About

Global Team

Roberta d’Eustachio

Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Roberta d'Eustachio (Rd'E) is an entrepreneur obsessed with delivering media from the social investor/philanthropist's point of view. That desire led to founding The American Benefactor, the first consumer magazine for philanthropists, as well as Giving Magazine and each of its subsequent evolutions: from print, to digital, to mobile with Facebook Instant Articles, delivering stories of social impact - for everyone, everywhere.

Rd'E has consulted with, and/or received investment from, leading global brands, including: The Economist, the Financial Times, Euro Money/Institutional Investor, the Pitcairn Family Office, Fidelity Capital and the World Bank as well as philanthropists and social enterprises around the world.

After serving as chief-of-staff to Dame Stephanie Shirley, the British Government’s Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy, Rd'E founded the AmbassadorsForPhilanthropy.com enterprise to give social investors a voice worldwide.

Dame Stephanie Shirley

Philanthropist & Believer-in-chief

Dame Stephanie “Steve” Shirley is a British entrepreneur turned philanthropist. She originally arrived in London as an unaccompanied Kindertransport child refugee from Austria during WWII. “Steve” was an early pioneer in technology and, after taking her company public, she has given more than $100 million to organizations that specialize in autism research and technology, including founding the Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University. Appointed by Prime Minister Gordon Brown to the title of the British Government's Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy 2009-2010, she believes in the advancement of the philanthropist voice worldwide.

Her memoir “Let It Go” was recently published, chronicling her life so far.

"Steve" is the Believer-in-chief to Giving Magazine, providing the means to imagine and execute its potential to the fullest.

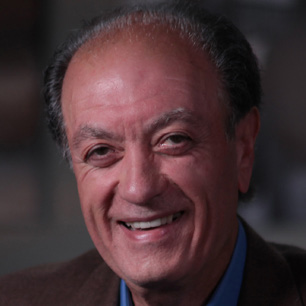

Jerry Alten

Chief Curator

Jerry Alten is a world-renowned art director of magazines, across all devices, and other marketing and advertising work, winning many prizes in the media field. Under Walter Annenberg’s ownership of TV Guide, Jerry took the circulation from 5 million up to 19 million during his tenure as art director. He continued to work with Rupert Murdoch’s organization after the buy out of TV Guide and created the first interactive website for the magazine. Jerry was also the original investor in The American Benefactor Magazine and art director, which succeeded in obtaining more than $7 million worth of investment from Fidelity Investment's venture firm.

Brian Lipscomb

Chief Technologist

Brian Lipscomb has been involved with technology for over twenty years, and founded technology services company Divergex, based in Philadelphia. Specializing in all aspects of computers, Brian brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to Giving Magazine. His philosophy is: “Do it right, or don’t do it at all.”

Lipscomb adds: “Technology is a constantly evolving industry. People who use technology daily don’t have the time to study and learn all of the new and different terms and capabilities. I work to show people how technology can improve their efficiency, productivity and, ultimately, their lives.”

Jay Balfour

Managing Editor

Before Jay became the Managing Editor for Giving, he was a freelance writer and editor based in Philadelphia. With an academic background in Philosophy he leverages an informed perspective on everything from African music to youth movements in the West for several publications both online and in print. At Giving Magazine he shares a passion for unabated reporting and the ushering in of a new age in philanthropy.

Sandra Salmans

Executive Editor

Sandra Salmans is a New york-based writer and editor who works primarily in the nonprofit field. She began her career as a business and financial journalist at Newsweek and The New York Times, but has also covered national news, education and the arts. Prior to going freelance, she was a senior officer in communications for a leading foundation in Philadelphia.

Nicole Raeder

Digital Design Manager

Nicole delights in great design. That's why her commitment is compulsive; contagious even, to get it right. Or, change it. Or, change it again. Whatever is required to finding the way to the end point, which is sometimes the beginning. In other words, she never gives up, or stops, till the thing clicks.

She also loves cats.

Damon d'Eustachio

Co-Director, Global Membership

A foodie who navigated his way from the city of brotherly love to Charleston, S.C, Damon is devoted to serving nonprofits worldwide that believe the philanthropist voice must be heard.

Damon graduated from the College of Charleston in Art Administration and performed an internship at London’s prestigious Tate Gallery’s New York City office.

Jessica Lambrakos

Co-Director, Global Membership

Jessica is responsible for the management and development of the Global Awards for nonprofits of Giving Magazine for their nominated philanthropists and supporters.

She also serves as founder and executive director of her own nonprofit, “The Naked Truth AIDS Project”, which raises funds for AIDS prevention education programs in the USA as well as Africa.

Nick Cater

Contributing Editor

Nick Cater is a UK-based international writer and editor. A former Fleet Street journalist, he has reported from more than 40 countries so far on stories as diverse as war in Africa, environmental risks in Latin America, disasters in Europe, and the Asian sport of elephant polo.

Luke Norman

Senior Editor

Luke Norman is an experienced journalist and corporate social responsibility consultant. Having started at The Daily Telegraph, Luke has worked for a wide range of international media outlets before moving into the heady world of multi-national corporations and their sustainability commitments. Luke has transplanted himself and his family from London to Rio de Janeiro, where the views he now observes are deliriously engaging.

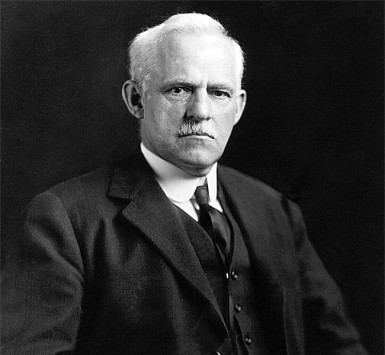

Doug White

Senior Editor

Doug White, a long-time leader in the nation's philanthropic community, is an author, professor, and an advisor to nonprofit organizations and philanthropists. He is the director of Columbia University's Master of Science in Fundraising Management program. He also teaches board governance, ethics and fundraising. His most recent book, “Abusing Donor Intent,” chronicles the historic lawsuit brought against Princeton University by the children of Charles and Marie Robertson, the couple who donated $35 million in 1961 to endow the graduate program at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Kent Allen

Journalist

Kent Allen is a longtime daily journalist and freelance writer. Over the past 20 years, while also writing about philanthropy and nonprofits, he has worked as an editor at The Washington Post, U.S. News & World Report and Congressional Quarterly. At present, Kent is a journalism and history teacher at The Field School, a middle and high school in Washington, D.C.

Lucy Bernholz

Journalist

Lucy Bernholz is a blogger and self-proclaimed “philanthropy wonk”. Her blog, Philanthropy 2173: The future of good, has been named a “best blog” by Fast Company and a “philanthropy game changer” by the Huffington Post.

Kim Breslin

Actor

Kim Breslin is an actress, comedienne, director, producer, artist, and chef. She has been an educator in North Philadelphia for 17 Years. Mother of two incredible children, she lives with her highly supportive cat, The Amazing Sid.

Cheryl Chapman

Journalist

Cheryl Chapman actively promotes philanthropy in the UK and globally via her journalism. She was the editor of Philanthopy UK: Inspiring Giving and now heads City Philanthropy, London, as its Director.

Stephen Dunn

Poet

Stephen Dunn, Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, is the author of 11 collections of poems, including “Different Hours,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 2001.

Regan Good

Poet

Regan Good is a freelance writer and poet living in Brooklyn, New York. She has written for The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times Magazine and others. She is currently at work on a memoir about growing up in a family of writers.

Sharilyn Hale

Journalist

Sharilyn Hale, M.A., CFRE is Founder and Principal of Watermark Philanthropic Advising where she offers strategies for meaningful giving, receiving and leading. A practitioner, author and educator, she brings a global perspective on philanthropy having served the nonprofit sector across North America, Bermuda and the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. She holds a graduate degree in Philanthropy & Development and is past Chair of CFRE International, the global certification for professional fundraisers setting standards for ethical and accountable practices.

Crystal Hayling

Journalist

Believer in a better world. Uppity advocate for social change. Former philanthrapoid. Crystal lives in Singapore where she helps donors develop strategy for effective grantmaking. She serves on numerous boards, and is a speaker and writer on civil society. Twitter: chayling

Holly Howe

Journalist

Holly Howe is a strategic communications consultant with a particular focus on the arts. She works as a freelance journalist, writing for various publications including FAD, RWD, House (published by the Soho House group) and the Irish Examiner. She also runs the Culture Vultures, a networking group for people in media and the arts. She can be found tweeting at @ hollytorious and in her occasional spare moments, she posts on her blog www.postcardsfromholly.blogspot.com

Wangsheng Li

Journalist

Wangsheng Li is president of ZeShan Foundation (Hong Kong) and a Senior Fellow of the Synergos Institute (New York City).

Lisa Macdonald

Journalist

Lisa MacDonald is a freelance writer and editor based in Toronto. A passion for philanthropy drives her involvement in initiatives that bring information and innovative ideas to Canada’s nonprofit sector leaders. Tweet her at @lisalmacdonald.

