay earlier grant funds to the source, or repay a loan with reasonable interest, declare dividends on investments, or return high yields on original investment equity.

One way to do this is for new philanthropists to come together and contribute to an impact fund that combines their values and their rigorous methodology. Community foundations may be the perfect place to start these funds. Through impact grants and loans, the fund can leverage bank loans, buy down mortgage points, capitalize initial efforts, and generally supply the start-up funds for a new innovation, a solution to a long-standing problem, or a cure for societal dysfunctions.

Starting The Fund

The impact fund will start with individuals of high net worth and farsighted foundations capitalizing the initial effort. However, anyone can contribute, loan money, or invest in this effort. For example, individuals with donor-directed funds can make grants to the fund, allow program related loans, and invest a small percentage of their corpus (say, five percent) in the fund.

Mutual funds and other investment houses already offer socially responsible funds that cover part of this territory but do not go to new combinations of groups, to highly adventurous ideas, or to nonprofits with entrepreneurial subsidiaries.

Eventually, anyone with an investment can place a percentage of their corpus in impact philanthropy funds— funds that seek not only entrepreneurial reward but also overall societal benefit.

Just think of a percentage of the endowment funds in foundations that might find their way into reasonable and responsible investments in these impact funds, given the foundations’ missions. Why just use the earnings of the endowment? Use the endowments themselves.

Is there risk? Not risk, risks. Many. And rewards. More than can ever be achieved without this new approach—the very real creation of wealth across a spectrum of diverse ideas, industries, communities, and individuals.

We need new blood in the philanthropic system. We certainly need more funds. We need new ideas. We need societal venture funds. We need new ways of philanthropic investing. We need new metrics. We really need these new, new philanthropists.

Futures

By Lucy Bernholz

The do's and don'ts of citizen surveillance, Sudan and George Clooney.

Celebrities know a lot about being watched. Maybe that’s one reason for actor George Clooney’s enthusiasm for the satellite camera he’s trained on Sudan.

Sudan has been a longstanding interest for the actor. He’s testified before Congress about the country, and in June 2012 was arrested for protesting outside the Sudanese embassy in Washington, DC, against alleged war criminal President Omar al-Bashir. Since 2010 he’s also funded the Satellite Sentinel Project (SSP), an organization that independently observes the volatile border between Sudan and South Sudan. SSP has become not only a witness to genocide, it is opening up a new frontier in civilian humanitarian aid.

Working through partnerships with the Enough! Project, DigitalGlobe, Google and the Harvard Humanitarian Institute, SSP pairs satellite imagery with on-the-ground mapmakers and analysts. The project tracks military movements, records human rights violations, and builds an evidence base of satellite images paired with reports and data from the field. Even in an age of widespread government surveillance, SSP represents a number of ‘firsts.’ It is a groundbreaking application of military technology within civilian peacekeeping; it is a unique partnership between tech companies, scholars and aid workers; and it brings new data to bear on international policy.

For a full year beginning in 2011, the SSP recorded more than 25 violations of existing peace agreements and military movements that threatened Sudanese villages and people. The broad peripheral vision of the satellites also ensured that the movements on both sides—government as well as rebel forces—were captured. Satellite images of mass graves and smoldering villages provided incontrovertible evidence of events previously hinted at by those on the ground. They not only revealed the extent of the damage, but could be knit together to show the direction and pace of destruction in the wake of moving troops.

It wasn’t long before project leaders recognized that the combination of satellite imagery and ground level analysis could be used to predict future disasters. In September 2011, for example, SSP analysts realized that their satellite images of troop movements pointed to a surefire attack on the village of Kurmulk. They took the unusual step, as a watchdog organization, of issuing a warning, and thousands of people were able to flee ahead of the onslaught.

Not surprisingly, the international response to SSP’s images lags significantly behind the technology. For the humanitarian aid community, however, SSP has signaled a sea change. Humanitarian groups are mostly trained to respond to crises, not to avert them. Nonintervention has been a stalwart feature of humanitarian aid for centuries, and a key reason these groups are given access to war zones in the first place. Changing their rules of engagement may mean saving lives in the near term, but could also result in being banned from conflict zones the next time around. Actively shaping the direction of a conflict means new responsibilities and the need for an updated code of ethics.

The SSP is teaching us that new technology can be applied to humanitarian aid faster than we can predict the consequences of doing so. This is often true of cutting-edge technologies. But rarely is it a matter of life or death.

The Top People

By Nelson Aldrich, Jr

The fate of almost everything that's good, true and beautiful in America is in the hands of that exclusive group called trustees.

