About

Global Team

Roberta d’Eustachio

Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Roberta d'Eustachio (Rd'E) is an entrepreneur obsessed with delivering media from the social investor/philanthropist's point of view. That desire led to founding The American Benefactor, the first consumer magazine for philanthropists, as well as Giving Magazine and each of its subsequent evolutions: from print, to digital, to mobile with Facebook Instant Articles, delivering stories of social impact - for everyone, everywhere.

Rd'E has consulted with, and/or received investment from, leading global brands, including: The Economist, the Financial Times, Euro Money/Institutional Investor, the Pitcairn Family Office, Fidelity Capital and the World Bank as well as philanthropists and social enterprises around the world.

After serving as chief-of-staff to Dame Stephanie Shirley, the British Government’s Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy, Rd'E founded the AmbassadorsForPhilanthropy.com enterprise to give social investors a voice worldwide.

Dame Stephanie Shirley

Philanthropist & Believer-in-chief

Dame Stephanie “Steve” Shirley is a British entrepreneur turned philanthropist. She originally arrived in London as an unaccompanied Kindertransport child refugee from Austria during WWII. “Steve” was an early pioneer in technology and, after taking her company public, she has given more than $100 million to organizations that specialize in autism research and technology, including founding the Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University. Appointed by Prime Minister Gordon Brown to the title of the British Government's Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy 2009-2010, she believes in the advancement of the philanthropist voice worldwide.

Her memoir “Let It Go” was recently published, chronicling her life so far.

"Steve" is the Believer-in-chief to Giving Magazine, providing the means to imagine and execute its potential to the fullest.

Jerry Alten

Chief Curator

Jerry Alten is a world-renowned art director of magazines, across all devices, and other marketing and advertising work, winning many prizes in the media field. Under Walter Annenberg’s ownership of TV Guide, Jerry took the circulation from 5 million up to 19 million during his tenure as art director. He continued to work with Rupert Murdoch’s organization after the buy out of TV Guide and created the first interactive website for the magazine. Jerry was also the original investor in The American Benefactor Magazine and art director, which succeeded in obtaining more than $7 million worth of investment from Fidelity Investment's venture firm.

Brian Lipscomb

Chief Technologist

Brian Lipscomb has been involved with technology for over twenty years, and founded technology services company Divergex, based in Philadelphia. Specializing in all aspects of computers, Brian brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to Giving Magazine. His philosophy is: “Do it right, or don’t do it at all.”

Lipscomb adds: “Technology is a constantly evolving industry. People who use technology daily don’t have the time to study and learn all of the new and different terms and capabilities. I work to show people how technology can improve their efficiency, productivity and, ultimately, their lives.”

Jay Balfour

Managing Editor

Before Jay became the Managing Editor for Giving, he was a freelance writer and editor based in Philadelphia. With an academic background in Philosophy he leverages an informed perspective on everything from African music to youth movements in the West for several publications both online and in print. At Giving Magazine he shares a passion for unabated reporting and the ushering in of a new age in philanthropy.

Sandra Salmans

Executive Editor

Sandra Salmans is a New york-based writer and editor who works primarily in the nonprofit field. She began her career as a business and financial journalist at Newsweek and The New York Times, but has also covered national news, education and the arts. Prior to going freelance, she was a senior officer in communications for a leading foundation in Philadelphia.

Nicole Raeder

Digital Design Manager

Nicole delights in great design. That's why her commitment is compulsive; contagious even, to get it right. Or, change it. Or, change it again. Whatever is required to finding the way to the end point, which is sometimes the beginning. In other words, she never gives up, or stops, till the thing clicks.

She also loves cats.

Damon d'Eustachio

Co-Director, Global Membership

A foodie who navigated his way from the city of brotherly love to Charleston, S.C, Damon is devoted to serving nonprofits worldwide that believe the philanthropist voice must be heard.

Damon graduated from the College of Charleston in Art Administration and performed an internship at London’s prestigious Tate Gallery’s New York City office.

Jessica Lambrakos

Co-Director, Global Membership

Jessica is responsible for the management and development of the Global Awards for nonprofits of Giving Magazine for their nominated philanthropists and supporters.

She also serves as founder and executive director of her own nonprofit, “The Naked Truth AIDS Project”, which raises funds for AIDS prevention education programs in the USA as well as Africa.

Nick Cater

Contributing Editor

Nick Cater is a UK-based international writer and editor. A former Fleet Street journalist, he has reported from more than 40 countries so far on stories as diverse as war in Africa, environmental risks in Latin America, disasters in Europe, and the Asian sport of elephant polo.

Luke Norman

Senior Editor

Luke Norman is an experienced journalist and corporate social responsibility consultant. Having started at The Daily Telegraph, Luke has worked for a wide range of international media outlets before moving into the heady world of multi-national corporations and their sustainability commitments. Luke has transplanted himself and his family from London to Rio de Janeiro, where the views he now observes are deliriously engaging.

Doug White

Senior Editor

Doug White, a long-time leader in the nation's philanthropic community, is an author, professor, and an advisor to nonprofit organizations and philanthropists. He is the director of Columbia University's Master of Science in Fundraising Management program. He also teaches board governance, ethics and fundraising. His most recent book, “Abusing Donor Intent,” chronicles the historic lawsuit brought against Princeton University by the children of Charles and Marie Robertson, the couple who donated $35 million in 1961 to endow the graduate program at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Kent Allen

Journalist

Kent Allen is a longtime daily journalist and freelance writer. Over the past 20 years, while also writing about philanthropy and nonprofits, he has worked as an editor at The Washington Post, U.S. News & World Report and Congressional Quarterly. At present, Kent is a journalism and history teacher at The Field School, a middle and high school in Washington, D.C.

