About

Global Team

Roberta d’Eustachio

Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Roberta d'Eustachio (Rd'E) is an entrepreneur obsessed with delivering media from the social investor/philanthropist's point of view. That desire led to founding The American Benefactor, the first consumer magazine for philanthropists, as well as Giving Magazine and each of its subsequent evolutions: from print, to digital, to mobile with Facebook Instant Articles, delivering stories of social impact - for everyone, everywhere.

Rd'E has consulted with, and/or received investment from, leading global brands, including: The Economist, the Financial Times, Euro Money/Institutional Investor, the Pitcairn Family Office, Fidelity Capital and the World Bank as well as philanthropists and social enterprises around the world.

After serving as chief-of-staff to Dame Stephanie Shirley, the British Government’s Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy, Rd'E founded the AmbassadorsForPhilanthropy.com enterprise to give social investors a voice worldwide.

Dame Stephanie Shirley

Philanthropist & Believer-in-chief

Dame Stephanie “Steve” Shirley is a British entrepreneur turned philanthropist. She originally arrived in London as an unaccompanied Kindertransport child refugee from Austria during WWII. “Steve” was an early pioneer in technology and, after taking her company public, she has given more than $100 million to organizations that specialize in autism research and technology, including founding the Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University. Appointed by Prime Minister Gordon Brown to the title of the British Government's Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy 2009-2010, she believes in the advancement of the philanthropist voice worldwide.

Her memoir “Let It Go” was recently published, chronicling her life so far.

"Steve" is the Believer-in-chief to Giving Magazine, providing the means to imagine and execute its potential to the fullest.

Jerry Alten

Chief Curator

Jerry Alten is a world-renowned art director of magazines, across all devices, and other marketing and advertising work, winning many prizes in the media field. Under Walter Annenberg’s ownership of TV Guide, Jerry took the circulation from 5 million up to 19 million during his tenure as art director. He continued to work with Rupert Murdoch’s organization after the buy out of TV Guide and created the first interactive website for the magazine. Jerry was also the original investor in The American Benefactor Magazine and art director, which succeeded in obtaining more than $7 million worth of investment from Fidelity Investment's venture firm.

Brian Lipscomb

Chief Technologist

Brian Lipscomb has been involved with technology for over twenty years, and founded technology services company Divergex, based in Philadelphia. Specializing in all aspects of computers, Brian brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to Giving Magazine. His philosophy is: “Do it right, or don’t do it at all.”

Lipscomb adds: “Technology is a constantly evolving industry. People who use technology daily don’t have the time to study and learn all of the new and different terms and capabilities. I work to show people how technology can improve their efficiency, productivity and, ultimately, their lives.”

Jay Balfour

Managing Editor

Before Jay became the Managing Editor for Giving, he was a freelance writer and editor based in Philadelphia. With an academic background in Philosophy he leverages an informed perspective on everything from African music to youth movements in the West for several publications both online and in print. At Giving Magazine he shares a passion for unabated reporting and the ushering in of a new age in philanthropy.

Sandra Salmans

Executive Editor

Sandra Salmans is a New york-based writer and editor who works primarily in the nonprofit field. She began her career as a business and financial journalist at Newsweek and The New York Times, but has also covered national news, education and the arts. Prior to going freelance, she was a senior officer in communications for a leading foundation in Philadelphia.

Nicole Raeder

Digital Design Manager

Nicole delights in great design. That's why her commitment is compulsive; contagious even, to get it right. Or, change it. Or, change it again. Whatever is required to finding the way to the end point, which is sometimes the beginning. In other words, she never gives up, or stops, till the thing clicks.

She also loves cats.

Damon d'Eustachio

Co-Director, Global Membership

A foodie who navigated his way from the city of brotherly love to Charleston, S.C, Damon is devoted to serving nonprofits worldwide that believe the philanthropist voice must be heard.

Damon graduated from the College of Charleston in Art Administration and performed an internship at London’s prestigious Tate Gallery’s New York City office.

Jessica Lambrakos

Co-Director, Global Membership

Jessica is responsible for the management and development of the Global Awards for nonprofits of Giving Magazine for their nominated philanthropists and supporters.

She also serves as founder and executive director of her own nonprofit, “The Naked Truth AIDS Project”, which raises funds for AIDS prevention education programs in the USA as well as Africa.

Nick Cater

Contributing Editor

Nick Cater is a UK-based international writer and editor. A former Fleet Street journalist, he has reported from more than 40 countries so far on stories as diverse as war in Africa, environmental risks in Latin America, disasters in Europe, and the Asian sport of elephant polo.

Luke Norman

Senior Editor

Luke Norman is an experienced journalist and corporate social responsibility consultant. Having started at The Daily Telegraph, Luke has worked for a wide range of international media outlets before moving into the heady world of multi-national corporations and their sustainability commitments. Luke has transplanted himself and his family from London to Rio de Janeiro, where the views he now observes are deliriously engaging.

Doug White

Senior Editor

Doug White, a long-time leader in the nation's philanthropic community, is an author, professor, and an advisor to nonprofit organizations and philanthropists. He is the director of Columbia University's Master of Science in Fundraising Management program. He also teaches board governance, ethics and fundraising. His most recent book, “Abusing Donor Intent,” chronicles the historic lawsuit brought against Princeton University by the children of Charles and Marie Robertson, the couple who donated $35 million in 1961 to endow the graduate program at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Kent Allen

Journalist

Kent Allen is a longtime daily journalist and freelance writer. Over the past 20 years, while also writing about philanthropy and nonprofits, he has worked as an editor at The Washington Post, U.S. News & World Report and Congressional Quarterly. At present, Kent is a journalism and history teacher at The Field School, a middle and high school in Washington, D.C.

Lucy Bernholz

Journalist

Lucy Bernholz is a blogger and self-proclaimed “philanthropy wonk”. Her blog, Philanthropy 2173: The future of good, has been named a “best blog” by Fast Company and a “philanthropy game changer” by the Huffington Post.

Kim Breslin

Actor

Kim Breslin is an actress, comedienne, director, producer, artist, and chef. She has been an educator in North Philadelphia for 17 Years. Mother of two incredible children, she lives with her highly supportive cat, The Amazing Sid.

Cheryl Chapman

Journalist

Cheryl Chapman actively promotes philanthropy in the UK and globally via her journalism. She was the editor of Philanthopy UK: Inspiring Giving and now heads City Philanthropy, London, as its Director.

Stephen Dunn

Poet

Stephen Dunn, Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, is the author of 11 collections of poems, including “Different Hours,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 2001.

Regan Good

Poet

Regan Good is a freelance writer and poet living in Brooklyn, New York. She has written for The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times Magazine and others. She is currently at work on a memoir about growing up in a family of writers.

Sharilyn Hale

Journalist

Sharilyn Hale, M.A., CFRE is Founder and Principal of Watermark Philanthropic Advising where she offers strategies for meaningful giving, receiving and leading. A practitioner, author and educator, she brings a global perspective on philanthropy having served the nonprofit sector across North America, Bermuda and the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. She holds a graduate degree in Philanthropy & Development and is past Chair of CFRE International, the global certification for professional fundraisers setting standards for ethical and accountable practices.

