About

Global Team

Roberta d’Eustachio

Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Roberta d'Eustachio (Rd'E) is an entrepreneur obsessed with delivering media from the social investor/philanthropist's point of view. That desire led to founding The American Benefactor, the first consumer magazine for philanthropists, as well as Giving Magazine and each of its subsequent evolutions: from print, to digital, to mobile with Facebook Instant Articles, delivering stories of social impact - for everyone, everywhere.

Rd'E has consulted with, and/or received investment from, leading global brands, including: The Economist, the Financial Times, Euro Money/Institutional Investor, the Pitcairn Family Office, Fidelity Capital and the World Bank as well as philanthropists and social enterprises around the world.

After serving as chief-of-staff to Dame Stephanie Shirley, the British Government’s Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy, Rd'E founded the AmbassadorsForPhilanthropy.com enterprise to give social investors a voice worldwide.

Dame Stephanie Shirley

Philanthropist & Believer-in-chief

Dame Stephanie “Steve” Shirley is a British entrepreneur turned philanthropist. She originally arrived in London as an unaccompanied Kindertransport child refugee from Austria during WWII. “Steve” was an early pioneer in technology and, after taking her company public, she has given more than $100 million to organizations that specialize in autism research and technology, including founding the Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University. Appointed by Prime Minister Gordon Brown to the title of the British Government's Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy 2009-2010, she believes in the advancement of the philanthropist voice worldwide.

Her memoir “Let It Go” was recently published, chronicling her life so far.

"Steve" is the Believer-in-chief to Giving Magazine, providing the means to imagine and execute its potential to the fullest.

Jerry Alten

Chief Curator

Jerry Alten is a world-renowned art director of magazines, across all devices, and other marketing and advertising work, winning many prizes in the media field. Under Walter Annenberg’s ownership of TV Guide, Jerry took the circulation from 5 million up to 19 million during his tenure as art director. He continued to work with Rupert Murdoch’s organization after the buy out of TV Guide and created the first interactive website for the magazine. Jerry was also the original investor in The American Benefactor Magazine and art director, which succeeded in obtaining more than $7 million worth of investment from Fidelity Investment's venture firm.

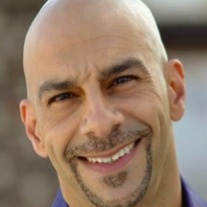

Brian Lipscomb

Chief Technologist

Brian Lipscomb has been involved with technology for over twenty years, and founded technology services company Divergex, based in Philadelphia. Specializing in all aspects of computers, Brian brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to Giving Magazine. His philosophy is: “Do it right, or don’t do it at all.”

Lipscomb adds: “Technology is a constantly evolving industry. People who use technology daily don’t have the time to study and learn all of the new and different terms and capabilities. I work to show people how technology can improve their efficiency, productivity and, ultimately, their lives.”

Jay Balfour

Managing Editor

Before Jay became the Managing Editor for Giving, he was a freelance writer and editor based in Philadelphia. With an academic background in Philosophy he leverages an informed perspective on everything from African music to youth movements in the West for several publications both online and in print. At Giving Magazine he shares a passion for unabated reporting and the ushering in of a new age in philanthropy.

Sandra Salmans

Executive Editor

Sandra Salmans is a New york-based writer and editor who works primarily in the nonprofit field. She began her career as a business and financial journalist at Newsweek and The New York Times, but has also covered national news, education and the arts. Prior to going freelance, she was a senior officer in communications for a leading foundation in Philadelphia.

Nicole Raeder

Digital Design Manager

Nicole delights in great design. That's why her commitment is compulsive; contagious even, to get it right. Or, change it. Or, change it again. Whatever is required to finding the way to the end point, which is sometimes the beginning. In other words, she never gives up, or stops, till the thing clicks.

She also loves cats.

Damon d'Eustachio

Co-Director, Global Membership

A foodie who navigated his way from the city of brotherly love to Charleston, S.C, Damon is devoted to serving nonprofits worldwide that believe the philanthropist voice must be heard.

Damon graduated from the College of Charleston in Art Administration and performed an internship at London’s prestigious Tate Gallery’s New York City office.

Jessica Lambrakos

Co-Director, Global Membership

Jessica is responsible for the management and development of the Global Awards for nonprofits of Giving Magazine for their nominated philanthropists and supporters.

She also serves as founder and executive director of her own nonprofit, “The Naked Truth AIDS Project”, which raises funds for AIDS prevention education programs in the USA as well as Africa.

Nick Cater

Contributing Editor

Nick Cater is a UK-based international writer and editor. A former Fleet Street journalist, he has reported from more than 40 countries so far on stories as diverse as war in Africa, environmental risks in Latin America, disasters in Europe, and the Asian sport of elephant polo.

Luke Norman

Senior Editor

Luke Norman is an experienced journalist and corporate social responsibility consultant. Having started at The Daily Telegraph, Luke has worked for a wide range of international media outlets before moving into the heady world of multi-national corporations and their sustainability commitments. Luke has transplanted himself and his family from London to Rio de Janeiro, where the views he now observes are deliriously engaging.