Do you remember Jean-Marie Messier? A little over a decade ago, in New York City’s philanthropic circles, the then chief executive of the Franco-American company Universal-Vivendi was the toast of the town. Literally (in that fund-raising season Messier was toasted at benefits for the New York Public Library, the Appeal of Conscience Foundation, and the Robin Hood Foundation) and figuratively speaking, too. At the time the Whitney Museum and the Museum of Radio and Television had made him a trustee; he was being considered for the board of the Metropolitan Opera; and his wife, Antoinette, was on the board of the New York Philharmonic. Less than a year later, with Universal-Vivendi’s stock in free fall and his own corporate vainglory under harsh scrutiny in Paris and New York, Jean-Marie Messier was toast. The moral of the Messier story was summed up by the woman who had wooed him for the board of the New York Public Library, Elizabeth Rohatyn, wife of the investment banker and former ambassador to France, Felix Rohatyn, and herself a notably public-spirited figure in the city. “When new top people come to New York, everybody wants them,” she said.

Let’s unpack that. “Top people” is an obviously enviable social niche. We all want to be ‘at the top’ in some category or other—a top dermatologist, say, or a top golfer at the club, or a top government official, or a top stamp collector. But to be among the top people is a different kind of wonder.

Jean-Marie Messier

Jean-Marie MessierAnd to discover who belongs in it and how they got there, you need only look at the second clause of Elizabeth Rohatyn’s sentence. Who is “everybody” and for what, exactly, are the top people wanted? Jean-Marie Messier’s story holds the answer. “Everybody” refers to the guardians of a city’s nonprofit, nongovernmental institutions— principally other top people—and what they want from new top people is money, and as much as possible. In the course of Messier’s brief sojourn among the top people of New York, for example, he committed himself and his corporation to giving many hundreds of thousands of dollars to the civic institutions that had honored him with their toasts and, much more importantly, with a seat on their board of trustees. For all intents and purposes, in American society today “top people” and “trustees” are hyphenated terms, and the hyphen is a placeholder for money.

This arrangement, in reality as on paper, is unique in the modern world, and a bit breathtaking on the rare occasion someone takes a closer look. Trustees, as a group of people, often have in their charge an astonishing portion of the entire high-culture heritage of the nation, a very large part of its educational, scientific and medical institutions, ideological seedbeds of social and foreign policy called think tanks, agencies of social service and economic betterment, and vast and growing chunks of the country’s land itself.

For well over 200 years the system has straddled the encroachments of government bureaucracy and politics on one side and the clutch of private enterprise on the other. Protecting the tradition was precisely the intent of the Supreme Court in the famed Dartmouth case of 1819 that decided to create and protect a civic space where private money could accomplish public purposes in the unending struggle against misery, ignorance, and ugliness. The system is also the envy of some European politicians who want “voluntary taxation” to relieve them of the onus of having to support their nation’s cultural heritage with direct taxation. Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi, for example, before his more recent controversy, wanted to take the alarming step—alarming to some lovers of art, anyway—of “privatizing” the glorious museums and churches of Italy.

Everywhere these days one hears loud cries for more “transparency” and “accountability” in corporate governance. But when it comes to the governance of nonprofits, there is only silence. A case in point: Business Week once ran an excited story about the bold drive of Harvard’s then president, Lawrence Summers, to reform just about everything in the university, and the grim opposition he was running up against from just about everyone. Everyone, that is, but the trustees (called The Corporation). This handful of men had chosen Summers as president, presumably after listening to what he wanted to do in that office, and after giving him firm assurances of their support. But Business Week did not so much as mention Harvard’s trustees.

This may be changing, however. Scandal has a way of attracting inquiry and inquiry can reveal structures that underlie the story of who did what to whom. The fact is that opportunities for abuse of trust by trustees are abundant in nonprofits, and some abuses are getting front-page coverage these days. The board of Boy Scouts of America is under surveillance by the media for its struggle with gay rights. Susan G. Komen, the cancer charity, recently underwent a leadership change in the wake of a scandal involving a board decision to deny funding to Planned Parenthood and continues to draw ire for its CEO’s grandiose salary. The Hershey School in Pennsylvania, with its $12 billion endowment, has been under siege by some of its most loyal alumni because of perceived conflicts of interest on the part of board members.

A few voices murmur of crisis in American trusteeship. There are too many nonprofits and too few available trustees. For one thing, a position that once brought little but honor now holds the possibility of dishonor as well, through liability to prosecution. For another and more important thing, trusteeship is at risk of becoming an onerous task and of going the way of other forms of civic participation. The problem seems to be one of time. Fifty years ago, most trustees were recruited from the ranks of the more or less leisured class, so-called old money.