Crystal Hayling

Journalist

Believer in a better world. Uppity advocate for social change. Former philanthrapoid. Crystal lives in Singapore where she helps donors develop strategy for effective grantmaking. She serves on numerous boards, and is a speaker and writer on civil society. Twitter: chayling

Holly Howe

Journalist

Holly Howe is a strategic communications consultant with a particular focus on the arts. She works as a freelance journalist, writing for various publications including FAD, RWD, House (published by the Soho House group) and the Irish Examiner. She also runs the Culture Vultures, a networking group for people in media and the arts. She can be found tweeting at @ hollytorious and in her occasional spare moments, she posts on her blog www.postcardsfromholly.blogspot.com

Wangsheng Li

Journalist

Wangsheng Li is president of ZeShan Foundation (Hong Kong) and a Senior Fellow of the Synergos Institute (New York City).

Lisa Macdonald

Journalist

Lisa MacDonald is a freelance writer and editor based in Toronto. A passion for philanthropy drives her involvement in initiatives that bring information and innovative ideas to Canada’s nonprofit sector leaders. Tweet her at @lisalmacdonald.

Andrew MacLarty

Actor

Andrew MacLarty is a New York based actor who has appeared on Boardwalk Empire and White Collar. Non-profit work includes narration for Partnership for a Drug-Free America, performances at the United Nations for Hurricane Katrina relief benefit shows, and Barefoot Theater Company’s ROCKAWAY benefit for Hurricane Sandy victims.

Bruce Makous

Journalist

Bruce Makous, ChFC, CAP, CFRE, has been a professional fundraiser for over twenty-seven years, with leadership positions in major educational, healthcare, and arts organizations. In 2009, he was named by the Nonprofit Times one of the “Most Influential and Effective” fundraisers in the US.

Peter D. Michael

Actor

For over 20 years, Peter D. Michael has been an established actor, voiceover talent and stand-up comedian. He is also an Emmy award winner.

Suzanne Reisman

Journalist

Suzanne is a U.S. international private client lawyer based in London. Suzanne assists philanthropists, their foundations, and international charities with cross-border philanthropy.

Julie Shafer

Journalist

Founder of Julie Shafer Development + Philanthropy, a national philanthropy consulting firm. Ms. Shafer offers a multifaceted skill set honed throughout 20 years as a philanthropy executive bringing a translational approach that bridges the gaps between philanthropists and non-profits.

Jade Shames

Playwright

Jade Shames is an award-winning writer living in Brooklyn, NY. His work can be found in The Best American Poetry blog, The LA Weekly, HOW art and literary journal, and more. He was awarded a creative writing scholarship to attend The New School where he received his MFA.

Amy Singer

Journalist

Amy Singer teaches Ottoman and Turkish history, as well as courses on Islamic philanthropy and the history of charity in the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University. Her recent publications include the book "Charity in Islamic Societies", and in 2008 she was awarded the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Award.

Sharit Tarabay

Artist

Sharit Tarabay painted the portrait of Gerry Lenfest. He is a painter and illustrator living in Montreal. He has his works published in magazines and books around the world.

James V. Toscano

Journalist

Jim Toscano is a principal in the consulting firm, Toscano Advisors, LLC, and an adjunct professor at the School of Business, Hamline University. Recently retired as president of the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, the cardiovascular research and education center of Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, he is a past chair of the Minnesota Charities Review Council and board member of Minnesota Council of Nonprofits.

Susan Yu

Journalist

Susan Yu is a journalist from the San Francisco Bay Area. She is an award-winning news reporter who was formerly based in Hong Kong for 14 years covering stories in Asia for international news media organisations. She is currently based in the United Kingdom where she freelances as a writer, editor and documentary film producer.

The Bipolar Nature of Philanthropy in Hong Kong

By Susan Yu & Luke Norman

With one of the highest concentrations of millionaires in the world, Hong Kong's philanthropic industry is still growing. But despite big donations, the city's giving remains a quiet affair.

The protests and widespread student demonstrations that made headlines through the end of last year marked Hong Kong indelibly as a city in-between. An unabashed beacon of over-the-top 21st-century capitalism, Hong Kong’s putative manager, Leung Chun-ying, is known not as “the mayor” but as the city’s chief executive. Leung currently faces increasing opposition and calls for resignation as the representative of Beijing politics, yet under a recent ruling candidates for his job must be nominated by committee, effectively stifling the city’s hopes of self-governance.

While the ongoing unrest is recent, the rift between Hong Kong and mainland China is long-standing and has made the city one of the most politically complex places in the world.

Not surprisingly, similar polarities mark Hong Kong’s approach to philanthropy.

As the world’s ninth-largest economy, with more billionaires in its 426 square miles than in the whole of the UK, Hong Kong is an ideal host to thriving philanthropy: government social services are widely considered underfunded, income disparity is growing, and the underclass is crying out for attention.

Yet in Hong Kong, philanthropy keeps a mostly low profile. The silence and apparent fear of engagement that characterize the city's philanthropy are less a reflection of a dormant industry than a purposefully quiet one. From the long-running Tung Wah Hospital to newly innovative social entrepreneurism, philanthropic examples abound, but few practitioners seem to have any desire to talk about them. There may be more than 7,200 nonprofits in Hong Kong and donations in 2010-2011 topped $1.2 billion—with more than two-thirds of residents dipping their hand into their pockets—but philanthropists willing to go public are thin on the ground, especially considering that high-value gifts dominate the scene.

Gifts from middle-class donors in the city are still growing, but in 2012 alone, “104 donations worth $1m or more were identified in Hong Kong...with a combined value of $877m” according to a recent Coutts report. Most recently, Ronnie Chan, a property tycoon who shares his $3.2 billion net worth with younger brother Gerald, made headlines for a $350 million gift to Harvard, catching flak for supporting a university that was not only American but already well-endowed. As the recent Chan family trust donation bears out, Hong Kong’s philanthropists are not always quiet, but increasingly donor-critical public opinion shows why they might want to be.

Sir Michael Kadoorie

Sir Michael KadoorieThe work of the Kadoorie dynasty, one of the richest and most famous families in Hong Kong, is a good example of the sector’s low-key style. More than 60 years ago, the Kadoorie Agricultural Aid Association was established as a community service for Chinese refugees spilling into Hong Kong from the Communist mainland. Over time the association morphed into the Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden, which now engages in environmental and conservation research.

With the growth of the Kadoorie fortune, its philanthropy has apparently diversified. Thanks to the family-run China Light & Power Company, along with the Hong Kong & Shanghai Hotel Group, the current scion, Sir Michael Kadoorie, landed the 115th spot on the 2013 Forbes Rich List, with a reported personal fortune of $9.5 billion. The Kadoorie Charitable Trust, founded in 1997, now directs most of Sir Michael’s philanthropy, supporting projects in China and throughout South and Southeast Asia. Still, a lack of public records makes it impossible to gauge its activities and a director of the Trust quietly explains, “The family doesn’t normally give interviews."