Doug White

Senior Editor

Doug White, a long-time leader in the nation's philanthropic community, is an author, professor, and an advisor to nonprofit organizations and philanthropists. He is the director of Columbia University's Master of Science in Fundraising Management program. He also teaches board governance, ethics and fundraising. His most recent book, “Abusing Donor Intent,” chronicles the historic lawsuit brought against Princeton University by the children of Charles and Marie Robertson, the couple who donated $35 million in 1961 to endow the graduate program at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Kent Allen

Journalist

Kent Allen is a longtime daily journalist and freelance writer. Over the past 20 years, while also writing about philanthropy and nonprofits, he has worked as an editor at The Washington Post, U.S. News & World Report and Congressional Quarterly. At present, Kent is a journalism and history teacher at The Field School, a middle and high school in Washington, D.C.

Lucy Bernholz

Journalist

Lucy Bernholz is a blogger and self-proclaimed “philanthropy wonk”. Her blog, Philanthropy 2173: The future of good, has been named a “best blog” by Fast Company and a “philanthropy game changer” by the Huffington Post.

Kim Breslin

Actor

Kim Breslin is an actress, comedienne, director, producer, artist, and chef. She has been an educator in North Philadelphia for 17 Years. Mother of two incredible children, she lives with her highly supportive cat, The Amazing Sid.

Cheryl Chapman

Journalist

Cheryl Chapman actively promotes philanthropy in the UK and globally via her journalism. She was the editor of Philanthopy UK: Inspiring Giving and now heads City Philanthropy, London, as its Director.

Stephen Dunn

Poet

Stephen Dunn, Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, is the author of 11 collections of poems, including “Different Hours,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 2001.

Regan Good

Poet

Regan Good is a freelance writer and poet living in Brooklyn, New York. She has written for The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times Magazine and others. She is currently at work on a memoir about growing up in a family of writers.

Sharilyn Hale

Journalist

Sharilyn Hale, M.A., CFRE is Founder and Principal of Watermark Philanthropic Advising where she offers strategies for meaningful giving, receiving and leading. A practitioner, author and educator, she brings a global perspective on philanthropy having served the nonprofit sector across North America, Bermuda and the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. She holds a graduate degree in Philanthropy & Development and is past Chair of CFRE International, the global certification for professional fundraisers setting standards for ethical and accountable practices.

Crystal Hayling

Journalist

Believer in a better world. Uppity advocate for social change. Former philanthrapoid. Crystal lives in Singapore where she helps donors develop strategy for effective grantmaking. She serves on numerous boards, and is a speaker and writer on civil society. Twitter: chayling

Holly Howe

Journalist

Holly Howe is a strategic communications consultant with a particular focus on the arts. She works as a freelance journalist, writing for various publications including FAD, RWD, House (published by the Soho House group) and the Irish Examiner. She also runs the Culture Vultures, a networking group for people in media and the arts. She can be found tweeting at @ hollytorious and in her occasional spare moments, she posts on her blog www.postcardsfromholly.blogspot.com

Wangsheng Li

Journalist

Wangsheng Li is president of ZeShan Foundation (Hong Kong) and a Senior Fellow of the Synergos Institute (New York City).

Lisa Macdonald

Journalist

Lisa MacDonald is a freelance writer and editor based in Toronto. A passion for philanthropy drives her involvement in initiatives that bring information and innovative ideas to Canada’s nonprofit sector leaders. Tweet her at @lisalmacdonald.

Andrew MacLarty

Actor

Andrew MacLarty is a New York based actor who has appeared on Boardwalk Empire and White Collar. Non-profit work includes narration for Partnership for a Drug-Free America, performances at the United Nations for Hurricane Katrina relief benefit shows, and Barefoot Theater Company’s ROCKAWAY benefit for Hurricane Sandy victims.

Bruce Makous

Journalist

Bruce Makous, ChFC, CAP, CFRE, has been a professional fundraiser for over twenty-seven years, with leadership positions in major educational, healthcare, and arts organizations. In 2009, he was named by the Nonprofit Times one of the “Most Influential and Effective” fundraisers in the US.

Peter D. Michael

Actor

For over 20 years, Peter D. Michael has been an established actor, voiceover talent and stand-up comedian. He is also an Emmy award winner.

Suzanne Reisman

Journalist

Suzanne is a U.S. international private client lawyer based in London. Suzanne assists philanthropists, their foundations, and international charities with cross-border philanthropy.

Julie Shafer

Journalist

Founder of Julie Shafer Development + Philanthropy, a national philanthropy consulting firm. Ms. Shafer offers a multifaceted skill set honed throughout 20 years as a philanthropy executive bringing a translational approach that bridges the gaps between philanthropists and non-profits.

Jade Shames

Playwright

Jade Shames is an award-winning writer living in Brooklyn, NY. His work can be found in The Best American Poetry blog, The LA Weekly, HOW art and literary journal, and more. He was awarded a creative writing scholarship to attend The New School where he received his MFA.

Amy Singer

Journalist

Amy Singer teaches Ottoman and Turkish history, as well as courses on Islamic philanthropy and the history of charity in the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University. Her recent publications include the book "Charity in Islamic Societies", and in 2008 she was awarded the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Award.