Andrew MacLarty

Actor

Andrew MacLarty is a New York based actor who has appeared on Boardwalk Empire and White Collar. Non-profit work includes narration for Partnership for a Drug-Free America, performances at the United Nations for Hurricane Katrina relief benefit shows, and Barefoot Theater Company’s ROCKAWAY benefit for Hurricane Sandy victims.

Bruce Makous

Journalist

Bruce Makous, ChFC, CAP, CFRE, has been a professional fundraiser for over twenty-seven years, with leadership positions in major educational, healthcare, and arts organizations. In 2009, he was named by the Nonprofit Times one of the “Most Influential and Effective” fundraisers in the US.

Peter D. Michael

Actor

For over 20 years, Peter D. Michael has been an established actor, voiceover talent and stand-up comedian. He is also an Emmy award winner.

Suzanne Reisman

Journalist

Suzanne is a U.S. international private client lawyer based in London. Suzanne assists philanthropists, their foundations, and international charities with cross-border philanthropy.

Julie Shafer

Journalist

Founder of Julie Shafer Development + Philanthropy, a national philanthropy consulting firm. Ms. Shafer offers a multifaceted skill set honed throughout 20 years as a philanthropy executive bringing a translational approach that bridges the gaps between philanthropists and non-profits.

Jade Shames

Playwright

Jade Shames is an award-winning writer living in Brooklyn, NY. His work can be found in The Best American Poetry blog, The LA Weekly, HOW art and literary journal, and more. He was awarded a creative writing scholarship to attend The New School where he received his MFA.

Amy Singer

Journalist

Amy Singer teaches Ottoman and Turkish history, as well as courses on Islamic philanthropy and the history of charity in the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University. Her recent publications include the book "Charity in Islamic Societies", and in 2008 she was awarded the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Award.

Sharit Tarabay

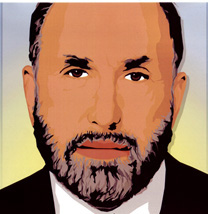

Artist

Sharit Tarabay painted the portrait of Gerry Lenfest. He is a painter and illustrator living in Montreal. He has his works published in magazines and books around the world.

James V. Toscano

Journalist

Jim Toscano is a principal in the consulting firm, Toscano Advisors, LLC, and an adjunct professor at the School of Business, Hamline University. Recently retired as president of the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, the cardiovascular research and education center of Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, he is a past chair of the Minnesota Charities Review Council and board member of Minnesota Council of Nonprofits.

Susan Yu

Journalist

Susan Yu is a journalist from the San Francisco Bay Area. She is an award-winning news reporter who was formerly based in Hong Kong for 14 years covering stories in Asia for international news media organisations. She is currently based in the United Kingdom where she freelances as a writer, editor and documentary film producer.

The Apple Founder's Philanthropic Legacy

By Sandra Salmans

By now, the story is the stuff of legend. How the tall blonde woman known only as Laurene met with a young Latina in East Palo Alto—a neighborhood bypassed by Silicon Valley’s dot-com boom—every few weeks for mentoring. How the girl confided in Laurene about her difficult childhood. How, without Laurene, she might not have become the first person in her family to graduate from college. And how, as a freshman at the University of California, Berkeley, she learned from a news article that Laurene was the wife of Apple’s co-founder, Steve Jobs—“Silicon Valley royalty,” as The New York Times put it.

As Steve Jobs’ wife for 20 years, Laurene Powell Jobs practiced a low-key philanthropy that matched the style, if not the substance, of her famously publicity-averse husband. In 1997, as a consequence of her experience working with high school seniors on the college admission process, she co-founded College Track, a comprehensive after-school advisory program that las year reached more than 1,600 high school and college students in Northern California, New Orleans, and Aurora, Colorado. Powell Jobs’ contributions to College Track, where she still serves as the chair, are made through Emerson Collective, an organization she established about a decade ago, and which—because it is incorporated as a small business rather than a tax-exempt 501(c)(3)—does not have to publicly report its donations. She is also a member of some half-a-dozen nonprofit boards, including that of Stanford University, where she earned an M.B.A. “If you total up in your mind all of the philanthropic investments that Laurene has made that the public knows about, that is probably a fraction of 1 percent of what she actually does, and that’s the most I can say,” Powell Jobs’ longtime friend and fellow philanthropist Laura Arrillaga-Andreessen—herself a member of Silicon Valley royalty, as the wife of Netscape founder Marc Andreessen—told the Times.

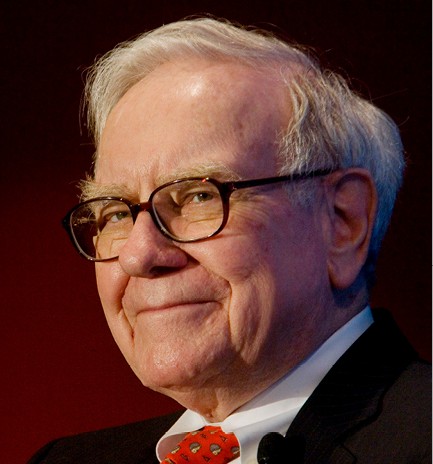

That commitment stands in marked contrast to Steve Jobs’ indifference, if not outright aversion, to philanthropy—an attitude for which he came under harsh criticism during his lifetime. Although some of his greatest fans, including the MacDailyNews blog, have speculated that Jobs gave away millions secretly (one rumor has focused on a very large anonymous donation to a San Francisco cancer center)—there is no paper trail to support such conjectures. On the contrary, Walter Isaacson, Jobs’ biographer, writes that not only was he “not particularly philanthropic,” he was contemptuous of people who “made a display of philanthropy or thinking they could reinvent it.” Although he “admired” Powell Jobs’ work in education reform, Isaacson adds, he never visited her after-school centers. Of course, it’s important to recall that Bill Gates and even Warren Buffet were criticized at one time for being tight-fisted, until they started to give billions away. Had Jobs lived, it’s conceivable that he would ultimately have met the challenge to “think different” in philanthropy as brilliantly as he did in technology.

Jobs’ death in 2011 left Powell Jobs as one of the richest women in the world, with some $12 billion, most of it in Disney stock, in her name. It also gives her greater freedom to lend her voice and spend her money openly on behalf of the causes she supports, and that is precisely what she has begun to do. One of the first issues she has embraced is immigration reform, a natural outgrowth of her focus on education and her personal experience as a mentor.

The Emerson Collective, which didn’t even maintain a website a couple of years ago, currently has an up-to-the-minute site that addresses progress on immigration legislation as well as protecting the environment, education reform, and gun control. Last year she bankrolled a 30-minute film, “The Dream is Now,” about four young people whose prospects are bleak because they are in the U.S. illegally; she took it to Capitol Hill to showcase it to members of Congress, and sat for a rare interview with NBC’s Brian Williams in which she shone as an articulate, earnest advocate, bearing out Isaacson’s assertion that “she is one of the smartest and most grounded people I have ever met.” She is also a deeply private person, like her late husband, and friends say that’s unlikely to change. However, given her commitment “to try to effect the greatest amount of good,” as she told the Times, it’s doubtful that she will be able to pass again as a tall blonde woman known only as Laurene.

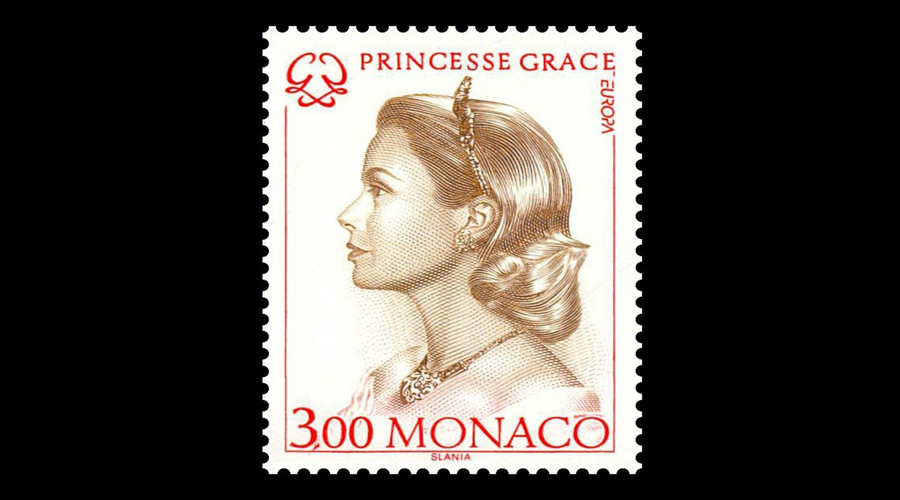

Princess Grace Foundation

By Bruce Makous

Originally created to salve Monaco's royal family's grief, the Princess Grace foundation celebrates three decades assisting emerging talent in theater, dance, and film.

She was the ultimate fairytale heroine, a radiantly beautiful commoner who’d caught the eye of and later married a prince. So when Princess Grace met an early death in a car crash in 1982, at the age of 52, it was fitting that her bereaved husband, Prince Rainier III, would create a foundation in her own country to foster and celebrate the arts.