In fact, Sir Michael and the Kadoories have plenty of company. Sir Run Run Shaw, the famous movie maker and television magnate who passed away at 107 early this year, Sir Joseph Hotung and his older brother Eric Hotung, and Dr. Hari Harilela—a who’s who of Hong Kong’s recent heavyweights—are all entrenched in a generous but anonymous culture of giving.

That culture may be a product in part of the city's entangled religious past--ancient and largely culturally Buddhist, on one hand and more recently Christian due to British colonialists, on the other. More practically, there’s also an obvious financial motivation behind Hong Kong’s blockbuster giving: philanthropists get a tax break for their donations, so they may want to downplay their gain.

Bernard Charnwut Chan

Bernard Charnwut ChanStill other issues may factor into the pervasive secrecy. “Safety is the first thing that is in people’s minds,” Bernard Charnwut Chan says. Chan is a fourth-generation heir to a Hong Kong-by-way-of-Thailand fortune who also serves as Vice Chairman of Oxfam's regional operations. “It is the low-profile high-net-worth people who do not want to publicize their giving,” he adds. “Another reason is that they don’t want people to keep bugging them. Once they know you are a giver, the next thing you know you will have private bankers, lawyers and charities coming after you. So they like giving but they don’t want to advertise this and be chased.”

This keep-your-head-down approach isn't surprising in light of Hong Kong's continuing political unrest, with democracy protesters still blocking off access to some of the city's most expensive real estate as a part of ongoing demonstrations. In 2012, at the height of recent growth, the number of the city's millionaires rose by 40 percent. It rose by 27 percent over the last five years, according to a recent Wall Street Journal report. (At last count, Hong Kong ranked 20th in a list of countries with the highest number of millionaires.) Carry on up the ladder and the four richest men in Asia, with a combined wealth of $90 billion—Li Ka-shing, Lee Shau-kee, Lui Che Woo, and Cheng Yu-tung—all call Hong Kong home. By contrast, a recent study by the city’s chief executive’s office found that one in five residents lives in poverty; the region’s Gini Coefficient, a measure sometimes used to predict the potential for social unrest, also climbed into the danger zone in recent analyses.

For a city economy that is now based almost exclusively on high finance and real estate, there is little provision for a growing and increasingly vocal underclass. With the introduction of a city-wide minimum wage in 2011, some of Hong Kong’s last manufacturers fled for the cheaper, neighboring province of Guangdong to the north. Leung, who came into office vowing to reduce the record wealth gap, is trying to help the poor by increasing welfare spending, giving tax incentives to more than 400,000 OAPs (old age pensioners) and rekindling a long dormant policy permitting the subsidized sale of public housing. Backlash against Leung in recent weeks has been anchored in unrest over the near-future prospects of self-governance in Hong Kong as student groups blame the chief executive for mischaracterizing legislation that will require democratic candidates to be nominated by committee. But the form of protests has shown repeatedly that class division remains central to the discontent.

James Chen

James ChenIn the meantime, a few of Hong Kong’s philanthropists are seeking their own solutions and encouraging others to do the same. James Chen is the chairman of the Chen Yet-Sen Family Foundation, which has funded more than 150 social initiatives in Hong Kong, China, and West Africa. The foundation’s activities are unusual for being mostly public and uncommonly traceable.

“Part of our leverage is being able to reach out to other families,” Chen says. “It is about celebrating the successes and learning from the failures not only for us but for the wider community. Other wealthy families inclined to support philanthropy might have a different model to look at and to see what could be done.”

Initially, Chen recalls, his foundation chose a traditional, private route, even disdaining a website for its first few years. The change came with the realization that as positive news started to trickle back from beneficiaries to the funders, other potential stakeholders pricked up their ears and got on the telephone. The more successful the foundation became publicly, the more it was approached by interested philanthropists. Now, it not only supports active social projects, but also backs informal capacity-building gatherings in Hong Kong and China to enable nonprofits, volunteer groups, and individuals to similarly share information.

“People in Hong Kong are very generous with their money but [don’t] organize it well,” Chen adds. “They aren’t very deliberate in thinking about the impact or difference they have made with their philanthropy. It is more driven by emotion or business and not real philanthropy or meaningful engagement.”

Darius Yuen

Darius YuenAnother philanthropist who is trying to change the giving culture is Darius Yuen, formerly a senior managing director at Bear Stearns. When the firm collapsed, Yuen saw an opportunity to reevaluate his life and decided that going to work in a worthy charitable cause was a good first step. Unsurprisingly, even flush with funds, he didn’t find what he wanted in a traditionally tight-lipped culture. “Part of me wants to solve social problems and try to figure out a solution to these social problems, whether it’s the environment, poverty alleviation, or education,” he says. “I believe that this world needs more solutions than just giving away money.”

Yuen travelled to Germany to attend the European Venture Philanthropy Association Forum and soon after founded the SOW Asia Foundation. The foundation has ploughed a mostly lonely furrow in Hong Kong, investing in commercial businesses that offer a high rate of social and/or environmental return. Grants have ranged from $50,000 to $250,000 to SOW Asia projects in Hong Kong, China, South and Southeast Asia, and Africa. From supplying low-voltage solar-powered computers to facilitating research into environmentally friendly building materials, Yuen has his hand in projects that would look perfectly at home in other venture philanthropy portfolios. In 2010, he was named one of 48 Heroes of Philanthropy in Asia by Forbes magazine.

But Yuen isn’t necessarily a hero in Hong Kong, where that kind of philanthropy is rare. “I don’t think people get the concept of venture philanthropy,” he says. “They are still confused as to which bucket to put their money in. They wonder, is it investment or is it philanthropy?”

Li Ka-Shing

By Sandra Salmans

Li describes his foundation as a "third son" and has pledged to donate a third of his assets to philanthropic projects in China and globally.

Li Ka Shing is known by many superlatives: the richest man in Asia (Forbes estimates assets of $31 billion), “superman” (for his business acumen), even (such is his celebrity) the only businessman to have a wax statue at Madame Tussauds in Hong Kong. But these days it is as a philanthropist that he truly stands out. Not only is Li, age 86, a leading donor (at least $1.65 billion from his foundation, to date, and more from his other sources), he is the outspoken exemplar of the kind of socially progressive giving which, although increasingly popular in the U.S., is rare in China, where wealth is traditionally kept within families and donors favor a low profile.

