About

Global Team

Roberta d’Eustachio

Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Roberta d'Eustachio (Rd'E) is an entrepreneur obsessed with delivering media from the social investor/philanthropist's point of view. That desire led to founding The American Benefactor, the first consumer magazine for philanthropists, as well as Giving Magazine and each of its subsequent evolutions: from print, to digital, to mobile with Facebook Instant Articles, delivering stories of social impact - for everyone, everywhere.

Rd'E has consulted with, and/or received investment from, leading global brands, including: The Economist, the Financial Times, Euro Money/Institutional Investor, the Pitcairn Family Office, Fidelity Capital and the World Bank as well as philanthropists and social enterprises around the world.

After serving as chief-of-staff to Dame Stephanie Shirley, the British Government’s Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy, Rd'E founded the AmbassadorsForPhilanthropy.com enterprise to give social investors a voice worldwide.

Dame Stephanie Shirley

Philanthropist & Believer-in-chief

Dame Stephanie “Steve” Shirley is a British entrepreneur turned philanthropist. She originally arrived in London as an unaccompanied Kindertransport child refugee from Austria during WWII. “Steve” was an early pioneer in technology and, after taking her company public, she has given more than $100 million to organizations that specialize in autism research and technology, including founding the Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University. Appointed by Prime Minister Gordon Brown to the title of the British Government's Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy 2009-2010, she believes in the advancement of the philanthropist voice worldwide.

Her memoir “Let It Go” was recently published, chronicling her life so far.

"Steve" is the Believer-in-chief to Giving Magazine, providing the means to imagine and execute its potential to the fullest.

Jerry Alten

Chief Curator

Jerry Alten is a world-renowned art director of magazines, across all devices, and other marketing and advertising work, winning many prizes in the media field. Under Walter Annenberg’s ownership of TV Guide, Jerry took the circulation from 5 million up to 19 million during his tenure as art director. He continued to work with Rupert Murdoch’s organization after the buy out of TV Guide and created the first interactive website for the magazine. Jerry was also the original investor in The American Benefactor Magazine and art director, which succeeded in obtaining more than $7 million worth of investment from Fidelity Investment's venture firm.

Brian Lipscomb

Chief Technologist

Brian Lipscomb has been involved with technology for over twenty years, and founded technology services company Divergex, based in Philadelphia. Specializing in all aspects of computers, Brian brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to Giving Magazine. His philosophy is: “Do it right, or don’t do it at all.”

Lipscomb adds: “Technology is a constantly evolving industry. People who use technology daily don’t have the time to study and learn all of the new and different terms and capabilities. I work to show people how technology can improve their efficiency, productivity and, ultimately, their lives.”

Jay Balfour

Managing Editor

Before Jay became the Managing Editor for Giving, he was a freelance writer and editor based in Philadelphia. With an academic background in Philosophy he leverages an informed perspective on everything from African music to youth movements in the West for several publications both online and in print. At Giving Magazine he shares a passion for unabated reporting and the ushering in of a new age in philanthropy.

Sandra Salmans

Executive Editor

Sandra Salmans is a New york-based writer and editor who works primarily in the nonprofit field. She began her career as a business and financial journalist at Newsweek and The New York Times, but has also covered national news, education and the arts. Prior to going freelance, she was a senior officer in communications for a leading foundation in Philadelphia.

Nicole Raeder

Digital Design Manager

Nicole delights in great design. That's why her commitment is compulsive; contagious even, to get it right. Or, change it. Or, change it again. Whatever is required to finding the way to the end point, which is sometimes the beginning. In other words, she never gives up, or stops, till the thing clicks.

She also loves cats.

Damon d'Eustachio

Co-Director, Global Membership

A foodie who navigated his way from the city of brotherly love to Charleston, S.C, Damon is devoted to serving nonprofits worldwide that believe the philanthropist voice must be heard.

Damon graduated from the College of Charleston in Art Administration and performed an internship at London’s prestigious Tate Gallery’s New York City office.

Jessica Lambrakos

Co-Director, Global Membership

Jessica is responsible for the management and development of the Global Awards for nonprofits of Giving Magazine for their nominated philanthropists and supporters.

She also serves as founder and executive director of her own nonprofit, “The Naked Truth AIDS Project”, which raises funds for AIDS prevention education programs in the USA as well as Africa.

Nick Cater

Contributing Editor

Nick Cater is a UK-based international writer and editor. A former Fleet Street journalist, he has reported from more than 40 countries so far on stories as diverse as war in Africa, environmental risks in Latin America, disasters in Europe, and the Asian sport of elephant polo.