The Princess Grace Foundation-USA focuses on the Princess’s primary philanthropic interests—discovering and assisting emerging artists in theatre, dance, and film. The foundation, a publicly supported not-for-profit headquartered in New York City, provides contributions to artists who are beginning their careers, primarily in the form of scholarships, fellowships and apprenticeships. To fund the foundation, the Prince mobilized Grace’s supporters, which included the likes of Frank Sinatra and Cary Grant. (The foundation is distinct from the Princess Grace of Monaco Foundation, which the princess created shortly after her marriage to encourage local artists and crafts people.)

Through its flagship program, the Princess Grace Awards, the Princess Grace Foundation-USA provides the financial assistance and moral encouragement needed by emerging artists so that they can focus on the creative process. Applicants must be nominated by nonprofit arts organizations, and a panel composed of distinguished professionals in theatre, dance, and film annually selects the winners on a competitive basis. Since the Foundation’s inception, more than 750 Princess Grace Awards totaling nearly $10 million have been given to performing artists. Many winners have subsequently achieved public recognition and critical acclaim, including Oscars, Tonys, Emmys, and other awards.

Among the notable winners are Robert Battle, the dancer and choreographer who now serves as Artistic Director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater; Yareli Arizmendi, the Mexican actress who played Rosaura in Like Water for Chocolate; Bridget Carpenter, playwright and screenwriter nominated three times for Best Dramatic Series by the Writers Guild of America for her work on Friday Night Lights; and Stephen McDannell Hillenburg, the animator, writer, producer, actor and director best known for creating the SpongeBob SquarePants TV series.

Those Princess Grace Award-winners who subsequently distinguish themselves in theater, dance, or film receive an additional form of recognition—the Princess Grace Statue Award. To date, 54 artists have received this award. A third type of recognition, the Prince Rainier III Award, established in 2005 after the Prince’s death, is presented to eminent artists who have also made significant humanitarian contributions. This award, which includes a grant to the philanthropic organization of the honoree’s choice, has been given to such stars as Julie Andrews, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Twyla Tharp, Denzel and Pauletta Washington, George Lucas, and Glenn Close.

Her family is carrying on her philanthropic legacy. Prince Albert II is the vice chairman of the foundation, and Princess Caroline is president of AMADE Mondiale, the Monaco-based NGO that Grace founded during her lifetime to help children in the developing world. Recently, for example, AMADE has provided support to Syrian children in refugee camps and to families devastated by the typhoon in the Philippines.

In fairytales, the royal couple lives happily ever after. But even when death intervenes, it seems, they can make others’ dreams come true.

Futures

By Lucy Bernholz

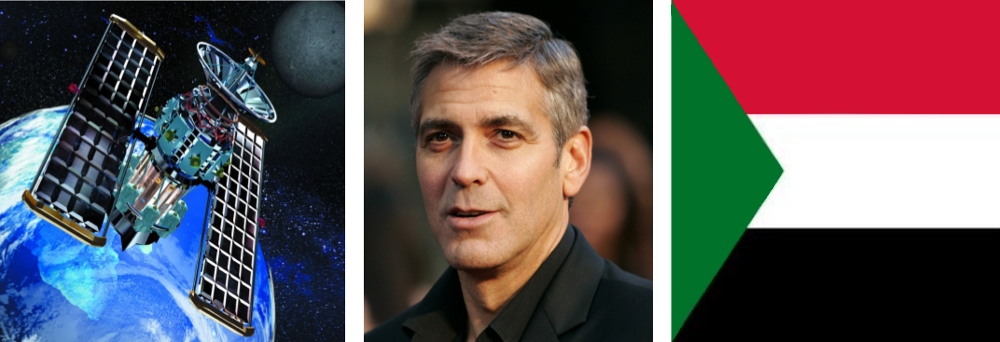

The do's and don'ts of citizen surveillance, Sudan and George Clooney.

Celebrities know a lot about being watched. Maybe that’s one reason for actor George Clooney’s enthusiasm for the satellite camera he’s trained on Sudan.

Sudan has been a longstanding interest for the actor. He’s testified before Congress about the country, and in June 2012 was arrested for protesting outside the Sudanese embassy in Washington, DC, against alleged war criminal President Omar al-Bashir. Since 2010 he’s also funded the Satellite Sentinel Project (SSP), an organization that independently observes the volatile border between Sudan and South Sudan. SSP has become not only a witness to genocide, it is opening up a new frontier in civilian humanitarian aid.

Working through partnerships with the Enough! Project, DigitalGlobe, Google and the Harvard Humanitarian Institute, SSP pairs satellite imagery with on-the-ground mapmakers and analysts. The project tracks military movements, records human rights violations, and builds an evidence base of satellite images paired with reports and data from the field. Even in an age of widespread government surveillance, SSP represents a number of ‘firsts.’ It is a groundbreaking application of military technology within civilian peacekeeping; it is a unique partnership between tech companies, scholars and aid workers; and it brings new data to bear on international policy.

For a full year beginning in 2011, the SSP recorded more than 25 violations of existing peace agreements and military movements that threatened Sudanese villages and people. The broad peripheral vision of the satellites also ensured that the movements on both sides—government as well as rebel forces—were captured. Satellite images of mass graves and smoldering villages provided incontrovertible evidence of events previously hinted at by those on the ground. They not only revealed the extent of the damage, but could be knit together to show the direction and pace of destruction in the wake of moving troops.

It wasn’t long before project leaders recognized that the combination of satellite imagery and ground level analysis could be used to predict future disasters. In September 2011, for example, SSP analysts realized that their satellite images of troop movements pointed to a surefire attack on the village of Kurmulk. They took the unusual step, as a watchdog organization, of issuing a warning, and thousands of people were able to flee ahead of the onslaught.

Not surprisingly, the international response to SSP’s images lags significantly behind the technology. For the humanitarian aid community, however, SSP has signaled a sea change. Humanitarian groups are mostly trained to respond to crises, not to avert them. Nonintervention has been a stalwart feature of humanitarian aid for centuries, and a key reason these groups are given access to war zones in the first place. Changing their rules of engagement may mean saving lives in the near term, but could also result in being banned from conflict zones the next time around. Actively shaping the direction of a conflict means new responsibilities and the need for an updated code of ethics.

The SSP is teaching us that new technology can be applied to humanitarian aid faster than we can predict the consequences of doing so. This is often true of cutting-edge technologies. But rarely is it a matter of life or death.

Elizabeth Wallace Ellers

By Bruce Makous

Introducing social innovators directly to philanthropists, Liz Ellers is making global impact philanthropy more accessible to women in her area.

In a way, Elizabeth Wallace Ellers has been rehearsing all her life for the role she’s playing these days in impact philanthropy. After studying international relations at UCLA, Liz spent time in Mexico and Brazil, and then earned an MBA at Columbia University. She worked as an investment banker for years and then embarked, informally at first, on the path to founding her own donor-advised fund in Philadelphia.

Ellers jumpstarted The globalislocal Fund with a few more than a dozen other local women in 2005 with the intention of addressing the root causes of poverty throughout the developing world. In the ten years since, globalislocal’s membership has grown to more than 50 and the group has dispensed more than $2 million in either outright donations or loans as a part of its growing project portfolio, which includes funding for organizations like Root Capital, a nonprofit investment fund that helps finance small agricultural businesses in Latin America and Africa.

globalislocal's current portfolio

globalislocal's current portfolio

Ellers traces the founding of globalislocal back to her decision to leave Wall Street following the birth of her son; in the early ‘90s, she became involved with collaborative funding and philanthropy out of her own passion for economic development. Even as a well-connected donor, Ellers encountered roadblocks as she developed her own philanthropic portfolio.

“I was just doing this for myself,” she says. “And then I just got a little annoyed. Back then there were a couple conferences that were really the only places you could go to convene with like-minded funders and smart NGO leaders, and, as we evolved, social entrepreneurs. But they were invitation only.”

She more fondly recalls local networks of female philanthropists in her area as a spark and her time at The Philanthropy Workshop, a Rockefeller Foundation education program on strategic giving, as a final step in realizing globalislocal.

“As I learned more and more about the issues—and the impact that is possible—I knew that I had to create a way to share it with others,” she says. “I never, ever intended to do this,” she adds with a laugh. “It got to a point where I had to do it.”

The same Wall Street discipline that shaped Ellers’ thinking for years now pervades the globalislocal structure. The philanthropists are “investors” and “partners” and before an organization is added to the funded “portfolio” a projected social return on the investment must meet minimum requirements. It’s a model built on careful calculation of impact as much as it is on more subjective or emotional social or environmental measures. Metrics include household income, viable crop yields, volume of accessible water, access to health care professionals, and business productivity.

Annual investments from participating partners generally range from $3,000 to $15,000 and Ellers encourages members to meet face-to-face with social entrepreneurs on the ground in Africa, Asia, and Latin America to learn about the issues intimately themselves. Each year, partners receive impact reports that inform their next round of investments. “You’re not just leveraging your money,” Ellers says of the collaborative approach. “You’re leveraging all of your resources. Different people and different foundations have different kinds of resources. It’s knowledge, it’s network, it’s access. People don’t talk about access a lot. Access is sometimes way harder than money.”