In fact, when he established his foundation in 1980, one of the three objectives he defined was to “nurture a culture of giving.” His two other goals are education reform and advances in medical research and services, and he’s made major contributions in both of those areas in Hong Kong (where he lives), China, the U.S., Singapore, and India, among other countries. In 1981 he founded Shantou University in Southeast China, with the intent of establishing it as a showplace for both higher educational reform and the life sciences, partly through a network of international partnerships and exchanges with some 20 colleges abroad. In the U.S., Stanford University’s medical school opened the Li Ka Shing Center for Learning and Knowledge in 2010, and in 2012 the University of California, Berkeley, opened the Li Ka Shing Center for Biomedical and Health Sciences. Closer to home, Li has sought to inspire a culture of giving through a campaign called “Love HK Your Way!” which encourages grass-roots projects designed to bring people together and improve the community.

As his website attests, Li’s dedication to philanthropy is the result of a difficult youth. In an unusually soulful note, the site declares that “trials, hardship, and a sense of loneliness accompanied him on his journey from a small coastal village in China to the flourishing enterprise he oversees today.” Born near Shantou in mainland China, Li fled to Hong Kong with his family during the Japanese occupation, then was forced to leave school at the age of 15 for a job in a plastics factory after his father died of tuberculosis. As bootstrap stories go, Li’s is unparalleled: He became the factory’s general manager by the age of 19, and by the age of 22 had started his own plastic manufacturing business. His empire today, under the umbrella of the Cheung Kong Group and Hutchison Whampoa, includes immense holdings in real estate, shipping, telecommunications and biotechnology, and makes up 15 percent of the market capitalization of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Li, whose two sons manage his businesses, has described his foundation as his “third son” and has pledged to donate one-third of his assets to support philanthropic projects. “To be able to contribute to society and to help those in need to build a better life, that is the ultimate meaning in life,” he has said. “I would gladly consider this to be my life’s work.”

Can Country Policies Drive Philanthropy? Yes, and they Should!

By Crystal Hayling

In what ways is public policy encouraging or discouraging the growth of strategic philanthropy?

Princeton University alums are well known as big spenders, or, more specifically, as big givers. Starting from freshman year—before they have reached alumni status—contributions are solicited and celebrated. In this way, the school grooms and encourages every philanthropic impulse. Princeton creates a culture where giving is the norm. Pride in supporting the institution reinforces the school’s ability to excel and flourish.

Is it possible for a country to be like Princeton?

In their much lauded book Nudge, University of Chicago and Harvard Law School authors Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein break down the way policies impact the behavior of individuals and groups. While remaining firm advocates of free will, Nudge shows the way the presentation of policy options can encourage positive behavior and discourage negative ones. When the book came out in 2009 foundation CEOs like myself spent a great deal of time discussing applications of its theories to increase immunization rates, encourage retirement savings, and create ease of exercising through refurbished parks and biking paths.

In kind, our behavior as philanthropists is as clearly shaped by philanthropic public policy. The United States is widely recognized as an exceedingly charitable country. And a large part of that charitable giving has been stimulated by a sophisticated blend of tax and nonprofit laws that encourage such behavior. No one can quantify the exact financial impact the nation’s generous tax policy has on giving, but there is rarely a question that it plays an important role.

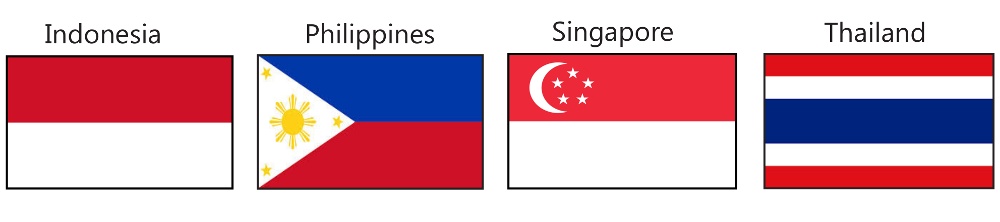

So when I moved to Singapore, a country where public policy wonks feel right at home, I became interested in digging deeper on this correlation between public policy and philanthropy to see if it held true here as well. The Lien Centre for Social Innovation, on whose board I sit, received funding from the Canadian International Development and Research Centre to conduct a study of philanthropic policy in four Southeast Asian economies—Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand—to better understand the issue. We set out to answer the question: in what way is public policy encouraging or discouraging the growth of strategic philanthropy in the region? As a part of the report, entitled “Levers of Change: Philanthropy in Select Southeast Asian Countries” and released in February of last year, we conducted in-depth interviews and surveyed focus groups with key stakeholders.

The study’s findings reveal consistent linkages between thoughtful public policy and increases in philanthropic giving, but also found many gaps in policy and practice that hinder philanthropic growth, particularly strategic philanthropy focused on addressing social problems.

This is not an academic question. The spectacular growth in wealth in Southeast Asia is matched only by the stark unevenness of its distribution. Many chroniclers of the super-rich seem to assume that philanthropy will automatically increase in tandem. But the charitable impulse on its own will never be sufficient to form the building blocks of a strong civil society necessary to address social inequity. The culture of philanthropy can be nurtured to become vibrant, strategic, and effective.

Though data is limited (indeed the lack of proper data was found to be an inhibiting factor to developing the philanthropic sector across all countries), Singapore clearly emerged as a leader in the region as a driver of increased giving through policies that encourage domestic contributions to voluntary organizations. Donors receive a 250% charitable deduction for contributions made to specific nonprofits. That policy has paved a consistently growing trend of cash contributions in the country.

The other three countries studied have had more mixed focus on philanthropic policy with less clear-cut outcomes as a result. None of the other countries offered such bold tax benefits for charitable giving, but the study showed why: the personal income tax is a weak policy tool in developing and emerging economies because the pool of income tax payers is relatively small, effective tax rates relatively low, and tax capture rates modest by most counts. Thus, the political challenge of providing tax breaks for the wealthy, a heated debate even in the US where it has been a policy for decades, is a non-starter in countries where tax breaks are unlikely to be significant enough to sway donor behavior.

Innovation in philanthropic policy and practice is correspondingly an imperative in the region if private wealth is to achieve its potential to catalyze systemic change and social improvement. In the Philippines, for example, a unique debt-for-nature loan forgiveness scheme created the Foundation for the Philippine Environment that supports biodiversity conservation and sustainable development.

In Indonesia, there are new approaches to zakat donations led by innovative nonprofit organizations that offer the emerging middle class in the largest Muslim nation options to support community development to combat poverty.

The symbiotic, yet sometimes uneasy, relationship between nonprofits and donors was highlighted as a challenge in all four countries. Nonprofits would prefer donors to offer longer-term support to build institutional capacity, while donors cite weak accountability as a reason many create their own projects rather than working with NGOs. Robust networks of donors and nonprofits, as evidenced in the Philippines and increasingly in Singapore, can begin to help overcome these challenges through knowledge sharing of best practices.

All four countries would benefit from concerted donor education to advance strategic philanthropy and move beyond checkbook charity. A promising sign is the nascent development of community foundations and giving circles where donors, large and small, can pool financial resources and match funds with expertise on community needs to support worthy NGOs. The enabling environment for strategic philanthropy can be improved through policies that encourage innovation in civil society, increase non-profit and philanthropic accountability, improve data collection, and celebrate risk-taking leaders.