Luke Norman

Senior Editor

Luke Norman is an experienced journalist and corporate social responsibility consultant. Having started at The Daily Telegraph, Luke has worked for a wide range of international media outlets before moving into the heady world of multi-national corporations and their sustainability commitments. Luke has transplanted himself and his family from London to Rio de Janeiro, where the views he now observes are deliriously engaging.

Doug White

Senior Editor

Doug White, a long-time leader in the nation's philanthropic community, is an author, professor, and an advisor to nonprofit organizations and philanthropists. He is the director of Columbia University's Master of Science in Fundraising Management program. He also teaches board governance, ethics and fundraising. His most recent book, “Abusing Donor Intent,” chronicles the historic lawsuit brought against Princeton University by the children of Charles and Marie Robertson, the couple who donated $35 million in 1961 to endow the graduate program at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Kent Allen

Journalist

Kent Allen is a longtime daily journalist and freelance writer. Over the past 20 years, while also writing about philanthropy and nonprofits, he has worked as an editor at The Washington Post, U.S. News & World Report and Congressional Quarterly. At present, Kent is a journalism and history teacher at The Field School, a middle and high school in Washington, D.C.

Lucy Bernholz

Journalist

Lucy Bernholz is a blogger and self-proclaimed “philanthropy wonk”. Her blog, Philanthropy 2173: The future of good, has been named a “best blog” by Fast Company and a “philanthropy game changer” by the Huffington Post.

Kim Breslin

Actor

Kim Breslin is an actress, comedienne, director, producer, artist, and chef. She has been an educator in North Philadelphia for 17 Years. Mother of two incredible children, she lives with her highly supportive cat, The Amazing Sid.

Cheryl Chapman

Journalist

Cheryl Chapman actively promotes philanthropy in the UK and globally via her journalism. She was the editor of Philanthopy UK: Inspiring Giving and now heads City Philanthropy, London, as its Director.

Stephen Dunn

Poet

Stephen Dunn, Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, is the author of 11 collections of poems, including “Different Hours,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 2001.

Regan Good

Poet

Regan Good is a freelance writer and poet living in Brooklyn, New York. She has written for The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times Magazine and others. She is currently at work on a memoir about growing up in a family of writers.

Sharilyn Hale

Journalist

Sharilyn Hale, M.A., CFRE is Founder and Principal of Watermark Philanthropic Advising where she offers strategies for meaningful giving, receiving and leading. A practitioner, author and educator, she brings a global perspective on philanthropy having served the nonprofit sector across North America, Bermuda and the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. She holds a graduate degree in Philanthropy & Development and is past Chair of CFRE International, the global certification for professional fundraisers setting standards for ethical and accountable practices.

Crystal Hayling

Journalist

Believer in a better world. Uppity advocate for social change. Former philanthrapoid. Crystal lives in Singapore where she helps donors develop strategy for effective grantmaking. She serves on numerous boards, and is a speaker and writer on civil society. Twitter: chayling

Holly Howe

Journalist

Holly Howe is a strategic communications consultant with a particular focus on the arts. She works as a freelance journalist, writing for various publications including FAD, RWD, House (published by the Soho House group) and the Irish Examiner. She also runs the Culture Vultures, a networking group for people in media and the arts. She can be found tweeting at @ hollytorious and in her occasional spare moments, she posts on her blog www.postcardsfromholly.blogspot.com

Wangsheng Li

Journalist

Wangsheng Li is president of ZeShan Foundation (Hong Kong) and a Senior Fellow of the Synergos Institute (New York City).

Lisa Macdonald

Journalist

Lisa MacDonald is a freelance writer and editor based in Toronto. A passion for philanthropy drives her involvement in initiatives that bring information and innovative ideas to Canada’s nonprofit sector leaders. Tweet her at @lisalmacdonald.

Andrew MacLarty

Actor

Andrew MacLarty is a New York based actor who has appeared on Boardwalk Empire and White Collar. Non-profit work includes narration for Partnership for a Drug-Free America, performances at the United Nations for Hurricane Katrina relief benefit shows, and Barefoot Theater Company’s ROCKAWAY benefit for Hurricane Sandy victims.

Bruce Makous

Journalist

Bruce Makous, ChFC, CAP, CFRE, has been a professional fundraiser for over twenty-seven years, with leadership positions in major educational, healthcare, and arts organizations. In 2009, he was named by the Nonprofit Times one of the “Most Influential and Effective” fundraisers in the US.

Peter D. Michael

Actor

For over 20 years, Peter D. Michael has been an established actor, voiceover talent and stand-up comedian. He is also an Emmy award winner.