Ellers also mentions globalislocal’s ahead-of-the-curve grantee curation as a source of pride: “Our investees are really great,” she says. “We’ve invested in some of these social entrepreneurs before some of the biggest funders in the space have found them.” Besides Root Capital, examples of recently selected social enterprises include the One Acre Fund, which channels loans to farmers in Kenya and Rwanda as they try to increase annual yields, and Partners in Health, which provides patient-centered health care in settings where resources are scarce.

Ellers says that she didn’t set out to make globalislocal itself an all-women group, but she’s embraced the natural development. “Women enjoy collaborating with their peers,” she said a few years ago upon receiving a leadership award from Women’s eNews. “And the majority of the most vulnerable people in the world are women and children. When targeting the causes and consequences of poverty, by definition, we’re targeting women and children. So there’s this great sense of connectedness.”

Still, as gratifying as the results can be, Ellers admits that the type of philanthropy globalislocal pursues is a hard-fought long game. “We focus on solutions to poverty in the developing world,” she says. “Already you’re talking about really challenging, multifaceted, interlocking puzzle pieces. Even when you’re addressing the root causes and providing the access to opportunity for the community to make choices about how to climb up the ladder, these are long term propositions. You don’t go from living on a dollar-a-day to middle-class in five years.”

As for the fund's next steps, Ellers says, "Ultimately, globalislocal's goal is to increase dramatically the number of investors and volume of investments actively engaging these issues. To this end, globalislocal is actively exploring strategic alliances and partnerships in the United Sates and abroad."

Mark Zuckerberg/Priscilla Chan’s $45 Billion Dollar Charitable LLC

By Doug White

Making Philanthropic History

In December 2015, Priscilla Chan and her husband Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s co-founder and chief executive officer, made history — not because of their enormous wealth but because they pledged to use almost all of it to make the world a better place.

The couple pledged to give away 99 percent of Facebook’s stock, which, at the time of the announcement, was valued at approximately $45 billion, making it the largest pledge in the history of philanthropy.

When they made their stunning announcement, they were speaking primarily not to the media but to their newborn daughter Maxima.

In a letter that will undoubtedly rank among the most important that will ever be addressed to Maxima, her parents outlined their profound goals to improve health and education, and to decrease inequality. "Our society has an obligation,” Chan and Zuckerberg wrote, “to invest now to improve the lives of all those coming into this world, not just those already here. But right now, we don't always collectively direct our resources at the biggest opportunities and problems your generation will face."

They then acknowledged one of the more ignored basic truths of philanthropy: fundamental change requires time: “We must make long-term investments over 25, 50 or even 100 years. The greatest challenges require very long time horizons and cannot be solved by short-term thinking.”

Some people were quick to criticize the vehicle the couple is using to make their impact — a limited liability company instead of a traditional public charity or foundation. But the criticism is premature and shortsighted. Scholars and our better nonprofit leaders are coming to understand that new ideas about philanthropy are needed, that the world’s most difficult problems are going to need new approaches. While the traditional philanthropic model has resulted in remarkable social accomplishments, it is inadequate to addressing society’s most intractable and large-scale social problems. We need an addition, re-defined structure, and Chan and Zuckerberg may be doing exactly that.

Perhaps Zuckerberg comes to philanthropy naturally. First came the enormous wealth, even before Facebook went public. In 2010 he joined the Giving Pledge, a group of the world’s wealthiest people who have dedicated at least half of their fortune to philanthropy. (Currently there are 154 people who have committed to the pledge.) He was 29 when he joined, making him the youngest member at the time.

Despite what seems to be the gelling of his philanthropic thinking, Zuckerberg has had no roadmap. Our perception is still that those who give away vast sums of money do so in the context of years of worldly experience. Even Bill Gates, whose wealth also came relatively early on, worked longer to make his money and turn his attention to the broader needs of the world. Yet Zuckerberg and Chan are already consistently topping the lists of the world’s most generous philanthropists.

Still, it’s a learning process. In 2010, Zuckerberg devoted $100 million — his portion of a matching gift totaling $200 million — to help the failing schools in Newark, New Jersey. Dale Russakoff, who wrote “The Prize,” which details the gift and what turned out to be its disappointing impact, suggests that Zuckerberg learned that giving away money is a far more complex and humbling endeavor than he might have expected, a case study, Russakoff said, in the difficulty of translating good intentions into concrete results. Most of us tend to think $100 million can fix almost any problem. But in fact the scale of the problem in Newark dwarfed the size of the gift. In addition, the competing political and business priorities — to say nothing of the parents and children most affected (and, as it turns out, not much was said to them or on their behalf) — were overwhelming.

One key to understanding Zuckerberg, and perhaps it provides an insight to what drives his giving, might be that he can be described as a rebel, an anti-authoritarian. When he was still a high school student at Phillips Exeter Academy, he developed the Synapse Media Player, which would learn people’s music-listening habits. Although both Microsoft and AOL were interested in buying the program and in hiring him, he declined. College beckoned.

By the way, while Harvard was where Zuckerberg created Facebook, the story can actually be traced back to Exeter, which had something called The Photo Address Book so students could keep track of one another. Because the name doesn’t trip off the tongue with ease, for decades the students had been calling it “The Facebook.” In his senior year there, the school put the book online.

Another key, one that hints at an overarching thesis that brings together his business and philanthropic mindsets: Zuckerberg has said that what’s important in starting a company isn’t just to start a company but to “do something,” to go after problems and not do easy things, a philosophy that may have been the driver of his decision to go to college and rebuff offers from corporate America. “A lot of companies,” he once told students at Stanford University, “are operating on small problems.” The goal is to do something tangible. “The most interesting thing,” he said, “is to operate on something fundamental on how humans live. It was fundamental for me. I feel this need really acutely. I wanted this.”

He clearly wants a lot, and it looks like he has the intellect, passion and resources to make the world a better place.

We’re starting to see what that world will look like when the anti-authoritarian is the one in charge.

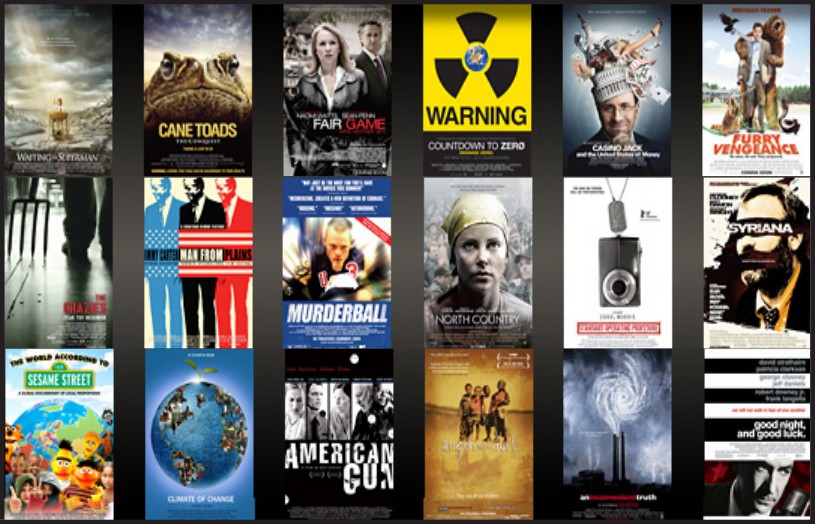

Robert Redford

By Doug White

The leading man casting Sundance's future.

Snowbound Buffalo, NY, would seem to be an unlikely venue for anyone—let alone an internationally-acclaimed movie star—to find his life’s inspiration. But it was there, stranded in a family-style Italian restaurant in 1970, that Robert Redford—fresh from the success of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid—learned that Hollywood was giving up Downhill Racer, a movie that only the critics loved. Redford, who starred in the film, was told to “let it go.”

Redford is a serious person. He loathes his handsome leading-man stereotype and, despite an iffy academic record—he was asked to leave the University of Colorado after he hosted a few drunken parties—he is articulate and thoughtful in interviews. One way to get a sense of him is to study the roles to which he has drawn. They are usually loners with heart, people who fight against the system. He once said, perhaps with some irony, that Downhill Racer was to have been the first of a trilogy about “the American mythology of success.” (The film has now entered the pantheon of American classics, and Redford’s own performance is widely praised.) The title of his 2013 movie, All is Lost, in which he is adrift on the Indian Ocean, silent and alone, says it all.

So it was typical of Redford to start thinking about what he could do to foster independent movies, which tend to be “D.O.A. in the world of Hollywood studios,” as he once observed. In 1981 he created the nonprofit Sundance Institute in Park City, Utah, an incubator for ideas that would never make it within the rigid formulas of the big studios. Since then, the Sundance Film Festival has become the premier outlet for high-quality independent films—and Redford the behind-the-scenes wizard who works its magic.

Although it isn’t a mega-charity, Sundance is substantial. It raises about $16 million every year and has an annual budget of almost $30 million, assets of about $38 million, and a $16 million endowment. It also stays true to its mission, to help the little guy (or gal)—a goal that Redford also helps achieve through the Sundance television channel for independent film and even the Sundance Catalog, whose sales of American crafts helps support new artists. In fact, in an era when many charities are searching for ways to grow and make better use of social media, Redford has publicly worried that the Sundance Film Festival, the most recognized of the institute’s programs, is getting too large and commercial.