Some argue that the culture of giving in Asia, which has been characterized as individually driven, family-clan oriented, and private or anonymous in nature, does not lend itself to being influenced by public policy. However, the evidence from this report suggests otherwise. The stage is set for new philanthropic leaders to come to the fore and public policy can go a long way to create the enabling environment for those strategic philanthropists to make a real impact.

Mark Zuckerberg/Priscilla Chan’s $45 Billion Dollar Charitable LLC

By Doug White

Making Philanthropic History

In December 2015, Priscilla Chan and her husband Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s co-founder and chief executive officer, made history — not because of their enormous wealth but because they pledged to use almost all of it to make the world a better place.

The couple pledged to give away 99 percent of Facebook’s stock, which, at the time of the announcement, was valued at approximately $45 billion, making it the largest pledge in the history of philanthropy.

When they made their stunning announcement, they were speaking primarily not to the media but to their newborn daughter Maxima.

In a letter that will undoubtedly rank among the most important that will ever be addressed to Maxima, her parents outlined their profound goals to improve health and education, and to decrease inequality. "Our society has an obligation,” Chan and Zuckerberg wrote, “to invest now to improve the lives of all those coming into this world, not just those already here. But right now, we don't always collectively direct our resources at the biggest opportunities and problems your generation will face."

They then acknowledged one of the more ignored basic truths of philanthropy: fundamental change requires time: “We must make long-term investments over 25, 50 or even 100 years. The greatest challenges require very long time horizons and cannot be solved by short-term thinking.”

Some people were quick to criticize the vehicle the couple is using to make their impact — a limited liability company instead of a traditional public charity or foundation. But the criticism is premature and shortsighted. Scholars and our better nonprofit leaders are coming to understand that new ideas about philanthropy are needed, that the world’s most difficult problems are going to need new approaches. While the traditional philanthropic model has resulted in remarkable social accomplishments, it is inadequate to addressing society’s most intractable and large-scale social problems. We need an addition, re-defined structure, and Chan and Zuckerberg may be doing exactly that.

Perhaps Zuckerberg comes to philanthropy naturally. First came the enormous wealth, even before Facebook went public. In 2010 he joined the Giving Pledge, a group of the world’s wealthiest people who have dedicated at least half of their fortune to philanthropy. (Currently there are 154 people who have committed to the pledge.) He was 29 when he joined, making him the youngest member at the time.

Despite what seems to be the gelling of his philanthropic thinking, Zuckerberg has had no roadmap. Our perception is still that those who give away vast sums of money do so in the context of years of worldly experience. Even Bill Gates, whose wealth also came relatively early on, worked longer to make his money and turn his attention to the broader needs of the world. Yet Zuckerberg and Chan are already consistently topping the lists of the world’s most generous philanthropists.

Still, it’s a learning process. In 2010, Zuckerberg devoted $100 million — his portion of a matching gift totaling $200 million — to help the failing schools in Newark, New Jersey. Dale Russakoff, who wrote “The Prize,” which details the gift and what turned out to be its disappointing impact, suggests that Zuckerberg learned that giving away money is a far more complex and humbling endeavor than he might have expected, a case study, Russakoff said, in the difficulty of translating good intentions into concrete results. Most of us tend to think $100 million can fix almost any problem. But in fact the scale of the problem in Newark dwarfed the size of the gift. In addition, the competing political and business priorities — to say nothing of the parents and children most affected (and, as it turns out, not much was said to them or on their behalf) — were overwhelming.

One key to understanding Zuckerberg, and perhaps it provides an insight to what drives his giving, might be that he can be described as a rebel, an anti-authoritarian. When he was still a high school student at Phillips Exeter Academy, he developed the Synapse Media Player, which would learn people’s music-listening habits. Although both Microsoft and AOL were interested in buying the program and in hiring him, he declined. College beckoned.

By the way, while Harvard was where Zuckerberg created Facebook, the story can actually be traced back to Exeter, which had something called The Photo Address Book so students could keep track of one another. Because the name doesn’t trip off the tongue with ease, for decades the students had been calling it “The Facebook.” In his senior year there, the school put the book online.

Another key, one that hints at an overarching thesis that brings together his business and philanthropic mindsets: Zuckerberg has said that what’s important in starting a company isn’t just to start a company but to “do something,” to go after problems and not do easy things, a philosophy that may have been the driver of his decision to go to college and rebuff offers from corporate America. “A lot of companies,” he once told students at Stanford University, “are operating on small problems.” The goal is to do something tangible. “The most interesting thing,” he said, “is to operate on something fundamental on how humans live. It was fundamental for me. I feel this need really acutely. I wanted this.”

He clearly wants a lot, and it looks like he has the intellect, passion and resources to make the world a better place.

We’re starting to see what that world will look like when the anti-authoritarian is the one in charge.

Cynthia Wu: Tough Love

By The Editors

After attending The Philanthropy Workshop in New York, Ms. Wu came home and was gifted her family company's foundation. How has she done with it?

“We were always doing volunteer work when we were growing up, and I wanted to learn more about the nonprofit landscape,” said Cynthia Wu, who was just 24 when she signed up for The Philanthropy Workshop. “But when I came back to Taiwan [from New York], I was given this foundation. I wanted to get a director, but my father said, ‘No, we’re not going to spend money on that. You’re going to be the director.’”

Wu’s family controls a sprawling Taiwanese conglomerate, Shin Kong Financial Holding, and the company’s Shin Kong Life Foundation has made about $54 million in grants over 22 years. But despite deep roots on the island, Wu said it was far from the kind strategic enterprise that she had had been taught to appreciate at TPW.

“This foundation was essentially just cutting checks,” she said. “The mission was simple: help the sick, the weak, the old – we were giving in a kind of scattershot way. If people were in trouble, they’d call us, and the P.R. department would cut a check. It’s been functioning, but not in the way that I was taught by Sal [LaSpada, the former director of The Philanthropy Workshop].”

Wu’s first decision was to abandon the customary reliance on company volunteers, and hire some staff. “People said, staff? What do you need staff for? The phone only rings twice a day!’,” she recalled with a laugh.

But the real fun started when she began to inspect the books. “It got kind of ugly,” she said. “I had to cut a lot of the funding. I went through the list of grants and found a lot of stuff that wasn’t in the mission statement at all – like, $300,000 for choir groups! They’d gotten money for pianos, for lessons, for everything. These were not people in need. These ladies had nothing to do. It was more of a social thing.

“And then I found out that the vice-chairman’s wife was the founder of this group. So you can imagine the toes I had to step on. He had 450 ladies complaining to him!”

Wu forged ahead. Concerned with women’s health (an often-taboo subject in Taiwan), she launched breast cancer awareness programs. Worried about the forgotten elderly, she began outreach and oral history projects. Alarmed by the poverty of Taiwan’s small indigenous population, she earmarked health care and education programs for them.