Lucy Bernholz

Journalist

Lucy Bernholz is a blogger and self-proclaimed “philanthropy wonk”. Her blog, Philanthropy 2173: The future of good, has been named a “best blog” by Fast Company and a “philanthropy game changer” by the Huffington Post.

Kim Breslin

Actor

Kim Breslin is an actress, comedienne, director, producer, artist, and chef. She has been an educator in North Philadelphia for 17 Years. Mother of two incredible children, she lives with her highly supportive cat, The Amazing Sid.

Cheryl Chapman

Journalist

Cheryl Chapman actively promotes philanthropy in the UK and globally via her journalism. She was the editor of Philanthopy UK: Inspiring Giving and now heads City Philanthropy, London, as its Director.

Stephen Dunn

Poet

Stephen Dunn, Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, is the author of 11 collections of poems, including “Different Hours,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 2001.

Regan Good

Poet

Regan Good is a freelance writer and poet living in Brooklyn, New York. She has written for The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times Magazine and others. She is currently at work on a memoir about growing up in a family of writers.

Sharilyn Hale

Journalist

Sharilyn Hale, M.A., CFRE is Founder and Principal of Watermark Philanthropic Advising where she offers strategies for meaningful giving, receiving and leading. A practitioner, author and educator, she brings a global perspective on philanthropy having served the nonprofit sector across North America, Bermuda and the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. She holds a graduate degree in Philanthropy & Development and is past Chair of CFRE International, the global certification for professional fundraisers setting standards for ethical and accountable practices.

Crystal Hayling

Journalist

Believer in a better world. Uppity advocate for social change. Former philanthrapoid. Crystal lives in Singapore where she helps donors develop strategy for effective grantmaking. She serves on numerous boards, and is a speaker and writer on civil society. Twitter: chayling

Holly Howe

Journalist

Holly Howe is a strategic communications consultant with a particular focus on the arts. She works as a freelance journalist, writing for various publications including FAD, RWD, House (published by the Soho House group) and the Irish Examiner. She also runs the Culture Vultures, a networking group for people in media and the arts. She can be found tweeting at @ hollytorious and in her occasional spare moments, she posts on her blog www.postcardsfromholly.blogspot.com

Wangsheng Li

Journalist

Wangsheng Li is president of ZeShan Foundation (Hong Kong) and a Senior Fellow of the Synergos Institute (New York City).

Lisa Macdonald

Journalist

Lisa MacDonald is a freelance writer and editor based in Toronto. A passion for philanthropy drives her involvement in initiatives that bring information and innovative ideas to Canada’s nonprofit sector leaders. Tweet her at @lisalmacdonald.

Andrew MacLarty

Actor

Andrew MacLarty is a New York based actor who has appeared on Boardwalk Empire and White Collar. Non-profit work includes narration for Partnership for a Drug-Free America, performances at the United Nations for Hurricane Katrina relief benefit shows, and Barefoot Theater Company’s ROCKAWAY benefit for Hurricane Sandy victims.

Bruce Makous

Journalist

Bruce Makous, ChFC, CAP, CFRE, has been a professional fundraiser for over twenty-seven years, with leadership positions in major educational, healthcare, and arts organizations. In 2009, he was named by the Nonprofit Times one of the “Most Influential and Effective” fundraisers in the US.

Peter D. Michael

Actor

For over 20 years, Peter D. Michael has been an established actor, voiceover talent and stand-up comedian. He is also an Emmy award winner.

Suzanne Reisman

Journalist

Suzanne is a U.S. international private client lawyer based in London. Suzanne assists philanthropists, their foundations, and international charities with cross-border philanthropy.

Julie Shafer

Journalist

Founder of Julie Shafer Development + Philanthropy, a national philanthropy consulting firm. Ms. Shafer offers a multifaceted skill set honed throughout 20 years as a philanthropy executive bringing a translational approach that bridges the gaps between philanthropists and non-profits.

Jade Shames

Playwright

Jade Shames is an award-winning writer living in Brooklyn, NY. His work can be found in The Best American Poetry blog, The LA Weekly, HOW art and literary journal, and more. He was awarded a creative writing scholarship to attend The New School where he received his MFA.

Amy Singer

Journalist

Amy Singer teaches Ottoman and Turkish history, as well as courses on Islamic philanthropy and the history of charity in the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University. Her recent publications include the book "Charity in Islamic Societies", and in 2008 she was awarded the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Award.

Sharit Tarabay

Artist

Sharit Tarabay painted the portrait of Gerry Lenfest. He is a painter and illustrator living in Montreal. He has his works published in magazines and books around the world.

James V. Toscano

Journalist

Jim Toscano is a principal in the consulting firm, Toscano Advisors, LLC, and an adjunct professor at the School of Business, Hamline University. Recently retired as president of the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, the cardiovascular research and education center of Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, he is a past chair of the Minnesota Charities Review Council and board member of Minnesota Council of Nonprofits.

Susan Yu

Journalist

Susan Yu is a journalist from the San Francisco Bay Area. She is an award-winning news reporter who was formerly based in Hong Kong for 14 years covering stories in Asia for international news media organisations. She is currently based in the United Kingdom where she freelances as a writer, editor and documentary film producer.

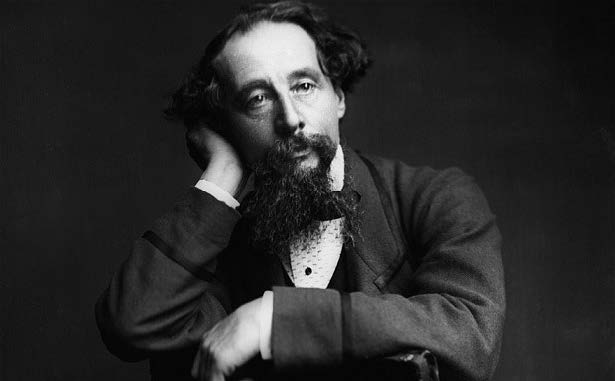

Bleak House

By Sandra Salmans

For Dickens, charity begins at home.