Suzanne Reisman

Journalist

Suzanne is a U.S. international private client lawyer based in London. Suzanne assists philanthropists, their foundations, and international charities with cross-border philanthropy.

Julie Shafer

Journalist

Founder of Julie Shafer Development + Philanthropy, a national philanthropy consulting firm. Ms. Shafer offers a multifaceted skill set honed throughout 20 years as a philanthropy executive bringing a translational approach that bridges the gaps between philanthropists and non-profits.

Jade Shames

Playwright

Jade Shames is an award-winning writer living in Brooklyn, NY. His work can be found in The Best American Poetry blog, The LA Weekly, HOW art and literary journal, and more. He was awarded a creative writing scholarship to attend The New School where he received his MFA.

Amy Singer

Journalist

Amy Singer teaches Ottoman and Turkish history, as well as courses on Islamic philanthropy and the history of charity in the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University. Her recent publications include the book "Charity in Islamic Societies", and in 2008 she was awarded the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Award.

Sharit Tarabay

Artist

Sharit Tarabay painted the portrait of Gerry Lenfest. He is a painter and illustrator living in Montreal. He has his works published in magazines and books around the world.

James V. Toscano

Journalist

Jim Toscano is a principal in the consulting firm, Toscano Advisors, LLC, and an adjunct professor at the School of Business, Hamline University. Recently retired as president of the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, the cardiovascular research and education center of Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, he is a past chair of the Minnesota Charities Review Council and board member of Minnesota Council of Nonprofits.

Susan Yu

Journalist

Susan Yu is a journalist from the San Francisco Bay Area. She is an award-winning news reporter who was formerly based in Hong Kong for 14 years covering stories in Asia for international news media organisations. She is currently based in the United Kingdom where she freelances as a writer, editor and documentary film producer.

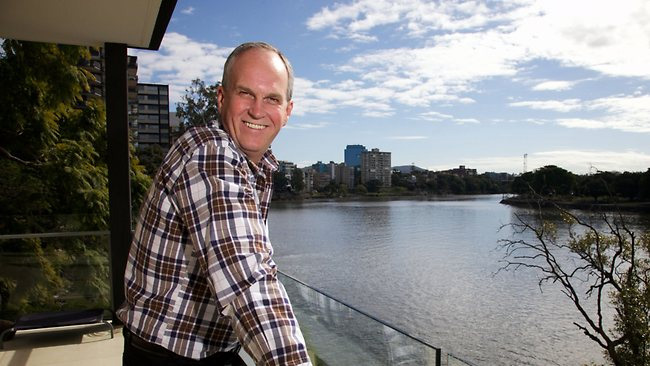

Clare Brooks

By Clare Brooks

Brought down under to lead the Australia Communities Foundation, Brooks shares what she calls her "marvelous adventure."

“The Australian countryside looks so . . . so . . . savage,” my Melbourne host told me. That wasn’t her view of course; she was quoting a British visitor.

Did I think the same? No, I reassured her. Quite the opposite, I found it marvelous.

Terra Australis has a beauty, complexity and originality that are breathtaking and intoxicating. I’d heard of the uniqueness of its wildlife but it’s hard to imagine how larger-than-life Australia is until you’ve stepped off the plane. It has giant landscapes, skies, wilderness, and belief systems; the Australian Aboriginal culture is the oldest maintained culture on the planet.

It also has a unique culture of giving. Charities Aid Foundation (CAF), a nonprofit organization that conducts research on international giving trends, ranked Australia first in its 2012 World Giving Index as a function of the public’s open-handedness in times of need. CAF’s Index is far from a measure on purely financial terms—it includes categories for volunteering time and “helping strangers”— but its findings do reflect Australia’s generosity.

The country has its pantheon of philanthropists, many of them with connections to the state of Victoria, home to Melbourne and 80 percent of the country’s charitable trusts. (Victoria is Australia’s most densely populated state.) Still, most Australians are almost vehemently self-effacing about their giving, even if some are beginning to understand that they can better further the causes they care about if they go public.

Dame Elizabeth Murdoch, mother of media tycoon Rupert, was particularly admired for her giving and her personal involvement in the charities she supported, and she was universally mourned upon her death in 2012. The country’s charitable landscape is dotted with other venerable (for a young country) family names, like Potter, Myer, Felton and Holmes à Court. And new names in philanthropy are springing up, the result of an economy that boomed in 1990s and weathered the recent global recession.

But while charitable donations are at record levels, some critics complain that the increase simply reflects the economic boom, and that the proportion of those giving has been flat, at 50 percent. Some Australians are calling for more streamlined charity legislation and more transparent and accountable philanthropic practices. In more than one way the country has shown a commitment to push the philanthropic needle even farther.