All along, she sought to bring Western, TPW-inspired strategic thinking to a foundation steeped in Chinese tradition – a big leap from cutting annual checks for the local four-wheel-drive club. “I think we can take a lot more risks,” she said. “It’s a privilege to do that. We’re not a government agency. We’re not restricted by the bureaucracy. We can do experiments, like a lab. That’s the vision that I have.”

But Wu’s vision remained contentious – “always under attack,” she recalled – and her father kept his own counsel. “He never said much,” Wu said. “For two years, he was just watching.” The moment of truth came at a recent board meeting, where Wu’s performance as director was to be evaluated. After she and her staff made a formal presentation, describing two years of activity, several company elders (including the embattled vice-chairman) decried her decisions. Wu, just 27, began to think that her days as the foundation’s director were over.

Then her father stood up. “My father actually spoke out on my behalf!” Wu said, her voice betraying both surprise and pride. “He said, ‘Times must change, and things can be done differently. Let us see a show of hands to see how we think Cynthia is doing.’” She was re-elected.

Shiv Nadar

By Sandra Salmans

The Indian billionaire is committed to rural youth in his native country. His plan? Grants for education.

No one deserves such reverence as one’s mother, says the Mahabharata, one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India. So Shiv Nadar listened closely to his own mother 20 years ago, shortly after his software company, HCL Group, established a partnership with Hewlett-Packard and he found himself in possession of a large sum of money. In Nadar’s telling, he wanted to “give back” to the country that had helped make him a billionaire, but he wasn’t sure the timing was right. “It’s like standing in front of the sea,” his mother told him. “If you wait for the waves to subside before you go out to swim,” nothing will ever happen.

With that, he plunged in, ultimately building one of India’s greatest philanthropies. Nadar, whose personal wealth is estimated at some $6.5 billion, has pledged a fifth of that sum for philanthropic work, and today the Shiv Nadar Foundation is a major force in using education to transform the lives of poor but deserving students who, like Nadar himself, come from rural India. Nadar, now 69, says that he chose to focus on education because he understands its power. He grew up in Tamil Nadu, in South India, where he attended local schools and earned his bachelor’s degree from a technology college. In 1976 he helped create HCL in one of Delhi’s barsatis—the small rooms that have been compared to the garages where many of Silicon Valley’s startups were born.

It was in 1994, shortly after that conversation with his mother, that Nadar launched his philanthropic effort with the SSN Trust, named after his late father. Its $30 million endowment is used mainly to fund SSN Institutions, a 250-acre campus in Tamil Nadu’s capital, Chennai, which today is one of the top private engineering and business schools in India. Starting in 2009, he set up two residential VidyaGyan schools in Uttar Pradesh (in North India, near Delhi) that provide free education and leadership training. The undertaking has been characterized as much more than a handout: It is a “radical social experiment” to address the deep social imbalances within India. This year some 80,000 students applied for the 1,300 slots between grades 6 and 12, and the foundation is currently scouting a location for a third school as well as beginning to set up K-12 Shiv Nadar Schools. In 2011, Nadar extended his efforts with the establishment of the interdisciplinary Shiv Nadar University, also in Uttar Pradesh.

These days, philanthropy runs in the family. Nadar’s wife Kiran has an art museum in Delhi. Daughter Roshni, who is Nadar’s designated heir to take over HCL when he retires, is deeply involved in overseeing the VidyaGyan schools and, as a representative of the Foundation, has also been involved in a joint initiative with the Rajiv Gandhi Foundation to promote the education of Dalit and Muslim girls in some of the most backward districts in Uttar Pradesh.

Shiv Nadar’s mother would be proud.

Ada Wong

By Ben Huang

The Good Lab, a Hong Kong initiative aimed at bringing together changemakers.

Google “Ada Wong” and the first several entries you’ll see are about a mysterious but wildly glamorous industrial spy in the international video game phenomenon, Resident Evil. It’s only towards the bottom of the list that you might encounter the real Ada Wong—a demurely dressed Chinese-born Hong Kong attorney who is a tireless promoter of education and the arts in Asia generally, and in Hong Kong in particular.

Wong, who earned a bachelor’s degree at Pomona College in California and qualified as a solicitor in London, returned to Hong Kong in the 1980s and joined the law firm of Philip K. H. Wong, Kennedy Y. H. Wong & Co. in 1986, where she is the partner in charge of the firm’s commercial and corporate finance department. That would seem to be time-consuming enough, but Wong has been a relentless force for good outside of her day job.

Over a 12-year period that straddled the former British colony’s 1997 reunification with China, Wong served as an elected member of its Urban Council and then the Wan Chai District Council, which she later chaired. These positions brought her in close contact with the local residents of one of Hong Kong’s oldest, busiest and most colorful districts—and, ultimately, a successful opponent of what she describes as the government’s “demolition strategy” in the name of urban renewal.

At that time, many people viewed Hong Kong as a transient city and a place primarily for making money. Instead, Wong asked, “What does it mean to be a Hong Kong person and what should we cherish besides money?” To provide local residents with a sense of identity and promote cultural pluralism, Wong and a group of like-minded friends established an advocacy platform for cultural policy, known as the Hong Kong Institute of Contemporary Culture (HKICC) in 1998. Under her leadership, the HKICC launched numerous projects to promote Hong Kong in the international arena as well as sponsoring local arts education; that includes Hong Kong’s first major international bilateral cultural festival—with Berlin in 2000—and the establishment in 2006 of its first (and only) school for the arts, media and design education, the Lee Shau Kee School of Creativity, for senior secondary school students. She is the supervisor at the school, whose students she refers to lovingly as “the children I do not have.”

Next Wong created MaD (Make a Difference) under the auspices of HKICC in 2010 to empower young people across Asia to think “creatively and innovatively,” she says, about personal, economic, social and environmental change. Last year MaD’s annual forum attracted over 1,600 young “MaDees” from across Asia. And in 2012 she launched the Good Lab, an initiative aimed at bringing together changemakers from all walks of life to work, collaborate and take action for a sustainable, innovative and equitable future.

In a city historically dominated by the twin juggernauts of banking and real estate, Wong is seeking to carve out a role for artists and others who think outside of the box. “Hong Kong deserves a better future,” she said in an interview. As for what drives her, Wong says, “You are not in this world just to make a living. You are here to make a difference, to bring hope and positive changes to society.”

The Community Foundation

By Sandra Salmans

How a hundred-year-old idea is reshaping philanthropy around the world.

Carnegie and Rockefeller had recently established—and lavishly endowed—their eponymous foundations when Frederick Goff, president of the Cleveland Trust Company, had a different idea: a “community trust” to which the city’s philanthropists could all contribute. Interest on the money, it was declared, would fund “such charitable purposes as will best make for the mental, moral, and physical improvement of the inhabitants of Cleveland.”