Elizabeth Rohatyn

Elizabeth RohatynBut old money being almost by definition these days no money, its representatives have been replaced by new money (“new top people,” as Ms. Rohatyn put it)—that is, by folks who, again almost by definition, are extremely busy making money. And though this talent makes them attractive as donors, it might make them less so as competent, attentive trustees.

A talent for money-making is often paired with a penchant for ‘free market’ solutions to nonprofit problems. There was a time, for example, when the galleries of the new museum of German and Austrian art on New York’s museum mile were open three days a week, while the museum shop and the restaurant were open four. Or, to take a more poignant example, consider the case of the passionate and sole supporter of a modern dance group who asked one of his businessmen trustees to help him decide whether to carry on in the face of modest ticket sales. The businessman quite properly replied that very few, if any, dance groups made money but that he hadn’t supposed his friend had gone into it to get rich. The man was so dismayed at this verdict of the marketplace that he abandoned his passion forthwith.

But the principal infection that new-money trustees carry with them onto a board is called “corporatization.” The infection comes in many forms. One is commercialization, whether it’s the ascendancy of shops and restaurants in the calculus of institutional performance, or a university’s determination to flog its science faculty’s research products, or the near universal “branding” of great and proud institutions. Centralization is another guise, as essentially feudal structures are replaced by command structures with swim-or-sink performance guidelines. Still another is “consumer sovereignty,” as proudly traditional private schools, for example, are obliged to bend and break every ancient custom to suit student and parent demand. Another is a penchant for bold financial practices, such as the hedge-fund and other alternative investments that in the recent recession financially imperiled not a few well-endowed American universities, several in the Ivy League.

Critics of the corporatization infection seldom have any idea of what should be done about it. One can hardly blame them. It’s embedded in the culture and an assumed moral imperative of growth and competition. Yet every one of the problems (never mind the cultural issues) raised by corporatization demands unusual judgment from the people who hold the institution in trust for the public, and their employees. One sign of the strain in the system is the proliferation—in business schools, law schools, public-policy schools, and divinity schools—of courses in philanthropy and nonprofit management. The Third Sector is rallying to protect its turf, or maybe to negotiate its surrender. In either case, they have no one to do it with but the trustees—a.k.a. the top people.

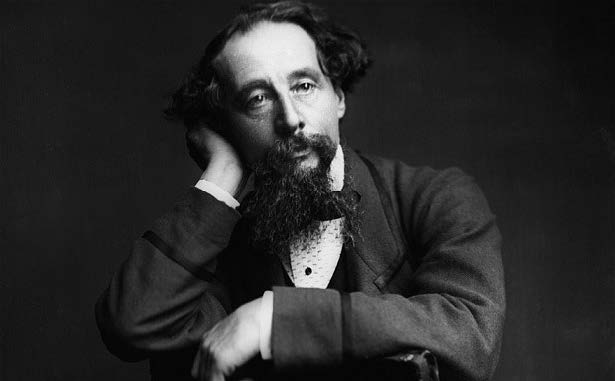

Bleak House

By Sandra Salmans

For Dickens, charity begins at home.

Should charity begin at home?

Yes, in the strong opinion of Charles Dickens, who used Mrs. Jellyby in Bleak House to blast what he termed “telescopic philanthropy.”

When we meet Mrs. Jellyby, she is busily engaged in dictating letters to her ink-stained wretch of a daughter on behalf of a project to settle some two hundred impoverished British families in Borrioboola-Gha, on the left bank of the Niger, where they are to cultivate coffee and educate the natives. Mrs. Jellyby’s home is squalid: Dinner is nearly raw and four envelopes float in the gravy, her innumerable children are virtually abandoned, and she herself is a mess—her hair needs brushing and her dress gapes in the back, revealing a lattice-work of stays “like a summer house.” But Mrs. Jellyby is blithely oblivious to the misery around her, the narrator writes; her handsome eyes “had a curious habit of seeming to look a long way off, as if . . . they could see nothing nearer than Africa.” When her oppressed daughter escapes her clutches to marry, the long-suffering Mr. Jellyby sends the girl off with one piece of advice: “Never have a mission.”

Like many of Dickens’ greatest characters—think Scrooge or Mr. Micawber or Miss Havisham—Mrs. Jellyby is regularly invoked by modern writers as a cautionary figure. Google “Mrs. Jellyby,” and you’ll see references on issues ranging from Gaza to coal mining. George Will accuses Arne Duncan, President Obama’s Secretary of Education, of a Jellyby-like indifference to the education of low-income children “within sight of his office” on Capitol Hill while pursuing loftier goals. Another writer, in a piece in Salon titled “Mrs. Jellyby Goes to Washington,” grumbles that the administration should focus on jobs, not global warming. A Christian scholar, arguing that Mrs. Jellyby and her like are motivated by anger, recalls an activist who nearly starved the office cat because he was morally opposed to the domestication of animals.