Sharit Tarabay

Artist

Sharit Tarabay painted the portrait of Gerry Lenfest. He is a painter and illustrator living in Montreal. He has his works published in magazines and books around the world.

James V. Toscano

Journalist

Jim Toscano is a principal in the consulting firm, Toscano Advisors, LLC, and an adjunct professor at the School of Business, Hamline University. Recently retired as president of the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, the cardiovascular research and education center of Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, he is a past chair of the Minnesota Charities Review Council and board member of Minnesota Council of Nonprofits.

Susan Yu

Journalist

Susan Yu is a journalist from the San Francisco Bay Area. She is an award-winning news reporter who was formerly based in Hong Kong for 14 years covering stories in Asia for international news media organisations. She is currently based in the United Kingdom where she freelances as a writer, editor and documentary film producer.

The Community Foundation

By Sandra Salmans

How a hundred-year-old idea is reshaping philanthropy around the world.

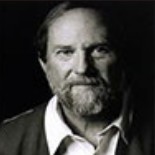

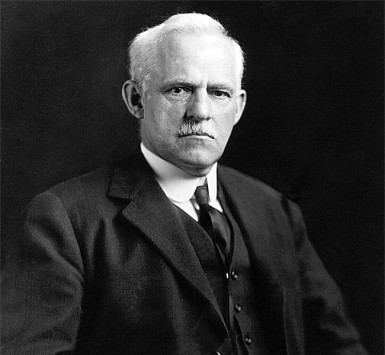

Carnegie and Rockefeller had recently established—and lavishly endowed—their eponymous foundations when Frederick Goff, president of the Cleveland Trust Company, had a different idea: a “community trust” to which the city’s philanthropists could all contribute. Interest on the money, it was declared, would fund “such charitable purposes as will best make for the mental, moral, and physical improvement of the inhabitants of Cleveland.”

Frederick-Goff

Frederick-GoffThus, 100 years ago, was born the world’s first community foundation. (Bequests were, not coincidentally, deposited at the Cleveland Trust Company—setting a precedent for the charitable funds later established by financial services companies such as Fidelity, Schwab and Vanguard.) The Cleveland Foundation was soon leaving its mark on the city, supporting the creation of the so-called “emerald necklace” of the city’s parks, shaking up the corrupt judicial system, spearheading public school reforms that included equal education opportunities for girls. And within five years, community foundations (CFs) had sprung up in Chicago, Boston, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Buffalo, NY.

The growth of CFs since then has been immense, immeasurably greater than even the visionary Goff could have dreamed. Today there are an estimated 700 CFs in the US. According to CF Insights, a consultancy specializing in community foundations, assets at CFs in the U.S. totaled $66 billion in 2013, an increase of $8 billion over the previous year. The Silicon Valley Community Foundation (SVCF) led the way, at $4.7 billion, followed by the Tulsa Community Foundation, with $3.9 billion, and the New York Community Trust, with $2.4 billion. (SVCF’s assets, which ballooned with a $1 billion gift from Mark Zuckerberg in 2013, surged ahead again in 2014 with a $500 million stake in the camera maker GoPro from its founders.)

Mark Zuckerberg

Mark ZuckerbergIn 2013, commemorating the 100 years since the first CF was established, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation created a chair on community foundations at Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. And this past October, to celebrate the centenary of the CF, the Council on Foundations gathered leading philanthropic organizations in Cleveland, where it all began.

What’s more, the rest of the world—including the developing world—is rapidly following America’s lead. According to the latest tally by WINGS (Worldwide Initiatives for Grantmaker Support), a global network of grantmaker support organizations, and the Community Fund Atlas, which is underwritten by the Cleveland Foundation, there are currently some 1,100 CFs outside the US, in more than 50 countries and on six continents. Having launched in the US and Canada in 1914, the CF crossed the Atlantic to Britain about 35 years ago, took root in Germany around the time of reunification, spread to Russia and the former Soviet states, and is currently establishing a foothold throughout the developing world. Between 2010 and 2014, eight new CFs were established in Asia-Pacific, four in sub-Saharan Africa, four in Latin America and two in the Middle East. As the Mott Foundation aptly declared in its 2012 annual report, CFs are “rooted locally, growing globally.”

Whether in the industrialized world or the emerging one, CFs are identical in one key respect: They are public charities that tap the wealth of their communities, with the goal of redistributing it locally. That mission has universal application, asserts Emmett Carson, who is the SVCF’s chief executive officer and is also the visiting holder of the new Mott chair on community foundations. “We should think of the community foundation concept like water,” he says. “The water is the same, but it takes on the shape of whatever community you pour it into.”