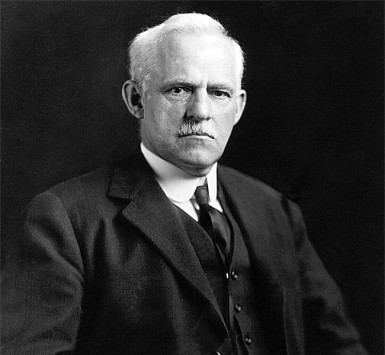

Frederick-Goff

Frederick-GoffThus, 100 years ago, was born the world’s first community foundation. (Bequests were, not coincidentally, deposited at the Cleveland Trust Company—setting a precedent for the charitable funds later established by financial services companies such as Fidelity, Schwab and Vanguard.) The Cleveland Foundation was soon leaving its mark on the city, supporting the creation of the so-called “emerald necklace” of the city’s parks, shaking up the corrupt judicial system, spearheading public school reforms that included equal education opportunities for girls. And within five years, community foundations (CFs) had sprung up in Chicago, Boston, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Buffalo, NY.

The growth of CFs since then has been immense, immeasurably greater than even the visionary Goff could have dreamed. Today there are an estimated 700 CFs in the US. According to CF Insights, a consultancy specializing in community foundations, assets at CFs in the U.S. totaled $66 billion in 2013, an increase of $8 billion over the previous year. The Silicon Valley Community Foundation (SVCF) led the way, at $4.7 billion, followed by the Tulsa Community Foundation, with $3.9 billion, and the New York Community Trust, with $2.4 billion. (SVCF’s assets, which ballooned with a $1 billion gift from Mark Zuckerberg in 2013, surged ahead again in 2014 with a $500 million stake in the camera maker GoPro from its founders.)

Mark Zuckerberg

Mark ZuckerbergIn 2013, commemorating the 100 years since the first CF was established, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation created a chair on community foundations at Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. And this past October, to celebrate the centenary of the CF, the Council on Foundations gathered leading philanthropic organizations in Cleveland, where it all began.

What’s more, the rest of the world—including the developing world—is rapidly following America’s lead. According to the latest tally by WINGS (Worldwide Initiatives for Grantmaker Support), a global network of grantmaker support organizations, and the Community Fund Atlas, which is underwritten by the Cleveland Foundation, there are currently some 1,100 CFs outside the US, in more than 50 countries and on six continents. Having launched in the US and Canada in 1914, the CF crossed the Atlantic to Britain about 35 years ago, took root in Germany around the time of reunification, spread to Russia and the former Soviet states, and is currently establishing a foothold throughout the developing world. Between 2010 and 2014, eight new CFs were established in Asia-Pacific, four in sub-Saharan Africa, four in Latin America and two in the Middle East. As the Mott Foundation aptly declared in its 2012 annual report, CFs are “rooted locally, growing globally.”

Whether in the industrialized world or the emerging one, CFs are identical in one key respect: They are public charities that tap the wealth of their communities, with the goal of redistributing it locally. That mission has universal application, asserts Emmett Carson, who is the SVCF’s chief executive officer and is also the visiting holder of the new Mott chair on community foundations. “We should think of the community foundation concept like water,” he says. “The water is the same, but it takes on the shape of whatever community you pour it into.”

Emmett Carson

Emmett CarsonAnd the fact is that CFs differ markedly from one country to another—and, increasingly, even within a country. In the developed world, many CFs are taking on a more activist role than in the past, initiating projects and partnerships as well as donating to established programs. What’s more, many are traveling far beyond their borders, accepting funds from a wider audience and playing a role on the national and even international stage

Meanwhile, the CFs that are springing up in less developed areas—Africa, Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe—are digging deep into their communities to convince residents to trust the very concept of pooling and distributing funds. While endowments and professional leadership are the hallmarks of long-standing CFs in the US, money necessarily takes a back seat to other priorities among CFs in emerging countries, where there are only small pockets of wealth. “They have to prove they’re relevant to the community and need to establish trust where often there are low levels of trust,” notes Nick Deychakiwsky, program officer for the Mott Foundation’s civil society team. In fact, in many cases those CFs have received a jumpstart by foundations such as Mott, Ford, Open Society and Aga Khan, and also appeal to the diaspora for funds.

Nick Deychakiwsky

Nick DeychakiwskyAs Jenny Hodgson, director of the South Africa-based Global Fund for Community Foundations, observes, community philanthropy is as old as, well, communities themselves. “Every country and culture has its traditions of giving and mutual support between family, friends and neighbors,” she has written, pointing to the tradition of burial societies across Africa and hometown associations in Mexico.

However, the new generation of community philanthropy institutions—fueled by factors ranging from a growing concentration of wealth to the popularity of social media, according to WINGS executive director Helena Monteiro—take a more strategic approach to giving. “Most are about development rather than donor services, and they do a lot of capacity building,” Hodgson told Giving. “They’re building civil society, essentially.” As the Kenya Community Development Foundation, a CF established in 1997, asserts on its website, its goal is “the growth and sustainability of communities by their strong engagement in owning and driving their development efforts.” (Italics are KCDF’s.)

Helena Monteiro

Helena MonteiroA sampling of this new breed of CFs offers a glimpse of the variety of programs being undertaken:

- In Egypt, the Community Foundation for South Sinai is working to support the Bedouin, who have long been marginalized. The CF is working on several fronts to raise the tribes out of poverty and preserve their heritage; projects have included teaching the women how to make useful wool products, and providing a camel to a boy who was his family’s breadwinner.

- In Costa Rica, the Monteverde Community Fund, initially founded to invest tourism revenue in preserving the rain forests, has added a social portfolio. Among other projects, it is promoting a community Internet-based radio station, training local youth to create programming and encouraging them to engage in public discourse.

- In Romania, multiple CFs have organized annual “swimathons” to raise their profiles, garner funds and spread the ethos of sharing. In Cluj, the country’s second most populous city, revenue went to support new programs for young people, including a robotics class in an elementary school and education for students with special needs.

- On the West Bank, the Dalia Association, a Palestinian CF, gave women from nearby villages $6,000 to build a park. The women went on to secure additional donations, including the land, utility hookups, a basketball court, a playground and a library.

- In Slovakia, the Banska Bystrica City Foundation—Eastern Europe’s oldest CF, initially launched as a World Health Organization project—has assembled a group of local donors that assist the city’s street children, provide support for the local Roma community, and encourage younger people to take an interest in philanthropy.

While all these CFs have struggled to raise money, elsewhere they have also encountered tight governmental controls or opposition. Even there, however, they are making headway. According to a recent report by CAF (Charities Aid Foundation) Russia, a support group for charitable and nonprofit groups, nearly two-thirds of the membership of CF governing boards comes from the authorities and business; even so, starting with one CF in 1998, Russia today has more than 45 community foundations. The situation is more problematic in China, where very few private organizations are permitted to do fundraising, grantmaking is relatively unknown and civil society is weak. Still, says Hodgson, “everybody is talking about community foundations in China. There’s lots of energy right now.”