To encourage leadership, for example, the state of Queensland holds an annual Philanthropist Awards ceremony. Recently a partnership of charitable organizations launched the publication of Australia’s 50 Top Philanthropic Gifts of All Time. The list, which goes back to the 1800s, makes fascinating reading and isn’t exclusive to the mega-wealthy. It invited the public to vote online for Australia’s Top 10 Gifts. I never said Australians weren’t competitive.

The Australian Communities Foundation, an organization I had the good fortune to be associated with during my time down under, also proved to me that mateship and the idea of a fair go aren’t just Australian cultural myths but realities. In the charitable world, they lend themselves to a host of very democratic and often sociable donor-advised funds and Gumnut Accounts, which donors can open for a few dollars a day.

Alongside growing gifts of cash, there is also some epic social entrepreneurism. One venture that began in Australia but has now gone global is Movember, the mustache-themed awareness month that aims to “change the face of men’s health.” It began with some mates having a pint in a pub.

See what I mean? Jokes over a few beers raise 1.1 million new Mo’s and around $100 million across the globe for charity. Marvelous!

Andrew Forrest

By Chris Hornsey

“If you give, let people know,” says Australia’s first Giving Pledger.

Much about Andrew Forrest is larger than life. “Twiggy”—the boyhood nickname by which Forrest is still known throughout Australia—is one of the richest men on the continent thanks to his no-holds-barred approach to business, which is currently profiting handsomely from China’s insatiable appetite for iron ore. At the same time, he has fast become one of the most generous Australians ever, giving away tens of millions of dollars in a short span and, in 2013, cosigning with his wife, Nicola, the Giving Pledge, with a promise to donate “the vast majority of our wealth” to benefit “those less fortunate, within our lifetime or at our death.”

“Wealthy people in Australia tend to give, and give very quietly,” Forrest recently said in an interview with the national radio station ABC Radio. “That is wonderful that they do that, but if they actually give and let people know, it acts as an inspiration.” In fact, a few years ago Forrest, now 52, stepped down as chief executive officer of Fortescue Metal Group (FMG), his mining behemoth, because he was devoting more than half his time to philanthropy, he said.

Although they are newcomers to the Giving Pledge, the Forrests’ commitment to helping native Australians has some history. In 2001, with a contribution of more than $90 million in company shares, they established the Australian Children’s Trust (ACT) to assist underprivileged youth. ACT’s first annual report, published in 2011-12, highlights the Forrest family’s donation of $260 million to charitable causes “committed to ending indigenous disparity, improving the lives of disadvantaged Australians, supporting the arts and education, and ending modern slavery around the world.” The Forrests also partner with other wealthy Australian entrepreneurs in underwriting projects aimed at educating, training, mentoring and employing indigenous Australians.

Separately Fortescue Metals launched the Billion Opportunities program, which set a goal of awarding $1 billion in contracts and subcontracts to Aboriginal businesses by the end of 2013. The company said it met the target ahead of schedule. Writing in Sydney’s Telegraph newspaper, Forrest himself applauded the initiative with an acknowledgement that granting Australia’s Aboriginal communities with such employment opportunities represents a shared path forward. “I’m asking governments, Aboriginal elders and businesses all to take the history-making example of Billion Opportunities and lead us all out of welfare and out of indigenous disparity,” he declared.

More recently, Forrest announced a donation of $65 million for higher education in his home state of Western Australia. According to Philanthropy Australia, which charts the country’s charitable industry, the 2013 gift was the largest of its kind in Australian history, and, as a high profile donation, it was typically Twiggy. The money will go towards a $50 million scholarship foundation for the state’s five universities and a new residential college at the University of WA.

While the Forrests’ generosity is often celebrated in Australia, critics have also questioned their philanthropy as well as the business deals that make it possible. Years ago, many Australians rallied against his falling far short of his promised delivery of relief housing to communities devastated by fatal bushfires in Victoria in 2009. Many laud the assistance while others have remained critical of his high-handed approach in dealings with indigenous communities. Early in 2014, Forrest released a review of Indigenous Employment and Training commissioned by the Australian government and has since attracted widespread criticism for his campaign to instate a cashless welfare system that would bar recipients from purchasing restricted items.

Separately, a profile published in 2013 by The Monthly, an Australian political and cultural magazine, canvassed his investments, philosophy, and philanthropy with a report that noted that “while Forrest’s $90 million in Australian Children’s Trust donations was ‘the largest exercise in philanthropy in Australian history,’ tax benefits (and some coincidental slumps in share prices) meant his true net loss was ‘probably less than $2 million.’” And a new, unauthorized biography chronicles Twiggy’s bare-knuckles approach to business deals and, in court, a casual relationship to the truth.