Emmett Carson

Emmett CarsonAnd the fact is that CFs differ markedly from one country to another—and, increasingly, even within a country. In the developed world, many CFs are taking on a more activist role than in the past, initiating projects and partnerships as well as donating to established programs. What’s more, many are traveling far beyond their borders, accepting funds from a wider audience and playing a role on the national and even international stage

Meanwhile, the CFs that are springing up in less developed areas—Africa, Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe—are digging deep into their communities to convince residents to trust the very concept of pooling and distributing funds. While endowments and professional leadership are the hallmarks of long-standing CFs in the US, money necessarily takes a back seat to other priorities among CFs in emerging countries, where there are only small pockets of wealth. “They have to prove they’re relevant to the community and need to establish trust where often there are low levels of trust,” notes Nick Deychakiwsky, program officer for the Mott Foundation’s civil society team. In fact, in many cases those CFs have received a jumpstart by foundations such as Mott, Ford, Open Society and Aga Khan, and also appeal to the diaspora for funds.

Nick Deychakiwsky

Nick DeychakiwskyAs Jenny Hodgson, director of the South Africa-based Global Fund for Community Foundations, observes, community philanthropy is as old as, well, communities themselves. “Every country and culture has its traditions of giving and mutual support between family, friends and neighbors,” she has written, pointing to the tradition of burial societies across Africa and hometown associations in Mexico.

However, the new generation of community philanthropy institutions—fueled by factors ranging from a growing concentration of wealth to the popularity of social media, according to WINGS executive director Helena Monteiro—take a more strategic approach to giving. “Most are about development rather than donor services, and they do a lot of capacity building,” Hodgson told Giving. “They’re building civil society, essentially.” As the Kenya Community Development Foundation, a CF established in 1997, asserts on its website, its goal is “the growth and sustainability of communities by their strong engagement in owning and driving their development efforts.” (Italics are KCDF’s.)

Helena Monteiro

Helena MonteiroA sampling of this new breed of CFs offers a glimpse of the variety of programs being undertaken:

- In Egypt, the Community Foundation for South Sinai is working to support the Bedouin, who have long been marginalized. The CF is working on several fronts to raise the tribes out of poverty and preserve their heritage; projects have included teaching the women how to make useful wool products, and providing a camel to a boy who was his family’s breadwinner.

- In Costa Rica, the Monteverde Community Fund, initially founded to invest tourism revenue in preserving the rain forests, has added a social portfolio. Among other projects, it is promoting a community Internet-based radio station, training local youth to create programming and encouraging them to engage in public discourse.

- In Romania, multiple CFs have organized annual “swimathons” to raise their profiles, garner funds and spread the ethos of sharing. In Cluj, the country’s second most populous city, revenue went to support new programs for young people, including a robotics class in an elementary school and education for students with special needs.

- On the West Bank, the Dalia Association, a Palestinian CF, gave women from nearby villages $6,000 to build a park. The women went on to secure additional donations, including the land, utility hookups, a basketball court, a playground and a library.

- In Slovakia, the Banska Bystrica City Foundation—Eastern Europe’s oldest CF, initially launched as a World Health Organization project—has assembled a group of local donors that assist the city’s street children, provide support for the local Roma community, and encourage younger people to take an interest in philanthropy.

While all these CFs have struggled to raise money, elsewhere they have also encountered tight governmental controls or opposition. Even there, however, they are making headway. According to a recent report by CAF (Charities Aid Foundation) Russia, a support group for charitable and nonprofit groups, nearly two-thirds of the membership of CF governing boards comes from the authorities and business; even so, starting with one CF in 1998, Russia today has more than 45 community foundations. The situation is more problematic in China, where very few private organizations are permitted to do fundraising, grantmaking is relatively unknown and civil society is weak. Still, says Hodgson, “everybody is talking about community foundations in China. There’s lots of energy right now.”

That’s also an apt description of the situation in the US, where the biggest CFs are stepping up their game. Rather than limiting themselves to making grants to established programs, “community foundations are increasingly moving into the sphere of brokers for community solutions,” declares Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker, who heads the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo in New York State. Dedecker’s group was the prime mover in launching Say Yes to Education, an initiative that has brought together school parents, union leaders, the business sector and other stakeholders to provide year-round support to students K-12, including college scholarships.

Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker

Clotilde Perez-Bode DedeckerArguably the most striking example of the supercharged CF is the Silicon Valley Community Foundation. The result of a merger of two leading CFs in 2006, SVCF is not only the largest single grantmaker to Bay Area nonprofits, it’s the fifteenth largest international grantmaker in the United States, according to Carson. Furthermore, while SVCF draws much of its wealth from the affluent high-tech community, it also has donors who neither live in the Bay Area nor give to it, but choose to use SVCF as the means to distribute their philanthropy.

To Carson and others, these developments represent a natural progression for CFs in a society that is ever more global. “People increasingly see themselves as national citizens and, more likely, as global citizens,” he notes.” And because many Americans, or at least their parents, hail from different countries, they want to be able to send money overseas as well as to contribute to their new homelands. To compete in this arena—and also to counter the inroads made by financial services companies such as Vanguard and Fidelity, which are vying for donor-advised funds—the leading community foundations are carving out a niche in international philanthropy.