That’s also an apt description of the situation in the US, where the biggest CFs are stepping up their game. Rather than limiting themselves to making grants to established programs, “community foundations are increasingly moving into the sphere of brokers for community solutions,” declares Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker, who heads the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo in New York State. Dedecker’s group was the prime mover in launching Say Yes to Education, an initiative that has brought together school parents, union leaders, the business sector and other stakeholders to provide year-round support to students K-12, including college scholarships.

Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker

Clotilde Perez-Bode DedeckerArguably the most striking example of the supercharged CF is the Silicon Valley Community Foundation. The result of a merger of two leading CFs in 2006, SVCF is not only the largest single grantmaker to Bay Area nonprofits, it’s the fifteenth largest international grantmaker in the United States, according to Carson. Furthermore, while SVCF draws much of its wealth from the affluent high-tech community, it also has donors who neither live in the Bay Area nor give to it, but choose to use SVCF as the means to distribute their philanthropy.

To Carson and others, these developments represent a natural progression for CFs in a society that is ever more global. “People increasingly see themselves as national citizens and, more likely, as global citizens,” he notes.” And because many Americans, or at least their parents, hail from different countries, they want to be able to send money overseas as well as to contribute to their new homelands. To compete in this arena—and also to counter the inroads made by financial services companies such as Vanguard and Fidelity, which are vying for donor-advised funds—the leading community foundations are carving out a niche in international philanthropy.

To some people in the CF world, venturing so far afield seems incompatible with the very notion of a community foundation. “A part of me says, ‘Shouldn’t it all be local?’” says the Mott’s Nick Deychakiwsky. But as someone with his own strong spiritual ties to Ukraine, Deychakiwsky concedes that “we’re all living in a more globalized world.” Ultimately, he hopes, globalization will lead to US-based CFs becoming more involved with community foundations abroad—relationships that could benefit organizations in both the developed and developing world. (And there are surprising similarities: Experts notes that CFs in emerging countries have a lot in common with those in rural areas of the US such as the deep South, where “hyperlocal” community development remains the sole focus.) “It’s amazing how much is transferable,” agrees Dedecker of the Community Foundation of Greater Buffalo, who is exploring the sharing of best practices with a CF in Nottingham, England. “The universal drive is for significant change and a strong sense of place,” she concludes. “That’s what unites us all.”

Lady Natasha Ri Isaacs & Lavinia Brennan

By Luke Norman

In a crusade to raise awareness of human trafficking, Lady Natasha and Lavinia Brennan found the power of the celebrity-crazed press to be their greatest weapon.

“We won a United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking (UN-GIFT) award before we’d even sold our first dress!” That's a boast delivered with delightful innocence by Lady Natasha Rufus Isaacs, co-founder of Beulah, a small London-based fashion label that continues to land outsized punches in its fight to combat the horrors of human trafficking.

Beulah’s story is more than a little infectious. Its journey—perhaps more fairly described as a sprint—from idea to global recognition epitomises a type of philanthropy impressive in its immediacy and impact. Beulah had yet to make its first sale when the company received a formal nod of approval from the United Nations in January of 2010. Despite the startup’s lack of employees and being run from a parent’s basement, Beulah was news.

The label launched with the consciously one-dimensional public purpose of raising awareness of modern slavery. Largely thanks to the duo’s network, Beulah was able to almost instantly deliver their message through enviable channels.

Quickly, with star customers from Sarah Jessica Parker to Kate Moss (via Pippa Middleton), famous bodies were snapped in its clothes. And alongside each mention of the shade of silk that Demi Moore sported was often a reference to the company itself. With the attention of febrile, fashion-obsessed teenage girls as well as seasoned Hollywood fashionistas, the outrage of human trafficking hit fertile, new minds. The company boasts more than 600 pieces of individual coverage in publications like Vogue, Harpers, and Cosmopolitan. In kind, their butterfly-logoed brand has built a life of its own.

Surprisingly few people are aware of the prevalence of modern slavery. In 2010 the UN reported that human trafficking represents a $32 billion-a-year industry in more than 130 countries. Beulah’s founders were as ignorant as everyone else until a months long visit to the Atulya slum in Delhi, where they volunteered at an aftercare center for female victims of the sex trade. Appalled by the realities they’d never considered, the pair resolved to shed light on the widely ignored practice.

“People seem to love the story behind the brand,” Rufus Isaacs says. The potency of their message has captured their clientele, and their own social circle, which includes both Prince William and Prince Harry, has similarly dazzled the tabloid press. With the added nuance of their shared Christian faith, the brand has been ripe for widespread publicity. Perhaps most importantly in the long run, Beulah’s product quality may be its quietest source of pride. This latter fact is a further credit to both women, both of whom share a lack of professional fashion experience.

“We’ve been very lucky,” Rufus Isaacs admits. The Beulah founders have cleverly leveraged the press attention that they hadn’t expected. When Kate Middleton chose to wear a Beulah design on her first official tour of South East Asia with Prince William, recognition of the label soared.

As is the case in much social entrepreneurship, Beulah has implicitly traded commercial viability for a tangible impact. (In the four years since its inception Beulah has yet to turn a profit.) And, for once, Britain's tabloid press is performing a public service.

When West Meets East

By Wangsheng Li

The President of Hong Kong’s ZeShan Foundation speaks out.

When I heard Asia being described by Western observers as “philanthropy’s new frontier,” I cringed.

I couldn’t help but wonder how easy it was for otherwise intelligent and well-meaning commentators to overlook the long-standing tradition of charitable giving in Asian societies. Is it mere ignorance or a backward missionary mindset at work? A lack of cultural sensitivity? This calls to mind the lukewarm reception that the push for the Giving Pledge initiative received in Asia.

The conventional thinking is that organized philanthropy (as opposed to charitable deeds that respond to specific situations, without a formal structure) is an invention of Western civilization. Historians and academics may have fun debating that. However, that view has had a profound influence on both Euro-American philanthropy professionals and their counterparts in the rest of the world when it comes to the advancement of philanthropy.

Zeshan Foundation Logo

Zeshan Foundation Logo

As an Asian who was educated in the West and honed his philanthropic skills in the US, I draw a distinction between localization and indigenization in the context of advancement of philanthropy. The former places emphasis squarely on developing locale-specific knowledge to promote leadership and professional pipelines for the local philanthropic sector; the latter aspires to transplant well-established theories and practices to a setting that is foreign, be it geographically or culturally.

That is not to dismiss or undervalue the enormous body of knowledge and skills our Western counterparts have developed and perfected over the years. On the contrary, they have priceless instructive value that can inspire and provoke.

In the past half-century or so, we have witnessed a remarkable transition of missionary-driven charitable endeavors in the post-colonial era to mandate-guided institutionalized philanthropy. If charity is a natural product of human civilization, the practice of institutionalized philanthropy is an inevitable result of a (maturing) civil society. Philanthropy with “Asian characteristics” is playing an important transformational role in social development and political reform. While our Western counterparts relish “strategic philanthropy,” I’m chewing on “catalytic philanthropy.”