In that context, Forrest’s Giving Pledge letter is particularly revealing. “Australians cherish the right to accumulate capital and distribute it any way they feel,” he wrote. It may be that very attitude that lets Twiggy lead by example. Generosity “is at the absolute heart of being Australian,” said social analyst David Chalke. For Forrest, he continued, “it’s not so much giving but the encouragement of giving that is important.”

Allan English

By Doug White

Allan English wants to microfinance a million people out of poverty by 2020. How's he doing?

You never know what a gift solicitation will lead to.

By the early 2000s, Allan English had achieved a good deal of success with Silver Chef, a firm he founded in 1985. Around that time, he responded to a request for $10,000 from Opportunity International. He’d had no history with the charity, but its work struck a chord with him. Specifically, he was asked to support a micro-finance center in East Timor.

The idea for Silver Chef came from a trade show in the United States. The American home delivery pizza market was booming, and English saw the market’s potential in Australia. Soon after he invested heavily in conveyor ovens, however, he discovered that many small pizza operations couldn’t afford to buy them. So he decided to rent them out and, pretty soon, when the pizza store owners began generating revenue, they began to buy the ovens. Ten years later, Allan devised a funding option that enabled small businesses to procure the equipment they needed without committing large amounts of capital up-front. It’s called and trademarked as Rent-Try-Buy.

As a moderately wealthy man and as an occasional donor, he was looking around for ways to do something significant. “The idea of owning big boats and big houses didn’t do it for me," he says. When English saw a request from Opportunity International and their outlined cause, he recruited as many friends as he could to the cause. “And away we went,” he says. Then, about a month later, “I was catching a glass of red and I received a report from Opportunity International that explained the impact we were making. The forecast was that 40,000 lives were going to be changed over the next five years because of the project we were supporting.”

And that’s when it happened: “It just hit me like a rock. Forty thousand people—that’s a football stadium full of people. And there was no ego attached to this. It was absolutely pure impact. Imagine doing that every year. Wouldn’t that be fun?”

He decided it would be. “Now I had a purpose to go back to work and create wealth. So I hired someone to take over my volunteering stuff and I went back to work.” After he returned, the company grew 600 percent over the following six years. And in 2005 the company went public on the Australian Stock Exchange.

Then he set up his own family foundation. Endowed with $20 million in Silver Chef shares, the foundation distributes about $1 million annually. Forty percent is earmarked for poverty-alleviation programs overseas. “We have a very audacious goal to fund one million people out of poverty by the year 2020. So far we’re at 200,000 and we’re on our way.” Another 40 percent is distributed in Southeast Queensland and the remaining 20 percent is in a social innovation fund for, as English puts it, “young people with vibrant ideas.” He senses that he’s “not in a sexy space" by his own admission: "I don’t go for puppy dogs and kids’ charities—I tend to go for the things that are a bit tougher in our community, which probably sometimes get ignored.

“It’s my journey from success to significance," he adds. "From financial success in a business sense to having more significance in my life because of the work that we are doing.”

The Community Foundation

By Sandra Salmans

How a hundred-year-old idea is reshaping philanthropy around the world.

Carnegie and Rockefeller had recently established—and lavishly endowed—their eponymous foundations when Frederick Goff, president of the Cleveland Trust Company, had a different idea: a “community trust” to which the city’s philanthropists could all contribute. Interest on the money, it was declared, would fund “such charitable purposes as will best make for the mental, moral, and physical improvement of the inhabitants of Cleveland.”

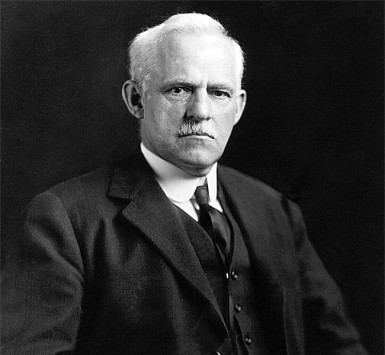

Frederick-Goff

Frederick-GoffThus, 100 years ago, was born the world’s first community foundation. (Bequests were, not coincidentally, deposited at the Cleveland Trust Company—setting a precedent for the charitable funds later established by financial services companies such as Fidelity, Schwab and Vanguard.) The Cleveland Foundation was soon leaving its mark on the city, supporting the creation of the so-called “emerald necklace” of the city’s parks, shaking up the corrupt judicial system, spearheading public school reforms that included equal education opportunities for girls. And within five years, community foundations (CFs) had sprung up in Chicago, Boston, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Buffalo, NY.