To some people in the CF world, venturing so far afield seems incompatible with the very notion of a community foundation. “A part of me says, ‘Shouldn’t it all be local?’” says the Mott’s Nick Deychakiwsky. But as someone with his own strong spiritual ties to Ukraine, Deychakiwsky concedes that “we’re all living in a more globalized world.” Ultimately, he hopes, globalization will lead to US-based CFs becoming more involved with community foundations abroad—relationships that could benefit organizations in both the developed and developing world. (And there are surprising similarities: Experts notes that CFs in emerging countries have a lot in common with those in rural areas of the US such as the deep South, where “hyperlocal” community development remains the sole focus.) “It’s amazing how much is transferable,” agrees Dedecker of the Community Foundation of Greater Buffalo, who is exploring the sharing of best practices with a CF in Nottingham, England. “The universal drive is for significant change and a strong sense of place,” she concludes. “That’s what unites us all.”

Eileen Heisman

By Doug White

The CEO of the National Philanthropic Trust is going global with the brand and donor-advised funds.

“Charitable giving has a new look,” Time magazine recently reported, “one that is broadening the giving pool and helping keep the dollars rolling into nonprofits even during tough economic times.”

That new look is a method for giving called “donor-advised funds,” or DAFs. This is how it works: A donor opens an account at a “sponsoring organization,” such as a community trust or the charitable arm of a financial services company. While any contributions to the account are immediately tax-deductible, the donor generally has no deadline for disbursing the funds. It’s today’s go-to for philanthropists who aren’t ready to commit their wealth to specific organizations or don’t want the burden or expense of establishing their own foundation. DAFs, reports Giving USA, which tracks the annual growth of philanthropy, “are the fastest growing charitable vehicle in the country.” They have become so popular that they now represent more than $37 billion under management in the United States alone.

Technically, the DAF dates back to 1931, when The New York Community Trust invented the arrangement. However, not much happened for the next 60 years. “People didn’t realize the donor-advised fund model would work,” says Eileen Heisman, president and chief executive officer of National Philanthropic Trust (NPT). But in the early 1990s the Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund received a favorable ruling from a federal appeals court that said DAFs have charitable status, even when they’re under the aegis of an investment firm. Other groups quickly joined in.

Located in the Philadelphia suburb of Jenkintown, NPT, founded by the Pitcairn family in 1996, is today a DAF heavyweight. With more than $1.7 billion in charitable assets under management, NPT ranks among the 25 largest grant-making bodies in the U.S.

Heisman says that DAFs give donors the benefit of professional guidance. “Whether a donor wants to turn an illiquid asset into a gift or create a global grant or a multi-year grant, we hold a mirror up to what the donor wants and reflect best practices in the philanthropic world,” she says. That can include advice on how to structure the gift and outline its goals, as well as ongoing stewardship as donors regularly make their charitable decisions into the future.

But when it comes to how they want their money spent, donors “know what they want to do,” says Heisman. “Donors to DAFs are pretty well informed. They come in with a lot of energy about giving to their causes. They’re engaged philanthropically, many serve on charitable boards, and they’re using us as a way to fulfill their monetary philanthropic goals.”

Still, groups such as NPT do more than distribute alms. “Some people think a DAF is merely a wink for total [donor] control, but it’s really not,” Heisman notes. “Every document clearly states that NPT has the final say over how the money is to be spent. And we reinforce that verbally. We will honor requests that are legitimate, but if you want to go outside things that are legal then we won’t do it.” For example, a gift to an individual from a DAF is forbidden.

Although NPT’s donors are savvy, they still need to be reminded that their wishes might not stand the test of time. Heisman recommends that they include an escape clause in their gift agreements, permitting NPT, usually after a donor’s death, to spend the money on a similar cause if the original intent is no longer possible. “We have the obligation—and undertake the risk—to distribute the money properly,” Heisman says, “and we’ve seen so much that we almost always know more than donors when it comes to structuring the gift agreement. We also tell them that something might be legal now but the laws could change five years from now. Some donors embrace an escape clause in an instant. Others go kicking and screaming. If they never want to change any of their donative intent and if the purpose becomes obsolete, it’s going to be our job to figure something out.”

Congress and the IRS have long struggled with the concept of the donor-advised fund, and in the Pension Protection Act of 2006 Congress did clarify for the first time many definitions and regulations relating to DAFs. Still, the absence of a spending rule worries some legislators. Although foundations are required to spend at least five percent of their assets on their programmatic activities, public charities are not. So, the concern goes, DAFs are nothing more than parking lots where donors can stash money indefinitely and take healthy charitable deductions without actually helping society. The reason the charitable income tax deduction exists is to encourage people to give; the idea is that the foregone tax revenue will help society in ways that government cannot. So legislators might very well think there should be some minimum requirement to ensure that at least some of the deducted donations are actually injected into society’s bloodstream.

But that concern is misplaced, according to Heisman. “Donor-advised funds are actually paying out between 17 and 24 percent, and that doesn’t include overhead, as is the case with foundations,” she says. The National Philanthropic Trust conducts a lot of research on the model throughout the country, perhaps the most of any organization. “The issue about us being these warehouses is not warranted,” she adds. “Money is pouring out the door. We encourage philanthropy.” She sees no need for a required minimum annual payout. In fact, it could be counter-productive. “If you impose a five percent minimum, it may very well become a maximum in people’s minds. It actually could hamper giving. Why would you take a group of entities that are paying 20 percent and say you have to give out five percent per account when the aggregate is humongous?”