Inevitably, Redford’s causes have infiltrated many of his movies. As the producer of The Motorcycle Diaries, a coming-of-age road movie about Che Guevera, he introduced Americans to some of the political and social issues of South America that shaped the revolutionary. He has also been an outspoken environmentalist, particularly for the Southwest (he has zealously protected from development the Utah property that he acquired nearly 50 years ago), and has promoted that cause through groups such as Greenpeace. Predictably, environmentalism has also found its way into some of the independent films and television programs in which he has played a role, either in front of or behind the camera.

Despite going down in a hail of bullets, it seems, the Sundance Kid may live forever.

Eileen Heisman

By Doug White

The CEO of the National Philanthropic Trust is going global with the brand and donor-advised funds.

“Charitable giving has a new look,” Time magazine recently reported, “one that is broadening the giving pool and helping keep the dollars rolling into nonprofits even during tough economic times.”

That new look is a method for giving called “donor-advised funds,” or DAFs. This is how it works: A donor opens an account at a “sponsoring organization,” such as a community trust or the charitable arm of a financial services company. While any contributions to the account are immediately tax-deductible, the donor generally has no deadline for disbursing the funds. It’s today’s go-to for philanthropists who aren’t ready to commit their wealth to specific organizations or don’t want the burden or expense of establishing their own foundation. DAFs, reports Giving USA, which tracks the annual growth of philanthropy, “are the fastest growing charitable vehicle in the country.” They have become so popular that they now represent more than $37 billion under management in the United States alone.

Technically, the DAF dates back to 1931, when The New York Community Trust invented the arrangement. However, not much happened for the next 60 years. “People didn’t realize the donor-advised fund model would work,” says Eileen Heisman, president and chief executive officer of National Philanthropic Trust (NPT). But in the early 1990s the Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund received a favorable ruling from a federal appeals court that said DAFs have charitable status, even when they’re under the aegis of an investment firm. Other groups quickly joined in.

Located in the Philadelphia suburb of Jenkintown, NPT, founded by the Pitcairn family in 1996, is today a DAF heavyweight. With more than $1.7 billion in charitable assets under management, NPT ranks among the 25 largest grant-making bodies in the U.S.

Heisman says that DAFs give donors the benefit of professional guidance. “Whether a donor wants to turn an illiquid asset into a gift or create a global grant or a multi-year grant, we hold a mirror up to what the donor wants and reflect best practices in the philanthropic world,” she says. That can include advice on how to structure the gift and outline its goals, as well as ongoing stewardship as donors regularly make their charitable decisions into the future.

But when it comes to how they want their money spent, donors “know what they want to do,” says Heisman. “Donors to DAFs are pretty well informed. They come in with a lot of energy about giving to their causes. They’re engaged philanthropically, many serve on charitable boards, and they’re using us as a way to fulfill their monetary philanthropic goals.”

Still, groups such as NPT do more than distribute alms. “Some people think a DAF is merely a wink for total [donor] control, but it’s really not,” Heisman notes. “Every document clearly states that NPT has the final say over how the money is to be spent. And we reinforce that verbally. We will honor requests that are legitimate, but if you want to go outside things that are legal then we won’t do it.” For example, a gift to an individual from a DAF is forbidden.

Although NPT’s donors are savvy, they still need to be reminded that their wishes might not stand the test of time. Heisman recommends that they include an escape clause in their gift agreements, permitting NPT, usually after a donor’s death, to spend the money on a similar cause if the original intent is no longer possible. “We have the obligation—and undertake the risk—to distribute the money properly,” Heisman says, “and we’ve seen so much that we almost always know more than donors when it comes to structuring the gift agreement. We also tell them that something might be legal now but the laws could change five years from now. Some donors embrace an escape clause in an instant. Others go kicking and screaming. If they never want to change any of their donative intent and if the purpose becomes obsolete, it’s going to be our job to figure something out.”

Congress and the IRS have long struggled with the concept of the donor-advised fund, and in the Pension Protection Act of 2006 Congress did clarify for the first time many definitions and regulations relating to DAFs. Still, the absence of a spending rule worries some legislators. Although foundations are required to spend at least five percent of their assets on their programmatic activities, public charities are not. So, the concern goes, DAFs are nothing more than parking lots where donors can stash money indefinitely and take healthy charitable deductions without actually helping society. The reason the charitable income tax deduction exists is to encourage people to give; the idea is that the foregone tax revenue will help society in ways that government cannot. So legislators might very well think there should be some minimum requirement to ensure that at least some of the deducted donations are actually injected into society’s bloodstream.

But that concern is misplaced, according to Heisman. “Donor-advised funds are actually paying out between 17 and 24 percent, and that doesn’t include overhead, as is the case with foundations,” she says. The National Philanthropic Trust conducts a lot of research on the model throughout the country, perhaps the most of any organization. “The issue about us being these warehouses is not warranted,” she adds. “Money is pouring out the door. We encourage philanthropy.” She sees no need for a required minimum annual payout. In fact, it could be counter-productive. “If you impose a five percent minimum, it may very well become a maximum in people’s minds. It actually could hamper giving. Why would you take a group of entities that are paying 20 percent and say you have to give out five percent per account when the aggregate is humongous?”

Heisman sees her biggest challenge, and perhaps NPT’s biggest opportunity, as one of shaping the future. While there’s no way private philanthropy can ever replace the government’s role in helping society, it can seed some interesting projects. She mentions NIH, the National Institutes for Health, which is a government agency. “NIH won’t fund anything without preliminary findings from smaller experiments, and private philanthropy often funds those smaller experiments. And not just in medicine. Private philanthropy can provide seed money for new ideas to emerge in many areas. “

A favorite teacher of Heisman’s once talked to her about “ideas coming from the fringe of society, and that when they mature they become mainstream.” Philanthropic money can be used to attack the root cause of a problem, not just the symptom. “You want to be funding the stuff on the fringe,” she says. “Some of it will become mainstream.” The women’s rights movement is another example. “There was a time,” Heisman says, “when women’s shelters were considered fringe organizations. Rape assistance? That was really radical. Now, nobody thinks they’re radical, but at the time it was difficult. Things shift and then people don’t even remember.”

When she talks with donors, she says she always tells them “not to be afraid of taking a risk. Some of the most creative thinking in the social sector is by people who are in emerging organizations. If the idea doesn’t mature, it doesn’t mean you were a failure. Maybe that idea could be the next big change in the social sector.”

At NPT, the next big change is expansion overseas and the organization is soon going to be offering the same services to donors outside the U.S. that it does domestically. To be sure, Great Britain’s philanthropic landscape is different from America’s. The federal government in the US as well as many state governments has passed legislation to actively promote charitable donations to a degree that few other nations have. It’s still unknown whether the British will take to the American approach, but it’s worth finding out. As Heisman counsels her donors, “Always take risks.”

Divorce

By Doug White

Learning from the Norton divorce.

Peter Norton, founder of the company whose ubiquitous computer software bears his name, sold his firm in 1990 to devote himself to philanthropy. With his wife, Eileen Harris Norton, he ran the Peter Norton Family Foundation, which has given heavily to arts organizations and some social-service groups. In 2000, Peter Norton filed for divorce. As often happens when a large fortune is at stake—Norton’s assets exceeded $100 million—the case was heavily litigated over a period of years. Eileen won the first round when a judge ruled that roughly 87 percent of the proceeds from the sale of the software company were to be considered community property, subject to equal division. One issue not on the table, however, was what would happen to the foundation.

This is an especially tricky subject. A foundation, strictly speaking, is not a marital asset—once money is donated, it is no longer under the personal control of the benefactors. Yet this is a grey area because influence over the foundation is, in a way, a fringe benefit of a marriage. That’s why many divorce attorneys will put the family foundation on the table during negotiations even though it is not a financial asset. “Say there’s a $100 million foundation,” explains William D. Zabel of Schulte Roth & Zabel in New York, a leading divorce lawyer to the rich and famous. “The husband says to the wife, ‘That’s it, you’re out, you have nothing more to say about it.’ I’d take that case in a minute.”

Virginia Esposito

Virginia EspositoThe confluence of two factors—the astonishing growth in the number of family foundations and a national divorce rate that continues to hover near 50 percent—suggests that family foundations will increasingly become an issue in divorce. “People are establishing foundations at a younger age,” says Virginia Esposito, president of the National Center for Family Philanthropy. “Everything in this founder generation is new. And changes in the family, happy or otherwise, are inevitable.”

Established in 1989, Norton's foundation had a market value of some $26 million by the end of 2002, a year in which it distributed more than 100 grants totaling $3 million. The biggest gifts went to the California Institute for the Arts, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Studio Museum of Harlem, and New York’s Symphony Space, which named its concert hall for Norton following a $5 million pledge. A one-time Buddhist monk, Norton has also made some offbeat philanthropic gestures, such as buying the notoriously personal letters written by the reclusive author J.D. Salinger to Joyce Maynard at auction from Sotheby’s for $156,000 and then returning them to their author.