Should charity begin at home?

Yes, in the strong opinion of Charles Dickens, who used Mrs. Jellyby in Bleak House to blast what he termed “telescopic philanthropy.”

When we meet Mrs. Jellyby, she is busily engaged in dictating letters to her ink-stained wretch of a daughter on behalf of a project to settle some two hundred impoverished British families in Borrioboola-Gha, on the left bank of the Niger, where they are to cultivate coffee and educate the natives. Mrs. Jellyby’s home is squalid: Dinner is nearly raw and four envelopes float in the gravy, her innumerable children are virtually abandoned, and she herself is a mess—her hair needs brushing and her dress gapes in the back, revealing a lattice-work of stays “like a summer house.” But Mrs. Jellyby is blithely oblivious to the misery around her, the narrator writes; her handsome eyes “had a curious habit of seeming to look a long way off, as if . . . they could see nothing nearer than Africa.” When her oppressed daughter escapes her clutches to marry, the long-suffering Mr. Jellyby sends the girl off with one piece of advice: “Never have a mission.”

Like many of Dickens’ greatest characters—think Scrooge or Mr. Micawber or Miss Havisham—Mrs. Jellyby is regularly invoked by modern writers as a cautionary figure. Google “Mrs. Jellyby,” and you’ll see references on issues ranging from Gaza to coal mining. George Will accuses Arne Duncan, President Obama’s Secretary of Education, of a Jellyby-like indifference to the education of low-income children “within sight of his office” on Capitol Hill while pursuing loftier goals. Another writer, in a piece in Salon titled “Mrs. Jellyby Goes to Washington,” grumbles that the administration should focus on jobs, not global warming. A Christian scholar, arguing that Mrs. Jellyby and her like are motivated by anger, recalls an activist who nearly starved the office cat because he was morally opposed to the domestication of animals.

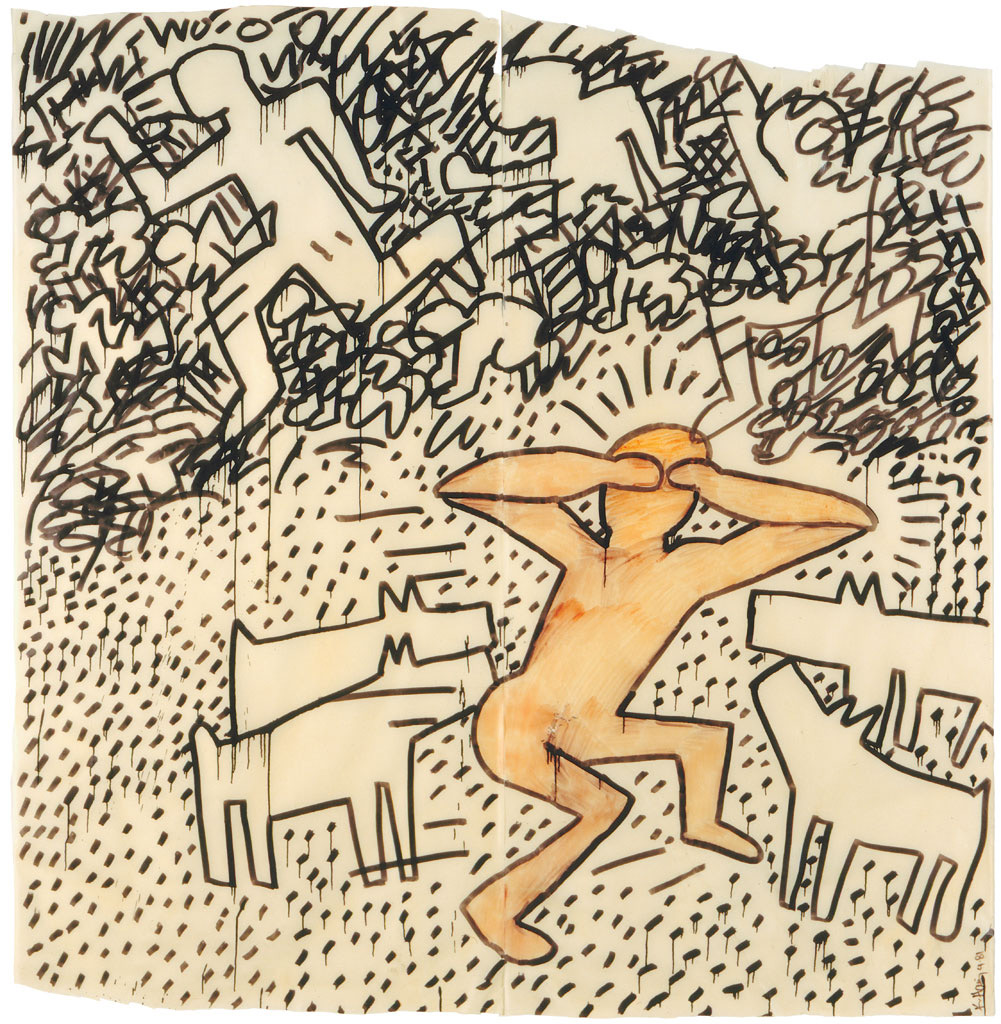

Mrs. Jellyby, drawn by Bill Cawley.