Mrs. Jellyby, drawn by Bill Cawley.

Mrs. Jellyby, drawn by Bill Cawley.But can we really learn from Mrs. Jellyby? Let’s remember that Dickens subscribed to the Victorian view that a woman’s place was in the home and was quick to condemn any woman who failed to be the “angel of the house.” (Never mind that Dickens himself was a less than exemplary husband and father.) It’s no accident that, at the end of Bleak House, Mrs. Jellyby, having discovered that her African king wanted to sell everybody— “who survived the climate”—for rum, takes up as her next cause the rights of women to sit in Parliament, a “mission” that Dickens evidently found as preposterous as Borrioboola.

While few charities are as ill-chosen as Mrs. Jellyby’s, philanthropy inevitably involves tradeoffs. Spending vast sums to fight AIDS in Africa can mean fewer funds for needy families closer to home; efforts to improve the conditions of the homeless here can result in less money for pre-school. Dollars, like time and energy, are finite. In the end, for philanthropists, the issue is arguably not how remote the cause but how deserving.

When West Meets East

By Wangsheng Li

The President of Hong Kong’s ZeShan Foundation speaks out.

When I heard Asia being described by Western observers as “philanthropy’s new frontier,” I cringed.

I couldn’t help but wonder how easy it was for otherwise intelligent and well-meaning commentators to overlook the long-standing tradition of charitable giving in Asian societies. Is it mere ignorance or a backward missionary mindset at work? A lack of cultural sensitivity? This calls to mind the lukewarm reception that the push for the Giving Pledge initiative received in Asia.

The conventional thinking is that organized philanthropy (as opposed to charitable deeds that respond to specific situations, without a formal structure) is an invention of Western civilization. Historians and academics may have fun debating that. However, that view has had a profound influence on both Euro-American philanthropy professionals and their counterparts in the rest of the world when it comes to the advancement of philanthropy.

Zeshan Foundation Logo

Zeshan Foundation Logo

As an Asian who was educated in the West and honed his philanthropic skills in the US, I draw a distinction between localization and indigenization in the context of advancement of philanthropy. The former places emphasis squarely on developing locale-specific knowledge to promote leadership and professional pipelines for the local philanthropic sector; the latter aspires to transplant well-established theories and practices to a setting that is foreign, be it geographically or culturally.

That is not to dismiss or undervalue the enormous body of knowledge and skills our Western counterparts have developed and perfected over the years. On the contrary, they have priceless instructive value that can inspire and provoke.

In the past half-century or so, we have witnessed a remarkable transition of missionary-driven charitable endeavors in the post-colonial era to mandate-guided institutionalized philanthropy. If charity is a natural product of human civilization, the practice of institutionalized philanthropy is an inevitable result of a (maturing) civil society. Philanthropy with “Asian characteristics” is playing an important transformational role in social development and political reform. While our Western counterparts relish “strategic philanthropy,” I’m chewing on “catalytic philanthropy.”

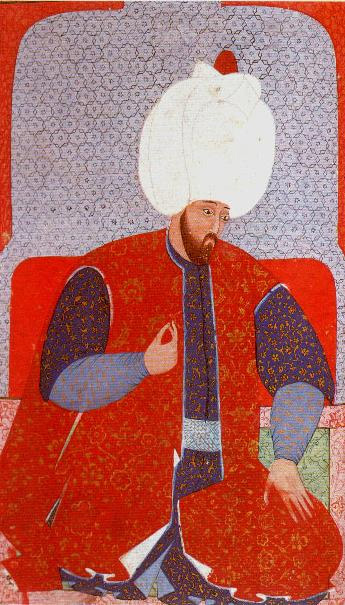

The Persistence of Philanthropy

By Amy Singer

One of the most profound Ottoman legacies to modern Turkey is a long history of private philanthropy.

I fell into the study of philanthropy while trying to make sense of rural taxation and land tenure in 16th century Palestine, then under Ottoman rule. Several weeks in the imperial archives of the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul brought me face-to-face with an exquisite series of long scrolls penned in gold, lapis, and black inks some five hundred years old. They recorded orders from Sultan Süleyman “the Magnificent” to transfer properties to his wife, Hurrem Sultan. From these she immediately created an endowment, a waqf, to support a public utility in the middle of Jerusalem, a space allocated for what we may now consider a soup kitchen, serving meals twice a day.