After the divorce, a court order split the foundation 60/40 between the two, with, according to its 2011 IRS filing, a “substantial contraction.” A final return representing 2012 would be prepared, indicating that the foundation, which reported assets of only $50,000 in 2011, would shortly be out of business. Both Peter and Eileen continue to serve as trustees, along with Anne Etheridge, who is executive director.

Of the possible paths for family foundations caught in the middle of a divorce, some are exceedingly civilized. Virginia Esposito remembers an instance where both parties stayed on the board after the split. “They talked about it and decided that what they were doing transcended their personal problems, and now they seem to be doing just fine.” In another case, not only did both exes remain on the board, they were joined by their adult children and a new wife. “They realized the foundation was a part of their selves and have stayed focused on the work,” Esposito says. “It may not be personal property, but it’s part of their personal responsibility.”

Sometimes it’s important to give the participants “some breathing room,” she adds. “It may just be a matter of getting past the immediate difficulties. And you have to factor in the possibility that feelings might change. You could have the husband say, ‘I’m not that involved; you go on ahead with our adult children.’ Then, a few years later, he realizes there’s a space in his life and he wants to be more involved in his community.”

Of course, not everyone can be so calm and rational in the midst of divorce, and one option at the other extreme is to split the foundation in two. This isn’t terribly difficult as a technical matter, although there is some lawyering involved. “The basics aren’t that hard, but for people in that situation everything’s a big deal,” says Jerry J. McCoy, a Washington-based attorney specializing in charitable issues. “She says, ‘Most of the money was from my family,’ and he says, ‘But I tripled it in the boom,’ and she says, ‘But you tripled my money.’ It often degenerates into bitterness and that inability to get along.”

Karen Greene, who heads family foundation services at the Council on Foundations, recalls a number of occasions when a giving vehicle was rolled into two separate ones. For example, Norman Waitt Jr., who founded Gateway Computers with his brother Ted, later established the Andrea and Norman Waitt Jr. Foundation. After the Waitts’ divorce, the fund split into Norman’s Kind World Foundation and Andrea’s Messengers of Healing Winds Foundation.

Raoul Felder

Raoul FelderBut the same effect can be achieved more informally. “We frequently make claims that the wife has the right to direct a certain amount of foundation spending after the divorce,” says Raoul Felder, the dean of New York divorce lawyers. “As part of the settlement, the husband gives from his foundation to, say, the New York Community Trust, where she can set up something and control the spending. This is happening as people are getting more sophisticated.”

“Money is a socially prestigious weapon,” says Bill Zabel. “[Women] serve on boards where they have to make a $50,000 or $100,000 annual contribution. Take away that money and you’re causing tremendous harm to her social life. That’s why, in a majority of substantial divorce cases with a foundation, the departing spouse usually has an issue about how to share in the distribution. You can have a foundation giving away a million a year, and she might say, ‘I need $200,000 of that to keep up my contributions.’ So as part of the deal, you might give her the right to designate that amount. It’s usually done as a side letter, not as part of the public document, and the wife isn’t usually on the board after that – they want her out of there.”

Zabel has even seen foundations used for underhanded maneuvers in this realm: “Say a guy has $60 million, has been married 30 years and wants a divorce. So, he transfers $10 million to his foundation and says, ‘We have $50 million to split.’ Does he negotiate and give her certain rights to distribute that $10 million? Or does she say, ‘I should get $30 million, since he gave that money away knowing he would divorce me.’ It’s all arguable and negotiable and litigable. I don’t believe anyone’s ever litigated it—I’ve threatened to and settled—but it probably will be someday.”

The best way to avoid these sticky scenarios, experts say, is to think things through in advance. “When setting up a family foundation, you need to define what you mean by ‘family,’” advises Mary Philips of Grants Management Associates, Boston-based philanthropic consultants. “Set the criteria upfront so it doesn’t become personal. Make it clearly written: in the event of divorce, the divorcing spouse goes off the board—or not. Do we want only lineal descendents? Think of board eligibility in terms of your goals and the experience you want rather than who you want.”

“Ideally, families should treat eligibility in a fairly rigorous way,” says Karen Greene. “This applies not only to the founders, but to later generations. It seems inconceivable when it’s just you, the wife and the kids, but go down a couple generations and you’ve got 20 or 30 people. Someone’s divorced, another one never shows up at meetings. Do you just want lineal descendants? What about adopted children, stepchildren, offspring of gay and lesbian partners? Should your foundation exist in perpetuity, given how much families can change? It can be a ticklish situation, very uncomfortable if you’re the in-law who becomes the ‘out-law.’ It’s always better to make policy in the abstract, but you can’t foresee every circumstance. I remember one gentleman who came up and asked me, ‘How do I keep my daughter-in-law and get my son off the board?”

The Nortons are only one of many examples where philanthropists must think through all the implications of their divorce.

Reid Hoffman

By Kent Allen

LinkedIn's co-founder brings his venture capital savvy to philanthropy.

Even by the frenetic standards of Silicon Valley, Reid Hoffman, 47, is a busy man. He’s been at the center or on the periphery of dozens of start-ups, most prominently as a principal at PayPal and as co-founder of LinkedIn, the modern-day equivalents of—and now just as vital to life as—the personal check and the Rolodex. A venture capitalist who seems to have a finger in every tech pie, Hoffman is “the most connected man in Silicon Valley,” according to Forbes, which gives his net worth at upwards of $4 billion.

His involvement in nonprofits is as wide and deep as it is in his moneymaking enterprises, and he takes pains to apply the same ambition and business sensibility to the socially conscious organizations he supports. His intensity and the diversity of his interests are what you might expect from someone with a degree in symbolic systems (which focuses on different aspects of the human-computer relationship) from Stanford and a master’s in philosophy from Oxford.

In Hoffman’s nonprofit orbit of interest, a primary planet is Kiva, an unconventional “charity” that is more of a lending facility than a donative vehicle. The organization matches up lenders with borrowers for small-scale ventures.

Generally, the borrowers, who dot the landscape across the globe, have an idea for a small business but require as little as a few hundred dollars in startup capital. With few exceptions, they nearly always pay back the no-interest loan in its entirety after their businesses are in gear. While that track record is vital to the organization’s survival, Hoffman sees other benefits: Both lenders and borrowers, he believes, have an opportunity to learn how a small amount of money can make a big difference. He recently gave the organization $1 million so that thousands of would-be micro-lenders—who can invest as little as $25—could get a feel for the lending side of Kiva’s potential power. He is equally enthusiastic about the receiving end of the loans.

“The pattern you want is to empower people to invest in themselves,” Hoffman told TechCrunch, a blog about technology startups, in an interview last year in which he lauded Kiva for making small businesspeople out of ordinary folks who might not otherwise have the chance.

Hoffman takes a similar approach to other nonprofit organizations with which he’s been affiliated, including Do-Something and Endeavor Global. Do-Something resembles Kiva but targets young lenders specifically. Its generation-next edginess was apparent recently on its website: “Join over 2.2 million people taking action,” it urged. “Why? Because apathy sucks.”

By contrast, Endeavor Global, while a nonprofit, is not a charity. It matches up successful businesspeople with prospective entrepreneurs in a mentoring program. Hoffman himself takes on the role of mentor. In a posting on the organization’s website, he offered his “top 10 rules of entrepreneurship.” They included “aim big,” “maintain flexible persistence,” and “look for disruptive change.”

Hoffman says that in college he decided he wanted to try to influence the state of the world on a large scale. “My plan was to become a professor and public intellectual,” he told Director magazine a few years ago. “That is not about quoting Kant. It’s about holding up a lens to society and asking, ‘Who are we?’ and ‘Who should we be, as individuals and a society?’’’ But he soon determined that he could make a greater impact as an entrepreneur—and now he’s trying to help others do the same.

Nexus

By Jay Balfour

A series of international events aims to catalyze philanthropy in young wealth holders.

Philanthropy is rarely a young person’s game. Tech innovators and entertainers aside, those who can afford to give headline-grabbing sums generally do so later in life, towards the end of a career or in retirement. And with the millennial generation often stereotyped as unemployed, unmotivated, and generally adrift, it would seem unrealistic to look to them for buckets of cash. But next-generation philanthropists aren’t waiting for wealth, and their enthusiasm may be their greatest asset.

In July 2013 about 700 people, most of them young, gathered at the United Nations Headquarters in New York for a global youth summit on innovative philanthropy and social entrepreneurship. The organizing body, Nexus, was founded a couple years prior in partnership with the UN and other governments in an effort to involve young people in a global culture of philanthropy. That year's summit, Nexus’ third, was easily its largest and most exuberant up to that point.

What distinguished this gathering from, say, a dinner of Giving Pledge signatories, however, was not the number of zeroes before a decimal; it was a fundamentally different approach to giving. “I think people in our generation see the term ‘philanthropist’ as a passive term,” Nexus cofounder Rachel Cohen Gerrol said in an interview with Giving Magazine, “like, ‘I’m a check writer,’ and they feel that much of the value they have to offer is not located in their checkbook. If you go back to the larger sense of ‘philanthropist’ as a caretaker or lover of humanity, that would be much more in line with how people would define themselves.”