Mrs. Jellyby, drawn by Bill Cawley.But can we really learn from Mrs. Jellyby? Let’s remember that Dickens subscribed to the Victorian view that a woman’s place was in the home and was quick to condemn any woman who failed to be the “angel of the house.” (Never mind that Dickens himself was a less than exemplary husband and father.) It’s no accident that, at the end of Bleak House, Mrs. Jellyby, having discovered that her African king wanted to sell everybody— “who survived the climate”—for rum, takes up as her next cause the rights of women to sit in Parliament, a “mission” that Dickens evidently found as preposterous as Borrioboola.

While few charities are as ill-chosen as Mrs. Jellyby’s, philanthropy inevitably involves tradeoffs. Spending vast sums to fight AIDS in Africa can mean fewer funds for needy families closer to home; efforts to improve the conditions of the homeless here can result in less money for pre-school. Dollars, like time and energy, are finite. In the end, for philanthropists, the issue is arguably not how remote the cause but how deserving.

Giving 2.0

By Sharilyn Hale

Whether you give time, money, or expertise, the author outlines how individuals can be most effective with their gifts.

“Giving away money is easy—doing so effectively is much harder,” declares Laura Arrillaga-Andreessen in her introduction to Giving 2.0. It’s a common realization for those in the industry, but can still be a hard-earned truth. In language that is sometimes a little flowery, Andreessen positions philanthropy as a powerful pathway to emotional, intellectual and spiritual fulfillment, and ultimately a tool of personal and communal transformation. The book has been endorsed by a who’s who of America’s leading philanthropic leaders, including Melinda Gates, but this not entirely grounded book will likely be irrelevant to savvy givers. And if you are looking for a prescriptive how-to manual, Giving 2.0 will almost certainly fall short.

Arrillaga-Andreessen has philanthropy in her DNA. Her father is noted real estate mogul and philanthropist John Arrillaga, Sr. and her husband is Silicon Valley pioneer and investor Marc Andreessen. Thus her book is written from a place of obvious privilege. Still, Arrillaga-Andreessen has credentials. She describes herself as a “pracademic,” a practitioner as much as a scholar of charitable giving. She is founder of an organization called SV2 (the Silicon Valley Social Venture Fund), president of the Marc and Laura Andreessen Foundation, founder and chair of the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, and a lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, where she teaches a course on strategic philanthropy.

Giving 2.0 takes a deeply personal, anecdotal, and reflective approach to philanthropy that evolves over time. It is part philanthropic memoir inspired by the example of her mother, part conversational guide, part academic reader. Arrillaga-Andreessen provides a fair contextualization of philanthropy in historical terms and includes more than a passing mention of social media, an issue close to her family and home. She offers extensive lists of thought-provoking questions, and encourages philanthropists to learn from their giving in order to inform future gift decisions and create greater impact. Her suggestion to begin a giving journal to explore and document one’s journey towards effective philanthropy may not resonate with or be practical for everyone, but her premise that giving effectively requires a high degree of personal engagement is solid.

To her credit, Arrillaga-Andreessen consistently acknowledges her standing and addresses the often unspoken and complicated role of ego in giving. She quickly identifies the need to respectfully navigate relationships with charitable and nonprofit leaders as expert teachers and collaborators. She admits to past giving experiences that missed the mark, lending the book an air of authenticity. And she articulates the importance of advocacy and social justice philanthropy, two areas that are frequently sidelined and misunderstood, yet where systemic transformation is often rooted.

The author says she wrote Giving 2.0 for “anyone who gives anything, in any amount to create a better world.” Aspirationally, this includes donors at all giving levels (whether $10 or $10 million), volunteers, and social change advocates. The inclusive acknowledgement of the whole range of players in philanthropy is refreshing, albeit a little superficial. At the same time, it contributes to a cumbersome lack of focus and depth that doesn’t reflect Arrillaga-Andreessen’s obvious expertise.

The book may be especially useful to those who are new to intentional philanthropy, are highly motivated and want a broad survey of the “oceans of possibility.” Arrillaga-Andreessen refers to navigating these oceans herself, but the book would have benefited from more sophisticated navigation tools. More explanatory chapter titles and greater use of headings and subheadings would have made it easier to reference. Charts, checklists, and worksheets might have helped bring shape to the valuable approach, considerations and questions she offers.

Patient readers will be rewarded, however. The writing style is informal and conversational, which helps make it an accessible read in spite of the dense content. Comprehensive “Making It Happen” summaries at the end of each chapter help round things out and avoid the need for pen-in-hand reading. Philanthropists with children will also find some wonderful examples and tools to nurture and practice generosity as a family.

In the end, Giving 2.0 doesn’t offer a plan or framework to make giving easy as much as it welcomes readers to the path with a description of the many options available and a bracing call for self-reflection and exploration. Add this book to your library, but don’t expect a tell-all.

The Generosity Network

By Bruce Makous

How fundraisers can turn "must-do" transactional giving into transformative philanthropy.

Directed to volunteer and professional fundraisers alike, The Generosity Network is written from the dual perspective of a philanthropist, Jeffrey Walker, and a professional fundraiser, Jennifer McCrea. While most of the content is built on familiar industry relationship-based fundraising approaches, the book does lead into some new territory in the process.

Walker and McCrea begin with a focus on the distinction between transactional giving—what we might think of as day-to-day, hands-off philanthropy—and more thoughtful “transformative giving” built on careful connections and common goals. From both sides of a donation, the first half of the book acts as a self-help manual for developing meaningful gifts.

The authors focus on transformative giving as a central theme throughout the book, encouraging readers to mobilize personal values into action. Within that framework, both McCrea and Walker emphasize the benefits of community-based philanthropy and the viability of successful group structures.