Heisman sees her biggest challenge, and perhaps NPT’s biggest opportunity, as one of shaping the future. While there’s no way private philanthropy can ever replace the government’s role in helping society, it can seed some interesting projects. She mentions NIH, the National Institutes for Health, which is a government agency. “NIH won’t fund anything without preliminary findings from smaller experiments, and private philanthropy often funds those smaller experiments. And not just in medicine. Private philanthropy can provide seed money for new ideas to emerge in many areas. “

A favorite teacher of Heisman’s once talked to her about “ideas coming from the fringe of society, and that when they mature they become mainstream.” Philanthropic money can be used to attack the root cause of a problem, not just the symptom. “You want to be funding the stuff on the fringe,” she says. “Some of it will become mainstream.” The women’s rights movement is another example. “There was a time,” Heisman says, “when women’s shelters were considered fringe organizations. Rape assistance? That was really radical. Now, nobody thinks they’re radical, but at the time it was difficult. Things shift and then people don’t even remember.”

When she talks with donors, she says she always tells them “not to be afraid of taking a risk. Some of the most creative thinking in the social sector is by people who are in emerging organizations. If the idea doesn’t mature, it doesn’t mean you were a failure. Maybe that idea could be the next big change in the social sector.”

At NPT, the next big change is expansion overseas and the organization is soon going to be offering the same services to donors outside the U.S. that it does domestically. To be sure, Great Britain’s philanthropic landscape is different from America’s. The federal government in the US as well as many state governments has passed legislation to actively promote charitable donations to a degree that few other nations have. It’s still unknown whether the British will take to the American approach, but it’s worth finding out. As Heisman counsels her donors, “Always take risks.”

What Women Want

By Kecia Barkawi

When I started VALUEworks, a Zurich-based multi-family office, over ten years ago, two concepts were still rather nascent in the wealth management industry: philanthropic advisory as a service and women as a market. Back then, it was not the norm to put philanthropy at the forefront of wealth and family estate planning as it was a consideration usually reserved for retirement, old age, or even death. At that time, women were also not viewed as the most desired clients and more frequently were considered wives or daughters who married into or inherited wealth with little financial knowledge, let alone decision-making power, of their own.

Much has changed since then. Philanthropy has now become a valuable component of family governance and multi-generational planning for wealthy families. Moreover, the tide for women has shifted. In the US, it is believed women will own two-thirds of wealth in the next decade, driven by generational and spousal transfers. In Asia, a new generation of women is transforming the region’s cultural legacy as more affluent, educated, and empowered women come into the picture.

Women are wielding more financial power and astuteness. The movement is real, global, and here to stay. However, the financial industry does not seem ready to serve the needs of wealthy women, even though these are more likely than men to work with advisors whom they value highly. A study on Women of Wealth by Heather R. Ettinger and Eileen M. O’Connor published in 2011 showed that women know what they want. They want to be understood and listened to—the whole story, not just the financials. They want a tailor-made approach focused on their unique needs—not a generalization about women issues, or a product. They want honesty and transparency, and a clarity of their undertakings and what the risks involved are. And philanthropy advisors, too, must fully grasp what this means.

Kecia Barkawi

Kecia BarkawiMuch has been written about gender differences in giving. Sondra Shaw-Hardy and Martha Taylor have expertly illustrated these in their 2010 book, Women and Philanthropy. In my twenty years as wealth advisor, I have come to believe that gender differences are important to keep in mind. Yet, still today, many women of wealth continue to face challenges getting customized services. They struggle to find a truly understanding advisor, because they are either patronized or treated differently on account of their gender. In competing to offer services for women, many in the industry have opted for a cosmetic shortcut. As someone once wrote, “Changing the font to pink doesn’t change the service.”

Together with my mainly female team I pursue a sincere and holistic approach that allows our valued female clients to become engaged and motivated leaders in their philanthropy, not wallflowers.

While writing this article I have reflected on what I have learned from years of philanthropy advisory, but also as founder and CEO of a multi-family office. Below is a list of five key observations which could be useful and equally applicable to any of an advisor's clients.

- Understand their journey. Women play multiple roles. They own successful businesses, but are also mothers who care for kids and manage a household. They are wives who support their spouses, and daughters who care for older parents. Where they are on their professional and personal journey matters tremendously to their philanthropic decisions. As Heather Ettinger and Eileen O’Connor highlight in their study, transition issues such as death, divorce, retirement or being caught in the so-called “sandwich generation” of caring for children and aging parents, define the needs, expectations and financial concerns of successful women. Advisors have to approach these phases in the client’s life with deep sensitivity as these roles matter a great deal. Equally important is taking in the big picture on how these roles change over time. A good advisor should think ahead of these transitions.