That’s true even of young attendees who actually have access to a checkbook, such as Zac Russell, the youngest and only next generation member of the board of the Russell Family Foundation (which has an endowment of roughly $135 million). Like many of his peers, Russell has a broader definition of what it means to be a donor. “‘Philanthropy’ means money in modern contemporary [terms], but I think of it as time,” he said during the summit. “I think of it as intention, of making the world possible that you want to see by your actions. It just so happens that in our contemporary world money relates to action.”

In connecting money to action, Russell is in good company at Nexus. “We’ve made this shift from philanthropic giving to philanthropic living for this community,” Gerrol said, “and that means that you’re voting with your dollars every time you purchase a candy bar or a purse just as much as you are when you decide where to write your foundation check to or what you do professionally.” (Notably, the conference gave out goodie bags stuffed with Kind cereal bars and “ethical” treats from Taza Chocolate and Kopali Organics.)

Perhaps nowhere was this concept better embodied than in a conversation during the summit between Kenneth Cole, better known as a designer than as an activist, and his daughter about fashionable philanthropy and clever social marketing. (Cole’s products—“be awear” bracelets, “hot in here” T-shirts about climate change—have garnered publicity and raised funds for causes for years.) In fact, one of the strengths of Nexus’ summits is their ability, as a watering hole for the upscale young, to attract bold-face names. Adrian Grenier, environmentalist and star of the popular HBO show Entourage, helped draw a crowd the first morning. By contrast, veteran civil rights activist and singer Harry Belafonte attracted about 30 attendees and issued a call to action on more ‘60s-style terms. He also added a note of deja-vu. “I’ve been before you before, Nexus,” he said, “because among a number of titles, I’ve also been a beggar. I don’t like it, it tampers with my dignity, but it’s a necessity. What bothers me is how often we have to beg for the same money, for the same cause.”

The distinction between traditional philanthropy and social or impact investing—and the issue of which is the more effective path forward—was reflected throughout the summit. Ladislav Kossar, the manager of a philanthropic investment group in Eastern Europe, asked attendees to place their own endeavors on a spectrum, from “pure philanthropy” to investments with an expectation of financial return. The response resulted in a watershed moment: It became evident that the room was full of entrepreneurs and self-starters, not traditional givers.

Judging from such measures, young people at the summit were the actors rather than the funders of change. Heirs such as Zac Russell were far outnumbered by ambitious entrepreneurs that need money like his family’s, and the summit is less an explicit bridge between the two than it is a meeting ground. At the same time, as Gerrol noted, many participants wear more than one hat. For example, she pointed to Lana Volfstun, who is the executive director of One Percent Foundation, which is trying to encourage giving circles and philanthropy within the millennial generation; she is also from a very philanthropic family and has been involved with two programs for young philanthropists in the Jewish community. “She might come off as a social entrepreneur, but she’s also a philanthropist,” Gerrol noted.

A Nexus delegation.

A Nexus delegation.Of the dozens of panel discussions, most were on issue-driven topics related to equality and awareness, with names like “How Pop Culture Can Drive Social Change” and “Women and Girls.” Yet there were also a few breakaway sessions for current and prospective possessors of wealth: “Taking on a Role in the Family Foundation” and “How to Distinguish Oneself When a Parent’s Legacy Casts a Wide Shadow.”

It’s likely that Nexus’ future lies in its potential for breaking down walls between the askers and the givers in its own ranks. For now, the summits have done an impressive job in sparking a dialogue—and with it the recognition that some of this dialogue has been held before. “These are conversations that were percolating in the hallways and the hidden corners of conferences about similar issues twenty or thirty years ago,” Gerrol noted. “If you look at who were the students in the ‘60s, they were radicals and revolutionaries, and they are now people in their sixties today. I think as we build a movement of youth, we need to be standing on the shoulders of those who laid the foundation for this movement to exist, and to learn from them.” For today’s older donors, that could be as good as it gets.

Don & Mera Rubell

By Holly Howe

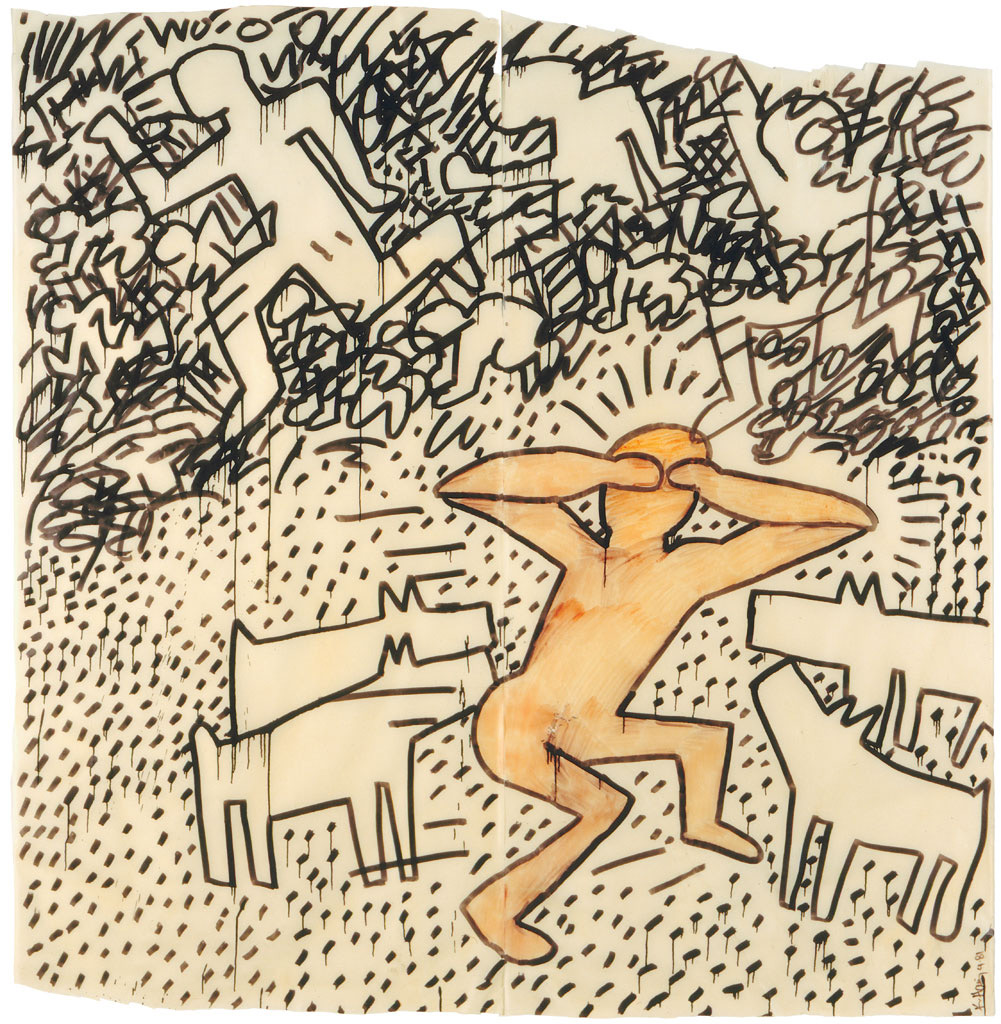

The Miami-based couple think of themselves as custodians with a grand purpose, sharing their 5,000-piece modern art collection with the world.

What to do when you have an art collection with over 5,000 pieces, including works by Keith Haring, Paul McCarthy and Jeff Koons? Share it with the world, according to Don and Mera Rubell, the Florida-based visual-art power couple. “You discover very quickly on this journey that you’re just the custodian of the important cultural artifacts of our time,” Mera once noted, in an interview with the Financial Times. “So how could you not make them available to the public?”

The Rubells never worked in the creative industries; Don, 74, is a retired gynecologist and Mera, 71, is former president of sportswear company Ellesse. But when they started dating, after meeting in the library of Brooklyn College in 1962, they discovered a shared passion for art and together explored artists’ studios and galleries in their free time. Initially there wasn’t much money to buy art—Don was in medical school and Mera worked as a teacher—but they allocated $25 a month from their $100-a-week income and set up the Rubell Family Collection shortly after they married in 1964. When Don’s brother, Studio 54 cofounder Steve Rubell, died in 1989, the Rubells inherited assets estimated to be worth $200 million. They sold those, freeing up cash to invest in hotel real estate and contemporary art.

Today, they have amassed what is widely regarded as one of the most important and edgiest private collections of contemporary art in the world. They are still collecting, an undertaking to which they devote about a quarter of their money. And, more than ever, it has become a family affair, particularly since their son Jason joined the board, and all three have to agree on a piece before they acquire it. (Their daughter Jennifer, an artist herself, opted out of the process to avoid any conflict of interest and to focus on her own career.)

In 1993, they took over a disused 45,000-square-foot facility in Miami where the Drug Enforcement Agency had housed confiscated goods, converted it into a 27-room museum and opened it to the public. The building displays some of their collection as well as their library of over 30,000 art tomes.

The Rubells see the museum as a way to educate people about contemporary art. “The major contribution of these private/public collections is it fills the gap for young people to see the art that’s being made today,” Don stated in an interview with the Art Economist. “I remember when our kids went to Duke and Harvard, and both of their art history courses ended with Andy Warhol... It’s a twenty-year lag. The young people never see what’s being produced that relates to their issues and passions.”