Using this core concept as a filter, the second half of the book falls in line with a more deliberate description of how each step of the major gift development process is affected in operational terms. Some of the methods discussed won’t necessarily work for all donor personality types, particularly those who are not community oriented, and some parts of the book boil down widely known and accepted best practices. Still, even those who navigate the treacherous territory of asking major donors for money professionally will find some sections fresh and original. In particular, a chapter titled “The Ask,” and another on donor cultivation, called “The Jeffersonian Dinner,” allow Walker and McCrea to spin their years of experience into adaptable advice.

Whether reading The Generosity Network for personal edification, to get up to speed as a volunteer new to solicitation, or for advancement of a professional career, readers can expect a mostly effective mix of standard practices and new, sophisticated approaches to raising funds.

Abusing Donor Intent

By Doug White

Successfully challenging Princeton's (mis)use of his parents' endowment, William Robertson stood up for donors and the terms of designated contributions.

“Look at what this project could accomplish for the country.”

The words were whispered, although not intentionally, as Bill Robertson's emotions emerged. The weight of some years — more likely, some decades, as he thought of it — was being lifted. He would finally be able to tell an immensely personal story that happened to be about the largest lawsuit in the history of philanthropy.

During a period of six and a half years, beginning in the summer of 2002, the actions of this man, whom most everyone would assume by his outward demeanor of gentleness and accommodation could do no harm, at first surprised, then irritated, then upset, then offended, then riled, and then, finally, exploded the sensitivities of those who work in the patrician atmosphere that permeates the charitable organization that is Princeton University.

From his perspective, his goal wasn't to inflict damage. But he did think it was high time Princeton stopped inflicting its damage.

He wanted the voices of his parents to be heard. They had spoken through their enormous charitable gift forty years earlier, and their altruism was intended to accomplish something. Charles and Marie Robertson actually wrote it all down on a piece of paper, a carefully drawn, legally binding document hovered over by several attorneys — the family’s as well as the university's — before it was declared satisfactory.

To the casual observer of Princeton's world-renowned Woodrow Wilson School, things seemed to be going swimmingly. But by 2002, Robertson, who sat on the board of the foundation his parents created, had put up with enough. “The whole idea had gotten so off course,” he says, “it was time to pull the plug.”

He wanted nothing less than to remove the original money and all of its earnings from Princeton’s control and go elsewhere with it, not to benefit himself or any other individual, but to use it at another, more deserving university, one that would adhere more faithfully to his parents’ wishes. So, with his brother and two sisters, he went to court. The genteel environment of the boardroom would be replaced by the much more daunting rough and tumble venue of the legal system.

The arguments, the animosity and the money were about a basic idea: assuring that the dream of two people would become a reality. Like tens of millions of other donors — some wealthier, many far less wealthy — they wanted to do good things for the world, and they committed a sizable portion of their fortune and intellectual capital to make that happen.

This is a story about their children, led by Bill Robertson, who were determined to ensure, at whatever cost, that their parents’ intentions would live in perpetuity. The good people at Princeton say they were ensuring the Robertson legacy, but they may never have suspected, when disagreement on that point arose, that the children would be as resolute as they were.

It was the largest one-time amount — $35 million — anyone had ever donated to benefit a university. Charles and Marie Robertson were specific about the way the money was to be used. It was intended to help Princeton's Woodrow Wilson School for Public Policy and International Affairs focus on sending its graduates into those areas of the federal government concerned with international relations. “But the university,” the son says, “was ignoring my parents’ intentions. ” Furthermore, he maintains, Princeton's administrators were “harming the country as well.”

That's not, as you might imagine, the way Princeton saw it — or sees it today. The people there say they not only assiduously honor the concept of donor intent for all its supporters, but that in this case they were particularly faithful to the donors’ intentions. “Princeton,” a top administrator once said, “ has always used the funds given by Marie Robertson solely for the purpose for which she made her $35 million gift in 1961.” The university contends that the Woodrow Wilson School has been and continues to be one of the best in the country for public administration and policy with an international orientation, and that it was unfairly disparaged.

By 2002, the corpus of the gift, even after annual expenditures were accounted for, had grown to almost $700 million, a sizable portion of Princeton's endowment. By the spring of 2008, the fund had grown to $850 million. In part because of the sheer amount of money and in part because of Princeton's prominence in American academia, the lawsuit, the longest and most debilitating litigation ever in the history of American philanthropy, was destined to draw scrutiny. Among nonprofit executives, board members, donors and students of philanthropy, it is the most discussed legal case relating to donor intent. As the lawsuit wended its way through the court, it was covered extensively in the media, not only in outlets that specialize in nonprofit news, but in the general-circulation media as well.

In addition to the sum of money at stake and the audacious, public challenge to a pillar of the most academically revered group of universities in the country, another, more important reason the world took note — and why all donors and all nonprofit organizations should never forget what happened — is that this dispute, at its heart, sharply raised the awareness of the need for trust and honor in the sector of our society that most demands and depends upon those qualities.

Princeton officials claim they fulfilled their obligations. The Robertson family claims Princeton made a mockery of them. No matter what the defendants might say, Robertson insists he wasn't the bad guy; he was just trying to protect the family's honor.

Miuccia Prada

By Holly Howe

From the runway to her eponymous foundation, the designer brings her intellectual bent to everything she touches.

With a fortune estimated at roughly $11 billion, Miuccia Prada, 65, isn’t the world’s wealthiest philanthropist, but she is arguably the best dressed. Having inherited a family haute couture manufacturer, which began in 1913 with a small leather goods store opened by her grandfather, she has grown the company into a fashion powerhouse, extending the Prada brand by expanding into men’s wear, less expensive women’s wear, shoes and fragrances, and opening some 250 Prada stores, according to Forbes. Along the way, Prada has become synonymous with understated, classic chic.