The growth of CFs since then has been immense, immeasurably greater than even the visionary Goff could have dreamed. Today there are an estimated 700 CFs in the US. According to CF Insights, a consultancy specializing in community foundations, assets at CFs in the U.S. totaled $66 billion in 2013, an increase of $8 billion over the previous year. The Silicon Valley Community Foundation (SVCF) led the way, at $4.7 billion, followed by the Tulsa Community Foundation, with $3.9 billion, and the New York Community Trust, with $2.4 billion. (SVCF’s assets, which ballooned with a $1 billion gift from Mark Zuckerberg in 2013, surged ahead again in 2014 with a $500 million stake in the camera maker GoPro from its founders.)

Mark Zuckerberg

Mark ZuckerbergIn 2013, commemorating the 100 years since the first CF was established, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation created a chair on community foundations at Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. And this past October, to celebrate the centenary of the CF, the Council on Foundations gathered leading philanthropic organizations in Cleveland, where it all began.

What’s more, the rest of the world—including the developing world—is rapidly following America’s lead. According to the latest tally by WINGS (Worldwide Initiatives for Grantmaker Support), a global network of grantmaker support organizations, and the Community Fund Atlas, which is underwritten by the Cleveland Foundation, there are currently some 1,100 CFs outside the US, in more than 50 countries and on six continents. Having launched in the US and Canada in 1914, the CF crossed the Atlantic to Britain about 35 years ago, took root in Germany around the time of reunification, spread to Russia and the former Soviet states, and is currently establishing a foothold throughout the developing world. Between 2010 and 2014, eight new CFs were established in Asia-Pacific, four in sub-Saharan Africa, four in Latin America and two in the Middle East. As the Mott Foundation aptly declared in its 2012 annual report, CFs are “rooted locally, growing globally.”

Whether in the industrialized world or the emerging one, CFs are identical in one key respect: They are public charities that tap the wealth of their communities, with the goal of redistributing it locally. That mission has universal application, asserts Emmett Carson, who is the SVCF’s chief executive officer and is also the visiting holder of the new Mott chair on community foundations. “We should think of the community foundation concept like water,” he says. “The water is the same, but it takes on the shape of whatever community you pour it into.”

Emmett Carson

Emmett CarsonAnd the fact is that CFs differ markedly from one country to another—and, increasingly, even within a country. In the developed world, many CFs are taking on a more activist role than in the past, initiating projects and partnerships as well as donating to established programs. What’s more, many are traveling far beyond their borders, accepting funds from a wider audience and playing a role on the national and even international stage

Meanwhile, the CFs that are springing up in less developed areas—Africa, Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe—are digging deep into their communities to convince residents to trust the very concept of pooling and distributing funds. While endowments and professional leadership are the hallmarks of long-standing CFs in the US, money necessarily takes a back seat to other priorities among CFs in emerging countries, where there are only small pockets of wealth. “They have to prove they’re relevant to the community and need to establish trust where often there are low levels of trust,” notes Nick Deychakiwsky, program officer for the Mott Foundation’s civil society team. In fact, in many cases those CFs have received a jumpstart by foundations such as Mott, Ford, Open Society and Aga Khan, and also appeal to the diaspora for funds.

Nick Deychakiwsky

Nick DeychakiwskyAs Jenny Hodgson, director of the South Africa-based Global Fund for Community Foundations, observes, community philanthropy is as old as, well, communities themselves. “Every country and culture has its traditions of giving and mutual support between family, friends and neighbors,” she has written, pointing to the tradition of burial societies across Africa and hometown associations in Mexico.

However, the new generation of community philanthropy institutions—fueled by factors ranging from a growing concentration of wealth to the popularity of social media, according to WINGS executive director Helena Monteiro—take a more strategic approach to giving. “Most are about development rather than donor services, and they do a lot of capacity building,” Hodgson told Giving. “They’re building civil society, essentially.” As the Kenya Community Development Foundation, a CF established in 1997, asserts on its website, its goal is “the growth and sustainability of communities by their strong engagement in owning and driving their development efforts.” (Italics are KCDF’s.)

Helena Monteiro

Helena MonteiroA sampling of this new breed of CFs offers a glimpse of the variety of programs being undertaken:

- In Egypt, the Community Foundation for South Sinai is working to support the Bedouin, who have long been marginalized. The CF is working on several fronts to raise the tribes out of poverty and preserve their heritage; projects have included teaching the women how to make useful wool products, and providing a camel to a boy who was his family’s breadwinner.