- Encourage leadership. While we celebrate how many women have taken the reins of the most influential philanthropies today, there are countless others who remain in the background. Being a leader isn’t easy as it means accountability for financial, operational and strategic decisions. It also implies understanding more fully the intricacies of running a foundation, or spearheading fundraising, or being the face of an advocacy. As advisor I can provide a great service by identifying the personal development needs of my female client, identifying skills or experiences that will help her fulfill her role and be proud of her philanthropic achievements.

- Address issues of risk. Women are characterized as more risk-averse and conservative when it comes to finances than men. The 2011 Study of High Net Worth Women’s Philanthropy by the Center on Philanthropy reports that nearly 40% of women are not willing to take any risks with their philanthropic investments versus just 22.8% of men. I generally believe in a conservative approach. We women are less prone to overconfidence and tend to plan more carefully for uncertainty. As an advisor faced with a highly risk-averse client, I find providing an educational path the most effective approach to ensuring she feels comfortable with her decisions. It is important to acknowledge and highlight risks and to admit that we cannot possibly know everything and investigate every scenario. Nevertheless, by bringing in experts, organizing open discussions, exchanging useful readings and creating an atmosphere of discovery, we can all learn together. The most meaningful philanthropic engagements come out of such dialogues and exploration.

- Connect them to other philanthropists. There are many successful women of wealth who are seeking to make a real difference with their philanthropy. Often they come across the same challenges and obstacles. One of the initiatives I am very proud of is a Swiss-wide network for women in philanthropy which VALUEworks initiated in 2012. By creating a highly exclusive space for women philanthropists to come together to exchange ideas and learn from each other, we can give them the keys to empowering and enriching their own giving journeys. As advisor I am really motivated by the outcome: clients and contacts are inspired, energized and truly appreciate the connections they make through the network. They become more open to sharing their views and talk about problems encountered and to partnering with others, raising their effectiveness and efficiency as givers.

- It isn’t all about gender. According to the study of Ettinger and O’Connor a big amount of dissatisfaction of women clients stems their perception that gender is the reason for poor financial advice, disrespect and condescension from the financial services industry. We need to reframe our entire approach so that it is not gender-centric which has the tendency to patronize women, alienating them even further from advisors. Successful, empowered, educated women need and deserve competent philanthropy advice, served to them with care and professionalism. Service providers are better advised to invest their time and resources in creating a tailored approach that makes their philanthropy both socially relevant and personally meaningful. And this way, we as advisors can have a greater impact, too.

If we care about excellent service to our clients - male and female - we need to keep our gender biases in check. What women truly want is to be understood and treated as equally special as every other valued client.

Guidestar

By Luke Norman

With data dominating, Guidestar.org has become as familiar as Google to many American donors. Has the website filled a void for consumer education in philanthropy?

Data has been the buzzword in philanthropy for the last 18 months. Just as it has proved to be a major driver for the commercial economy, so it has become the lifeblood of the social economy. Not only are the provision and use of data now key to persuading donors where to place their money, but they are also vital in helping improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the charities and social enterprises funded by such gifts.

Guidestar.org is the shining beacon, or perhaps more accurately the behemoth at the vanguard of this spread sheet revolution. It is a portal, gathering information on nonprofits, packaging it and disseminating it to a hungry public. These numbers and facts are freely available but habitually buried in all manners of gunk, making them harder for the time-pressed donor to access than for a hungry traveller to find a sugar-free snack in a service station.

The idea behind Guidestar, similar to many that have ridden the internet wave, is based on dispensing important information to the masses for free. However, as demand has ballooned, so has it changed shape.

It is interesting to note that when commentators describe Guidestar’s function, many of them fall back on the terms “charity watchdog” or “evaluator”—The Washington Times and Time magazine provide two examples in the last 12 months. However, this is simply not true. Ernest Hemingway once wrote, “Never mistake motion for action.” He might have added, “And never mistake information for endorsement.”

This misnomer is a serious enough issue for Guidestar to have a “Clarification” announcement on its website, stating definitively that its users should not mistake information for endorsement. Indeed, Guidestar’s mission is clear enough: “To revolutionize philanthropy by providing information that advances transparency, enables users to make better decisions and encourages charitable giving.”

Clear enough then. But at some point services like Guidestar reach a tipping point. The level of information along with the number of people accessing and/or relying on that information combine to confer endorsement. And this is a problem. Guidestar’s own, hard-earned reputation should not be transferred seamlessly to the organisations represented on its sites, but it is. This presents a dilemma; if Guidestar and its ilk are presenting such information. should they be evaluating it as a matter of course?

While charitable giving in the U.S. accounts for less of the country’s gross national income than in other nations, it far outpaces any other country in pure financial terms. Particularly in a context of such heavy lifting, givers feed on information. Indeed a scan of the newspapers during Christmas every year, a key season for donations, often reveals almost unanimous advice: “know your charities.”

Donors are taking this onboard. More than 90%, according to a Guidestar report, said in 2013 that nonprofit performance was an important factor in their giving and one that they wanted to be able to analyze more easily. Conversely, the same donors admitted that just 30% of them actually research the charities their cash reaches.