But Miuccia, who has a PhD in political science and is a onetime member of the Communist party—a so-called “aristocommunist” who demonstrated in Courreges rather than jeans—is not your average designer. With her husband Patrizio Bertelli, she has emerged as a modern-day Medici, taking a leading role in sponsoring and collecting avant-garde art. In 1993, the couple established PradaMilanoArte, opening a space in Milan for contemporary sculpture. Two years later they renamed their nonprofit Fondazione Prada and expanded its capacity to include more contemporary art, photography, film, design, and architecture. That same year they hired curator Germano Celant to work at the foundation. It was a provocative choice: Celant is famous for his ideological commitment to arte povera—literally “poor art,” revolutionary works that attack the corporate mentality through unconventional materials and style.

Fondazione Prada, Venice

Fondazione Prada, Venice

Over the next couple of decades, the Fondazione Prada gallery in Milan hosted some two dozen exhibits by established and emerging artists, commissioned new video work, published over 30 books on art and architecture, funded film festivals and international touring exhibitions, and underwrote projects changing the traditional face of Milan, such as the permanent lighting installation by Dan Flavin at the church of Santa Maria Annunciata. It funded the Fondazione Prada Chair for Aesthetics at the University of Vita-Salute San Raffaele in Milan, as well as philosophy conferences that underscore Prada’s intellectual bent. Not all Milanese have embraced her vision. “Culture is absolutely not seen as a priority,” she told The Art Newspaper in 2009. “We wanted to give a work by Charles Ray to the city of Milan, but ten years later they still haven’t found a square in which to put it.”

True to her interest in art and architecture, Prada hired Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas to design her edgy stores. She also commissioned Koolhaas’ firm to design the so-called Prada Transformer—a tetrahedron-shaped structure in Seoul that appears to shift shapes as cranes rotate the building—and a pop-up structure in Paris that served as museum, disco, and gallery space over the course of 24 hours. A more permanent home for art is Ca’ Corner della Regina, an historic Venetian palazzo the foundation took over in 2011 to hold international art exhibitions.

"Synchro System" by Carsten Höller"

"Synchro System" by Carsten Höller"

In 2015 Fondazione Prada will host events during the Milan Expo, an undertaking dedicated to food safety, security, and quality that will promote Italy as well as global issues. That may be a good fit for the designer. In 2011 Miuccia Prada told WWD that she “probably” would seriously consider a career in politics. “Politics have always been a little of my passion,” she said. “And now I [could] use my work as a tool to do things other than fashion.”

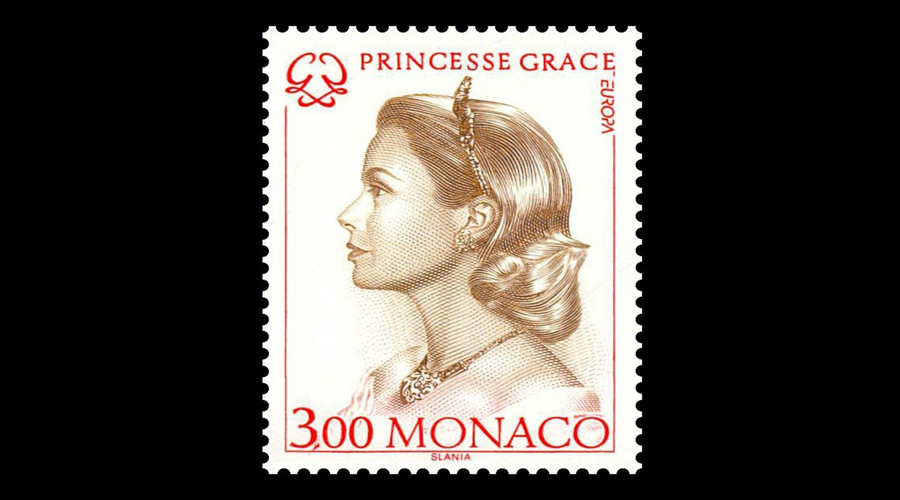

Princess Grace Foundation

By Bruce Makous

Originally created to salve Monaco's royal family's grief, the Princess Grace foundation celebrates three decades assisting emerging talent in theater, dance, and film.

She was the ultimate fairytale heroine, a radiantly beautiful commoner who’d caught the eye of and later married a prince. So when Princess Grace met an early death in a car crash in 1982, at the age of 52, it was fitting that her bereaved husband, Prince Rainier III, would create a foundation in her own country to foster and celebrate the arts.

The Princess Grace Foundation-USA focuses on the Princess’s primary philanthropic interests—discovering and assisting emerging artists in theatre, dance, and film. The foundation, a publicly supported not-for-profit headquartered in New York City, provides contributions to artists who are beginning their careers, primarily in the form of scholarships, fellowships and apprenticeships. To fund the foundation, the Prince mobilized Grace’s supporters, which included the likes of Frank Sinatra and Cary Grant. (The foundation is distinct from the Princess Grace of Monaco Foundation, which the princess created shortly after her marriage to encourage local artists and crafts people.)

Through its flagship program, the Princess Grace Awards, the Princess Grace Foundation-USA provides the financial assistance and moral encouragement needed by emerging artists so that they can focus on the creative process. Applicants must be nominated by nonprofit arts organizations, and a panel composed of distinguished professionals in theatre, dance, and film annually selects the winners on a competitive basis. Since the Foundation’s inception, more than 750 Princess Grace Awards totaling nearly $10 million have been given to performing artists. Many winners have subsequently achieved public recognition and critical acclaim, including Oscars, Tonys, Emmys, and other awards.