- In Costa Rica, the Monteverde Community Fund, initially founded to invest tourism revenue in preserving the rain forests, has added a social portfolio. Among other projects, it is promoting a community Internet-based radio station, training local youth to create programming and encouraging them to engage in public discourse.

- In Romania, multiple CFs have organized annual “swimathons” to raise their profiles, garner funds and spread the ethos of sharing. In Cluj, the country’s second most populous city, revenue went to support new programs for young people, including a robotics class in an elementary school and education for students with special needs.

- On the West Bank, the Dalia Association, a Palestinian CF, gave women from nearby villages $6,000 to build a park. The women went on to secure additional donations, including the land, utility hookups, a basketball court, a playground and a library.

- In Slovakia, the Banska Bystrica City Foundation—Eastern Europe’s oldest CF, initially launched as a World Health Organization project—has assembled a group of local donors that assist the city’s street children, provide support for the local Roma community, and encourage younger people to take an interest in philanthropy.

While all these CFs have struggled to raise money, elsewhere they have also encountered tight governmental controls or opposition. Even there, however, they are making headway. According to a recent report by CAF (Charities Aid Foundation) Russia, a support group for charitable and nonprofit groups, nearly two-thirds of the membership of CF governing boards comes from the authorities and business; even so, starting with one CF in 1998, Russia today has more than 45 community foundations. The situation is more problematic in China, where very few private organizations are permitted to do fundraising, grantmaking is relatively unknown and civil society is weak. Still, says Hodgson, “everybody is talking about community foundations in China. There’s lots of energy right now.”

That’s also an apt description of the situation in the US, where the biggest CFs are stepping up their game. Rather than limiting themselves to making grants to established programs, “community foundations are increasingly moving into the sphere of brokers for community solutions,” declares Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker, who heads the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo in New York State. Dedecker’s group was the prime mover in launching Say Yes to Education, an initiative that has brought together school parents, union leaders, the business sector and other stakeholders to provide year-round support to students K-12, including college scholarships.

Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker

Clotilde Perez-Bode DedeckerArguably the most striking example of the supercharged CF is the Silicon Valley Community Foundation. The result of a merger of two leading CFs in 2006, SVCF is not only the largest single grantmaker to Bay Area nonprofits, it’s the fifteenth largest international grantmaker in the United States, according to Carson. Furthermore, while SVCF draws much of its wealth from the affluent high-tech community, it also has donors who neither live in the Bay Area nor give to it, but choose to use SVCF as the means to distribute their philanthropy.

To Carson and others, these developments represent a natural progression for CFs in a society that is ever more global. “People increasingly see themselves as national citizens and, more likely, as global citizens,” he notes.” And because many Americans, or at least their parents, hail from different countries, they want to be able to send money overseas as well as to contribute to their new homelands. To compete in this arena—and also to counter the inroads made by financial services companies such as Vanguard and Fidelity, which are vying for donor-advised funds—the leading community foundations are carving out a niche in international philanthropy.

To some people in the CF world, venturing so far afield seems incompatible with the very notion of a community foundation. “A part of me says, ‘Shouldn’t it all be local?’” says the Mott’s Nick Deychakiwsky. But as someone with his own strong spiritual ties to Ukraine, Deychakiwsky concedes that “we’re all living in a more globalized world.” Ultimately, he hopes, globalization will lead to US-based CFs becoming more involved with community foundations abroad—relationships that could benefit organizations in both the developed and developing world. (And there are surprising similarities: Experts notes that CFs in emerging countries have a lot in common with those in rural areas of the US such as the deep South, where “hyperlocal” community development remains the sole focus.) “It’s amazing how much is transferable,” agrees Dedecker of the Community Foundation of Greater Buffalo, who is exploring the sharing of best practices with a CF in Nottingham, England. “The universal drive is for significant change and a strong sense of place,” she concludes. “That’s what unites us all.”

The Anonymist

By Sandra Salmans

Once the masked marvel of anonymous giving, Chuck Feeney now preaches the gospel of “giving while living.”

At one time, Chuck Feeney would have done everything in his power to keep his name out of this article—and off this site. He was so completely committed to his brand of covert philanthropy that beneficiaries were warned that his gifts would be snatched back if they revealed the source; funds were conveyed so clandestinely that some university dons fretted they’d be suspected of receiving laundered money. Yet his contributions were so large that when, inevitably, word of his magnanimity began to leak out, many in the philanthropic community automatically assumed that every “anonymous donor” was Chuck Feeney.