Guidestar is caught in a conundrum. The majority of charitable donations in the USA are made by individuals, specifically, 73% of the $298 billion that was given in 2011. Concurrently, the vast majority of Guidestar’s users—98% of them—access just the free-to-air raw data that they provide. Guidestar and its competitors have all started to deliver premium services in which they rate, analyze and pass judgment on the performance of the charities they list. For instance in 2012, Guidestar teamed up with the Non-Profit Finance Fund comparing the financial health of nonprofits. It is a practice that has spread. In 2013, 15 of the biggest US foundations launched a “Reporting Commitment” making grants data available. Simultaneously, the China Foundation rated 2,000 of its foundations with an elaborate transparency index.

In these confusing waters, two things are clear: the first is that data use and access are set to be institutional for the entire social economy (with that comes ownership, another thorny question); the second is that raw data services, such as those that Guidestar provides, will inevitably become available at source. Guidestar’s core offering, the 990 forms that tax-exempt nonprofits are obliged to file with the Inland Revenue Services (IRS), has a shelf life. Currently, the IRS is ill-prepared to provide the information that organizations—and the clients they represent—are asking for. The provision of raw data via hard copy or DVD will soon have to give way to more easily accessible digital archives as demand for information continues rising.

So Guidestar is faced with a raft of key questions about its next steps: how can it maintain its core operation but continue experimenting? How can it analyze data without morphing into a full-out advisory service? How will it make open data an asset and not a liability?

Despite the "clarification" on its website, Guidestar already offers extensive analysis. In the recent past it has teamed up with several partners to provide evaluations. Philanthropedia, an internal division of the organization, rates nonprofits according to the work they do, with 2,500 experts reviewing 3,500 outfits in 2012, while Takeaction@ Guidestar measures impact to help identify the most effective nonprofits in particular cause areas. On top of this, a TripAdvisor-style offering, GreatNonprofits, provides personal reviews to produce average user ratings that accompany some nonprofit listings on Guidestar.

These are of course all premium services with corresponding costs. Still, just 2% of Guidestar’s users are paying for them. So surely the key question becomes, is there a paying market for this valuable data? Or, will it too inevitably become free-to-air?

It is a devilish Rubik’s Cube of a problem. Almost all of Guidestar’s users want free, raw data as a compass for their giving, but 90% of those surveyed want their data evaluated and analyzed. Still, just 30% of donors actually bother to research the causes they give to and Guidestar’s paying customers represent a tiny fraction of the pot. Headache? Imagine Guidestar’s and this is before one considers the thorny problem of storing, protecting, and dictating ownership of such data.

Given Guidestar’s history of excellence, it seems likely they will find a way. As our perfect case study, let’s hope they do, and quickly.

Matchmaker

By Ron Finlay

Facilitating professional volunteering is growing in popularity in the UK as an answer to 21st century life pressures.

Big change is happening in Britain’s volunteering. As baby boomers move into their sixties, the traditional notion of charity volunteers being ladies helping out with admin tasks or assisting in charity shops is fast giving way to the rise of the professional volunteer – as often male as female.

These pro bono workers, with years of experience behind them, naturally want to put their skills to good use. But how do they find the right match, and fit new voluntary commitments into lives that remain full of other 21st century pressures?

You might imagine that demand for their services would be overwhelming. With 165,000 registered charities in the UK, and an economic climate that, despite the recent upturn, remains really challenging for the third sector, there is certainly plenty of need for skilled business people. But those who need it most – small to medium-sized charities and community groups that are struggling to generate income and plan strategically – are usually the least able to articulate their requirements. They often just don’t have the time or the mindset to ‘go to market’.

This is where ‘brokers’ really come into their own.

These modern-day matchmakers not only identify the frontline welfare organisations that need support, but also help them specify the services they require in such a way that fit with what professional volunteers can offer.

As with any good betrothal, after the match has been made, the broker’s role is to support the couple in the early stages of their relationship. Really important to secure the buy-in of the professional volunteer is to design their input so that they can donate small ‘bursts’ of high impact time on a regular basis for a fixed term.

“Running a strategy workshop for a charity board is really rewarding,” says Sue Davidson, who has been bringing her C-suite experience from international organisations to small charities for over two years. “The last thing I want is an open-ended low value commitment, but if I can help trustees secure a better future for their charity, it’s a win-win for them and me.”

The matchmaker will also help out by drawing on further resources if a charity requires more time and skills than a single volunteer can provide, freeing each side from a possible guilt-trip.

The success of the model is clear. While overall volunteering in Britain has remained fairly static over the last few years – with 29% of the population volunteering regularly – at The Cranfield Trust, we’ve seen our volunteer register grow 15% year-on-year.

Amanda Tincknell, Cranfield Trust

Amanda Tincknell, Cranfield Trust

It’s a different kind of philanthropy. Frontline charities benefit from an injection of high value skills, and the contributing business people build their networks and knowledge while deriving satisfaction from the volunteering experience. As Sue says ‘I like working with clever, motivated, driven people. I would really encourage those in the private sector with years of transferable experience to give their time.’ The Royal Voluntary Service estimates that British volunteering by people aged 50 and over will grow in value from £10bn to £15bn by 2020. Much of this will be by those offering professional skills. Long live the matchmaker!