Among the notable winners are Robert Battle, the dancer and choreographer who now serves as Artistic Director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater; Yareli Arizmendi, the Mexican actress who played Rosaura in Like Water for Chocolate; Bridget Carpenter, playwright and screenwriter nominated three times for Best Dramatic Series by the Writers Guild of America for her work on Friday Night Lights; and Stephen McDannell Hillenburg, the animator, writer, producer, actor and director best known for creating the SpongeBob SquarePants TV series.

Those Princess Grace Award-winners who subsequently distinguish themselves in theater, dance, or film receive an additional form of recognition—the Princess Grace Statue Award. To date, 54 artists have received this award. A third type of recognition, the Prince Rainier III Award, established in 2005 after the Prince’s death, is presented to eminent artists who have also made significant humanitarian contributions. This award, which includes a grant to the philanthropic organization of the honoree’s choice, has been given to such stars as Julie Andrews, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Twyla Tharp, Denzel and Pauletta Washington, George Lucas, and Glenn Close.

Her family is carrying on her philanthropic legacy. Prince Albert II is the vice chairman of the foundation, and Princess Caroline is president of AMADE Mondiale, the Monaco-based NGO that Grace founded during her lifetime to help children in the developing world. Recently, for example, AMADE has provided support to Syrian children in refugee camps and to families devastated by the typhoon in the Philippines.

In fairytales, the royal couple lives happily ever after. But even when death intervenes, it seems, they can make others’ dreams come true.

Don & Mera Rubell

By Holly Howe

The Miami-based couple think of themselves as custodians with a grand purpose, sharing their 5,000-piece modern art collection with the world.

What to do when you have an art collection with over 5,000 pieces, including works by Keith Haring, Paul McCarthy and Jeff Koons? Share it with the world, according to Don and Mera Rubell, the Florida-based visual-art power couple. “You discover very quickly on this journey that you’re just the custodian of the important cultural artifacts of our time,” Mera once noted, in an interview with the Financial Times. “So how could you not make them available to the public?”

The Rubells never worked in the creative industries; Don, 74, is a retired gynecologist and Mera, 71, is former president of sportswear company Ellesse. But when they started dating, after meeting in the library of Brooklyn College in 1962, they discovered a shared passion for art and together explored artists’ studios and galleries in their free time. Initially there wasn’t much money to buy art—Don was in medical school and Mera worked as a teacher—but they allocated $25 a month from their $100-a-week income and set up the Rubell Family Collection shortly after they married in 1964. When Don’s brother, Studio 54 cofounder Steve Rubell, died in 1989, the Rubells inherited assets estimated to be worth $200 million. They sold those, freeing up cash to invest in hotel real estate and contemporary art.

Today, they have amassed what is widely regarded as one of the most important and edgiest private collections of contemporary art in the world. They are still collecting, an undertaking to which they devote about a quarter of their money. And, more than ever, it has become a family affair, particularly since their son Jason joined the board, and all three have to agree on a piece before they acquire it. (Their daughter Jennifer, an artist herself, opted out of the process to avoid any conflict of interest and to focus on her own career.)

In 1993, they took over a disused 45,000-square-foot facility in Miami where the Drug Enforcement Agency had housed confiscated goods, converted it into a 27-room museum and opened it to the public. The building displays some of their collection as well as their library of over 30,000 art tomes.

The Rubells see the museum as a way to educate people about contemporary art. “The major contribution of these private/public collections is it fills the gap for young people to see the art that’s being made today,” Don stated in an interview with the Art Economist. “I remember when our kids went to Duke and Harvard, and both of their art history courses ended with Andy Warhol... It’s a twenty-year lag. The young people never see what’s being produced that relates to their issues and passions.”

Staging exhibitions at most publicly-funded museums can be an arduous and time-consuming process, but the Rubell Family Collection has the agility to put a show together in a matter of months, and can display new acquisitions quickly. They also regularly loan items from their collection to other museums, and even transport entire exhibitions from their own museum to other institutions, such as the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington DC, and Fundación Banco Santander in Madrid.

But not everyone has welcomed the Rubells’ gifts. In the early 1980s, Don wanted to set up an art bequest with his alma mater, Cornell University, but the school’s art museum declined the gift, citing lack of space. A few years later, when Cornell reconsidered the offer and went back to the Rubells, administrators discovered it was no longer on the table. A shame, as they missed out on works by the likes of Jean–Michel Basquiat and Cindy Sherman.

Louise Blouin

By The Editors

An icon of the art world is leveraging culture and creativity against global challenges.

For a woman who has spent tens of millions of dollars of her personal fortune in pursuit of cultural development, Louise Blouin has generated some surprisingly negative press. Criticisms range from those who gently mock the Miss World-esque vision statements emanating from the French-Canadian to more serious accusations of unpaid debts and financial mismanagement at her media empire.

For the former at least, one can point to the peculiarly English (the Louise Blouin Foundation is based in West London) trait of finding unabashed, highly ambitious philanthropy hard to deal with. Add the vagueness that cultural philanthropic ventures can often carry and the alleged string of celebrity lovers (supposedly including Britain’s own Prince Andrew), and you can see why the British press have so enjoyed themselves with Mrs. Blouin. However, as publisher of more than 90 art titles per year, including the magazines Art + Auction, Modern Painters, and Culture + Travel, and as founder of the hugely influential ARTINFO.com, her place as a bastion of cultural influence has long been secure.

Blouin launched her $30 million eponymous foundation in 2005 with the vague intention of “supporting cultural development across the globe, disseminating culture beyond borders and generating new knowledge about creativity.” While some of its global aspirations may have been quietly scaled back, the Foundation’s London base has become one of the largest non-government, not-for-profit cultural spaces in the world.