And, in many cases, they were right. Although the ranks of anonymous donors are, by definition, unnumbered, Feeney has surely been among the most generous. Over the past 30 years, he has given billions of dollars through his foundation, Atlantic Philanthropies, to a wide range of causes, starting with his alma mater, Cornell University, spreading to the entire university system in Ireland—and to the peace process in Northern Ireland—and more recently encompassing large-scale projects in education, science, health care, and other areas in Vietnam, South Africa, and Australia as well as the United States. In 1997, when a business transaction finally outed him, Time declared, “Feeney’s beneficence already ranks among the grandest of any living American.”

But in the past 17 years, having been forced to shed his cloak of invisibility, Feeney has become an eloquent—if still low-key—spokesman for philanthropy, and specifically for “giving while living.” In 2011 he signed the Giving Pledge launched by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett to encourage initially only the wealthiest Americans to commit to giving the majority of their wealth to good works either during their lifetime or after their death. (Feeney chose the first option, and Atlantic Philanthropies is slated to spend down its assets and go out of business by 2016.) He has allowed the press to tag along on his visits to donees; expounded on his views in a one-hour documentary about himself; cooperated in a biography, “The Billionaire Who Wasn’t,” by Irish journalist Conor O’Clery; and accepted honorary degrees and other recognition, including induction into the Irish American Hall of Fame. He has even released previous beneficiaries from their vow of silence. “The idea of anonymous giving was good, but eventually we became synonymous with anonymous,” Feeney told O’Clery. “It became evident we were kidding ourselves.”

All this amounts to a transformation for a man whom Forbes once called “the James Bond of philanthropy.” In his biography, however, Feeney notes one constant: “I had one idea that never changed in my mind—that you should use your wealth to help people.”

Although he is a modest celebrity today, at least in philanthropic circles, Feeney is unchanged in other respects, too. He remains a deeply private person, spurning the displays of wealth he could easily afford in favor of a simpler life that includes off-the-rack suits, $15 watches, and economy-class plane tickets to visit Atlantic beneficiaries. While he thrives on competition, money, for him, is just a means of keeping score. Growing up in blue-collar New Jersey, Feeney won a scholarship to the Cornell School of Hotel Management and then—through a combination of luck, street smarts, and sheer hubris—embarked on a business selling cars, perfume, and liquor to U.S. servicemen and tourists in Europe. That experience led to the founding of Duty Free Shoppers (DFS), a chain of airport shops that, capitalizing on a surge in international tourism, were an almost immediate success. But because DFS was privately owned by Feeney and three partners, it satisfied his penchant for secrecy. One reason Feeney was able to fly under the radar for so long was that the source of his fortune—as well as its uses—went undisclosed for years. In 1984, he transferred his sizable DFS stake to Atlantic. It wasn’t until he sold Atlantic’s DFS shares to a publicly-traded company in 1997 that Feeney’s cover was blown—and, with that, his curious identity as the world’s leading anonymous donor.

Those who know Feeney—and many more who don’t—have struggled to explain his obsession with secrecy, particularly when it comes to giving. Feeney likes to recount the story about his mother, a nurse, who used to jump into her car to pick up a disabled neighbor as he struggled to walk to the bus stop, insisting that she was going his way. Some family members have suggested that he became used to operating covertly in his intelligence work during the Korean War, a pattern reinforced when he was growing DFS without stirring up the competition. Still others point out that Feeney insisted on a low profile when he and his family—which ultimately included five children—lived in Europe during the 1970s, a time when criminal and political gangs over the border in Italy frequently kidnapped wealthy children for ransom. Feeney has also said that he did not want to be besieged by requests for donations, or to discourage other contributors from giving to a worthy cause.

Then there’s the critical role played by Harvey Dale, a Harvard Law professor and founding president of Atlantic Philanthropies, whom Feeney has described as the most influential person in his life. It was Dale who introduced Feeney to the writings of Maimonides, the 12th-century Jewish philosopher who said that it was best if the giver and receiver didn’t know each other, and Dale who pointed out that anonymous giving was favored in both the Sermon on the Mount and the Koran. Dale also urged Andrew Carnegie’s essay, “Wealth,” on Feeney, who has distributed copies to family and friends. Although Feeney resisted Carnegie’s lavish lifestyle, he responded to the steel magnate’s view that the rich had an obligation to use their assets responsibly to help others.

Feeney will be 85 when Atlantic Philanthropies allocates its last grants in 2016. At that time, he can probably—and gratefully—embrace a less visible lifestyle. But his name is inscribed among the world’s great philanthropists. He is Anonymous Donor no more.