Staging exhibitions at most publicly-funded museums can be an arduous and time-consuming process, but the Rubell Family Collection has the agility to put a show together in a matter of months, and can display new acquisitions quickly. They also regularly loan items from their collection to other museums, and even transport entire exhibitions from their own museum to other institutions, such as the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington DC, and Fundación Banco Santander in Madrid.

But not everyone has welcomed the Rubells’ gifts. In the early 1980s, Don wanted to set up an art bequest with his alma mater, Cornell University, but the school’s art museum declined the gift, citing lack of space. A few years later, when Cornell reconsidered the offer and went back to the Rubells, administrators discovered it was no longer on the table. A shame, as they missed out on works by the likes of Jean–Michel Basquiat and Cindy Sherman.

Haldun Tashman

By Sandra Salmans

Exporting the community foundation model, entrepreneur Haldun Tashman is connecting the Turkish diaspora through interest-based giving.

When Haldun Tashman, a Turkish-born entrepreneur living in Arizona, hears about another successful Turkish-American like himself, he feels more than a glow of kinship, he makes a note. Tashman, 69, is the founding chairman of Turkish Philanthropies Fund (TPF), a New York-headquartered community foundation that seeks to recruit potential donors in the U.S. and connect them to social projects, primarily in Turkey.

Tashman established TPF almost nine years ago, when the sale of a medical supplies business he’d built in Phoenix allowed him to pursue his passion. Having earned an MBA at Columbia as a Fulbright Foreign Student Fellow in 1968, in 2003 he created the Tashman Fellows program, which provides support for young Turkish or Turkish-American MBA students. But he wanted to do more, and his experience as a trustee of Arizona Community Foundation showed him how. He commissioned one of his bright young Tashman MBAs to conduct a feasibility study and, encouraged by the results and the examples of funds established by the diaspora of many other countries, formed TPF, to promote philanthropy among Turkish- Americans. At the same time, he and his wife, Nihal, established the first community foundation of Turkey in his hometown, Bolu.

In the years since Tashman and his three partners founded TPF, it has raised more than $16 million, of which it has distributed more than $11 million in grants. Most of the funds go to education, much of it specifically to gender equality programs designed to educate and empower women and girls. Like all community funds, TPF offers advantages to philanthropists who choose that route: it screens nonprofits to advise donors about where to make the best social investments; follows up to ensure the funds have been properly used; and handles the onerous paperwork that can defeat the most committed philanthropist; to do this, Tashman travels in a continual loop between Phoenix, New York, and Istanbul.

TPF money has gone to build village schools, provide disaster relief after the earthquake in eastern Turkey in 2010, and support traditional rugmaking in Anatolia. One donor in New York, rather than throwing a birthday party for her daughter, raised $20,000 to buy books for girls in Turkey, Tashman notes. In Bolu, the Tashmans are using their own community foundation to support the development of an infrastructure for philanthropy, as well as an early-education project. “There are foundations in Turkey, but everybody wants to do their own thing,” says Tashman, who hopes to bring people together to share best practices and give more strategically.

But to thrive, he notes, TPF must recruit the next generation of Turkish-Americans. TPF has a junior board of younger directors, U.S.-educated professionals with dazzling credentials. One of the Tashmans’ daughters is a donor to TPF, and Tashman believes he is providing seed capital through his fellowships. By the time the fellowship program wraps up, he estimates, it will have sent 50 fellows out into the world. “I’m looking for one or two who will be very successful and will do great things in philanthropy,” Tashman says, “and I’ll feel, mission accomplished.”

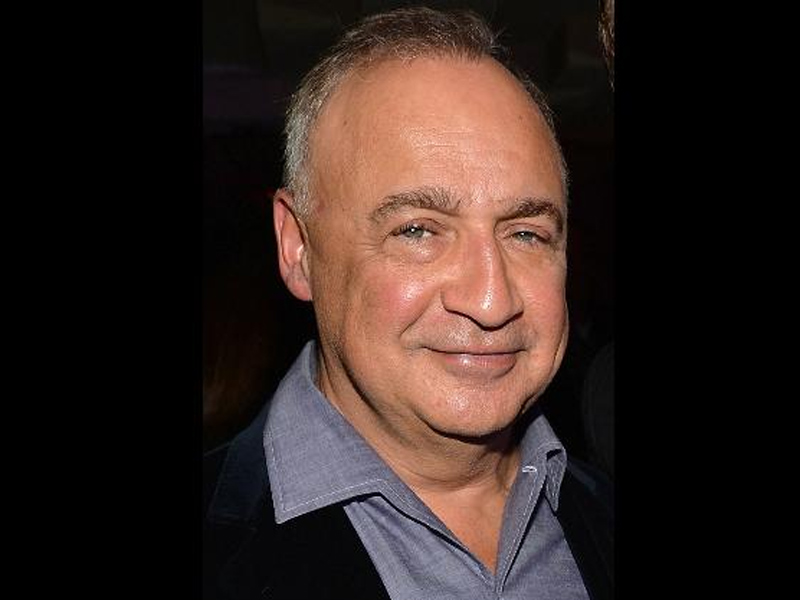

Len Blavatnik

By Doug White

A Soviet emigrant to the US, Blavatnik is becoming a generous establishmentarian in education and beyond.

“Leonard Blavatnik is making possible a new way for Oxford to contribute to the world.” So began the September 2010 tribute by Lord Christopher Patten, Chancellor of the University of Oxford, in his remarks acknowledging Blavatnik’s “once-in-a-century” $120 million gift, which established Europe’s first major school of government at the oldest university in the English-speaking world.

Blavatnik, like many other donors with an eye on making transformational gifts, is not new to philanthropy.

Through his family foundation, he recently donated $50 million to fund the “Blavatnik Award for Young Scientists” at the New York Academy of Sciences. The money is helping to expand the number of people who are eligible to receive the award, which will now be open to faculty-rank scientists across the United States age 42 or under. The idea of “young” is key. According to Eric Lander, a director of the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, “Young scientists drive scientific discovery and innovation. They feel urgency and impatience. They think creatively and boldly. While we must support promising scientists at all levels, young scientists are a critical resource that we must nurture for the good of the whole scientific enterprise.”

But while academic pursuits feed the mind and eventually improve lives, Blavatnik is also putting his money where it will have immediate impact on people who desperately need it. He gives much every year to Colel Chabad, an Israeli charity that operates a network of soup kitchens and food banks, dental and medical clinics, daycare centers, widow and orphan support, and immigrant assistance programs. Founded in 1788, Colel Chabad is the oldest continuously operating charitable organization in Israel. Blavatnik’s support provides food every month for 5,000 families in 25 Israeli cities and towns.

In 1978, during a period of mass emigration for Soviet Jews, Blavatnik left his home in the Soviet Union for the United States. After then earning advanced degrees at Columbia and Harvard, his business career took off. He founded and is chair of Access Industries, a privately held multi-national company headquartered in New York, that invests in natural resources and chemicals, media and telecommunications, and real estate. In 2011 a subsidiary of Access bought the Warner Music Group for $3.3 billion.

As his generosity shows, Blavatnik tends not to think of starting new charitable enterprises; what makes his gifts noteworthy is his well-funded focus on improving what’s already working. There might be no better example, and thus an explanation for his comfort in giving away so much of his wealth, than his bet on one of the world’s premier educational institutions—a grand gesture meant to fuse history with the future. In Lord Patten’s words: “Oxford will now become the world’s leading center for the training of future leaders in government and public policy—and in ways that take proper account of the very different traditions, institutions and cultures that those leaders will serve. It is an important moment for the future of good government throughout the world.”

True enough. But even so, his gifts might say as much about the man, and his vision of what’s right in the world, as it does about the institutions that he supports.

The Top People

By Nelson Aldrich, Jr

The fate of almost everything that's good, true and beautiful in America is in the hands of that exclusive group called trustees.

Do you remember Jean-Marie Messier? A little over a decade ago, in New York City’s philanthropic circles, the then chief executive of the Franco-American company Universal-Vivendi was the toast of the town. Literally (in that fund-raising season Messier was toasted at benefits for the New York Public Library, the Appeal of Conscience Foundation, and the Robin Hood Foundation) and figuratively speaking, too. At the time the Whitney Museum and the Museum of Radio and Television had made him a trustee; he was being considered for the board of the Metropolitan Opera; and his wife, Antoinette, was on the board of the New York Philharmonic. Less than a year later, with Universal-Vivendi’s stock in free fall and his own corporate vainglory under harsh scrutiny in Paris and New York, Jean-Marie Messier was toast. The moral of the Messier story was summed up by the woman who had wooed him for the board of the New York Public Library, Elizabeth Rohatyn, wife of the investment banker and former ambassador to France, Felix Rohatyn, and herself a notably public-spirited figure in the city. “When new top people come to New York, everybody wants them,” she said.

Let’s unpack that. “Top people” is an obviously enviable social niche. We all want to be ‘at the top’ in some category or other—a top dermatologist, say, or a top golfer at the club, or a top government official, or a top stamp collector. But to be among the top people is a different kind of wonder.

Jean-Marie Messier