Nearly a decade later, the Louise Blouin Foundation (LBF) has given space to a wide range of artists around the world while also hosting think tanks, workshops, debates, and summits on all manner of zeitgeists. Her annual Creative Leadership Summit in New York brings the challenge of using culture and creativity as catalysts for positive social change to the very highest table (past awardees at the grand event have included Bill Clinton and King Abdullah of Jordan) and LBF has boasted a 46-member advisory board including artist Damien Hirst, actor Jeremy Irons, and photographer Mario Testino.

Born and raised in Montreal, Blouin’s love affair with fine art started thanks to a volunteer posting at the city’s Museum of Fine Arts. Years later, Blouin even referenced her affinity for the arts in a split from her second husband and long-time business partner, John MacBain. The pair’s company, Trader Classified Media, was valued at almost $1 billion in the late 1990s. But, since 2000, Blouin has concentrated her resources on sharing the cultural message, both through her business, Louise Blouin Media, and through her foundation.

A Blouin quote on the LBF website neatly encapsulates both her philosophy and the reasons why some find it a little difficult not to ridicule her approach: “Verse three of Genesis: Let there be light. Yes, let. And then let us see it, learn from it, take it in and start to shine.”

Whatever you might think of such a statement, there is no denying the role that organisations like LBF can play. On its opening, Saumarez Smith, the British cultural historian, offered that the LBF could one day become as important as the Guggenheim Museum.

The LBF may not have scaled those heights (Blouin might well say “yet”) but given its proprietor there seems little doubt that its impact will continue to grow. “I don’t do this for power. I have everything I want in my life. I do this to make a difference,” Blouin said recently, with customary icy determination.

Great Castles, a One Act Play

By Jade Shames

Editorial Note: A fictionalized dialog of The Giving Pledge founders.

Warren Buffet, Melinda Gates, and Bill Gates sit in a living room. The room is lavishly decorated, but currently in a state of disarray. Empty wine glasses are peppered throughout the space as are half-eaten plates of hors d’oeurves. The party is over.

Melinda gets a notification on her Windows phone. Bill plays with his Microsoft Surface. They all nurse drinks.

Melina looks up from her phone.

MELINDA: Bettencourt is out. It’s official.

BILL: Oh well.

WARREN: A shame.

MELINDA: I’m a little surprised you guys aren’t more upset about this.

BILL: It’s one woman.

MELINDA: Exactly. One more down. How many billionaires are left in the world? The amount of signatories outside the US has been few and far between.

WARREN: The US is one of the most generous countries in the world.

MELINDA: Does that make any sense to either of you? France just elected one of its most socialist presidents in history. Hollande wants to give the rich a 75% income tax. Bill and Warren snicker.

WARREN: (Looking at Bill.) Oh brother.

MELINDA: So clearly they see the value in redistribution of wealth.

WARREN: Charity and socialism are two very different concepts.

MELINDA: Still, it seems a little backward that the French are so unwilling to give to charity after agreeing to such a high income tax! I mean first Arnaud Lagardère and now Bettencourt -

BILL: There’s a logical explanation.

MELINDA: Which is?

BILL: ...I was hoping you had it.

MELINDA: Seriously, is this a cultural issue? America is a young country - perhaps it’s growing up with a history of castles and kings. Louis XIV said that God wanted him to be king. He didn’t care about the people outside his castle.

WARREN: Après moi, le déluge.

MELINDA: Right. What did he care if people suffered? It wasn’t his place to give away his God-given right. And maybe there’s residual entitlement left over from centuries of King Louies.

BILL: I have a theory, and I really like your castle thing so I’m going to steal it...I think this is less of a cultural issue and more of a human issue. I think that adulthood is partially an illusion, and that everyone, no matter how old -

WARREN: (Laughing a little.) Melinda, why did he look at me when he said that?

BILL: We all like to play games. Some people feel that their wealth is the reward of the life game. You work hard and you build this great big castle of wealth. The child in them is saying “why would you give away your castle?”

WARREN: I’m reminded of Dennis Kozlowski’s $15,000 umbrella stand.

BILL: Yeah, see, it’s all about showing off. If you’re not a member of a world superpower, i.e. France, you might feel the need to show off a bit more.

MELINDA: I refuse to believe that all wealthy people can be so childish. Warren, do you believe this?

WARREN: I have a thought...but I don’t think either of you are going to enjoy it.

BILL: Please, go on...

WARREN: To reuse the idea of a castle...a castle is also a place designed to keep its inhabitants safe from the outside. I remember Jimmy Carter showing me pictures of children in sub-Saharan Africa wearing round black glasses. And I thought, “why are these children, who are clearly in poverty, shirtless, shoeless; how are they wearing glasses?” And the former President said, “they’re not glasses. They’re flies.” You see the children were never taught to wash their faces and so very small flies nest around their eyes. This eventually causes blindness. There are no words that capture that level of human suffering. But I remember hearing about these children and feeling, of all things, fear. Not for them, but for me. It’s not a rational fear. I know very well that I will never experience what these children experience, but to see it and accept it as real...well, it’s frightening. Kings built castles not just because they felt they deserved them or because they wanted to show off their grandeur...they built them to separate themselves from the rest of the earth. Remember Siddartha, the Herman Hesse novel. The Indian prince leaves his kingdom only to find the world is full of suffering and desire - and he welcomes this into himself. Once we accept that pain exists and it is happening all around us, are we not somehow responsible? Do we not welcome it in to our lives? I know it’s awful to say, but I wish...I wish I was never told what the glasses really were. There is silence for a moment.

MELINDA: If holding on to your wealth is like building a wall between you and the world, and, as you say, experiencing life differently - then what is philanthropy?

WARREN: I don’t know. Philanthropy involves a lot of faith. Maybe it, too, is about seeing the world for what you want it to be.

BILL: Or maybe it’s seeing the world for what it is.

Related Articles: