About

Global Team

Roberta d’Eustachio

Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Roberta d'Eustachio (Rd'E) is an entrepreneur obsessed with delivering media from the social investor/philanthropist's point of view. That desire led to founding The American Benefactor, the first consumer magazine for philanthropists, as well as Giving Magazine and each of its subsequent evolutions: from print, to digital, to mobile with Facebook Instant Articles, delivering stories of social impact - for everyone, everywhere.

Rd'E has consulted with, and/or received investment from, leading global brands, including: The Economist, the Financial Times, Euro Money/Institutional Investor, the Pitcairn Family Office, Fidelity Capital and the World Bank as well as philanthropists and social enterprises around the world.

After serving as chief-of-staff to Dame Stephanie Shirley, the British Government’s Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy, Rd'E founded the AmbassadorsForPhilanthropy.com enterprise to give social investors a voice worldwide.

Dame Stephanie Shirley

Philanthropist & Believer-in-chief

Dame Stephanie “Steve” Shirley is a British entrepreneur turned philanthropist. She originally arrived in London as an unaccompanied Kindertransport child refugee from Austria during WWII. “Steve” was an early pioneer in technology and, after taking her company public, she has given more than $100 million to organizations that specialize in autism research and technology, including founding the Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University. Appointed by Prime Minister Gordon Brown to the title of the British Government's Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy 2009-2010, she believes in the advancement of the philanthropist voice worldwide.

Her memoir “Let It Go” was recently published, chronicling her life so far.

"Steve" is the Believer-in-chief to Giving Magazine, providing the means to imagine and execute its potential to the fullest.

Jerry Alten

Chief Curator

Jerry Alten is a world-renowned art director of magazines, across all devices, and other marketing and advertising work, winning many prizes in the media field. Under Walter Annenberg’s ownership of TV Guide, Jerry took the circulation from 5 million up to 19 million during his tenure as art director. He continued to work with Rupert Murdoch’s organization after the buy out of TV Guide and created the first interactive website for the magazine. Jerry was also the original investor in The American Benefactor Magazine and art director, which succeeded in obtaining more than $7 million worth of investment from Fidelity Investment's venture firm.

Brian Lipscomb

Chief Technologist

Brian Lipscomb has been involved with technology for over twenty years, and founded technology services company Divergex, based in Philadelphia. Specializing in all aspects of computers, Brian brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to Giving Magazine. His philosophy is: “Do it right, or don’t do it at all.”

Lipscomb adds: “Technology is a constantly evolving industry. People who use technology daily don’t have the time to study and learn all of the new and different terms and capabilities. I work to show people how technology can improve their efficiency, productivity and, ultimately, their lives.”

Jay Balfour

Managing Editor

Before Jay became the Managing Editor for Giving, he was a freelance writer and editor based in Philadelphia. With an academic background in Philosophy he leverages an informed perspective on everything from African music to youth movements in the West for several publications both online and in print. At Giving Magazine he shares a passion for unabated reporting and the ushering in of a new age in philanthropy.

Sandra Salmans

Executive Editor

Sandra Salmans is a New york-based writer and editor who works primarily in the nonprofit field. She began her career as a business and financial journalist at Newsweek and The New York Times, but has also covered national news, education and the arts. Prior to going freelance, she was a senior officer in communications for a leading foundation in Philadelphia.

Nicole Raeder

Digital Design Manager

Nicole delights in great design. That's why her commitment is compulsive; contagious even, to get it right. Or, change it. Or, change it again. Whatever is required to finding the way to the end point, which is sometimes the beginning. In other words, she never gives up, or stops, till the thing clicks.

She also loves cats.

Damon d'Eustachio

Co-Director, Global Membership

A foodie who navigated his way from the city of brotherly love to Charleston, S.C, Damon is devoted to serving nonprofits worldwide that believe the philanthropist voice must be heard.

Damon graduated from the College of Charleston in Art Administration and performed an internship at London’s prestigious Tate Gallery’s New York City office.

Jessica Lambrakos

Co-Director, Global Membership

Jessica is responsible for the management and development of the Global Awards for nonprofits of Giving Magazine for their nominated philanthropists and supporters.

She also serves as founder and executive director of her own nonprofit, “The Naked Truth AIDS Project”, which raises funds for AIDS prevention education programs in the USA as well as Africa.

Nick Cater

Contributing Editor

Nick Cater is a UK-based international writer and editor. A former Fleet Street journalist, he has reported from more than 40 countries so far on stories as diverse as war in Africa, environmental risks in Latin America, disasters in Europe, and the Asian sport of elephant polo.

Luke Norman

Senior Editor

Luke Norman is an experienced journalist and corporate social responsibility consultant. Having started at The Daily Telegraph, Luke has worked for a wide range of international media outlets before moving into the heady world of multi-national corporations and their sustainability commitments. Luke has transplanted himself and his family from London to Rio de Janeiro, where the views he now observes are deliriously engaging.

Doug White

Senior Editor

Doug White, a long-time leader in the nation's philanthropic community, is an author, professor, and an advisor to nonprofit organizations and philanthropists. He is the director of Columbia University's Master of Science in Fundraising Management program. He also teaches board governance, ethics and fundraising. His most recent book, “Abusing Donor Intent,” chronicles the historic lawsuit brought against Princeton University by the children of Charles and Marie Robertson, the couple who donated $35 million in 1961 to endow the graduate program at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Kent Allen

Journalist

Kent Allen is a longtime daily journalist and freelance writer. Over the past 20 years, while also writing about philanthropy and nonprofits, he has worked as an editor at The Washington Post, U.S. News & World Report and Congressional Quarterly. At present, Kent is a journalism and history teacher at The Field School, a middle and high school in Washington, D.C.

Lucy Bernholz

Journalist

Lucy Bernholz is a blogger and self-proclaimed “philanthropy wonk”. Her blog, Philanthropy 2173: The future of good, has been named a “best blog” by Fast Company and a “philanthropy game changer” by the Huffington Post.

Kim Breslin

Actor

Kim Breslin is an actress, comedienne, director, producer, artist, and chef. She has been an educator in North Philadelphia for 17 Years. Mother of two incredible children, she lives with her highly supportive cat, The Amazing Sid.

Cheryl Chapman

Journalist

Cheryl Chapman actively promotes philanthropy in the UK and globally via her journalism. She was the editor of Philanthopy UK: Inspiring Giving and now heads City Philanthropy, London, as its Director.

Stephen Dunn

Poet

Stephen Dunn, Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, is the author of 11 collections of poems, including “Different Hours,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 2001.

Regan Good

Poet

Regan Good is a freelance writer and poet living in Brooklyn, New York. She has written for The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times Magazine and others. She is currently at work on a memoir about growing up in a family of writers.

Sharilyn Hale

Journalist

Sharilyn Hale, M.A., CFRE is Founder and Principal of Watermark Philanthropic Advising where she offers strategies for meaningful giving, receiving and leading. A practitioner, author and educator, she brings a global perspective on philanthropy having served the nonprofit sector across North America, Bermuda and the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. She holds a graduate degree in Philanthropy & Development and is past Chair of CFRE International, the global certification for professional fundraisers setting standards for ethical and accountable practices.

Crystal Hayling

Journalist

Believer in a better world. Uppity advocate for social change. Former philanthrapoid. Crystal lives in Singapore where she helps donors develop strategy for effective grantmaking. She serves on numerous boards, and is a speaker and writer on civil society. Twitter: chayling

Holly Howe

Journalist

Holly Howe is a strategic communications consultant with a particular focus on the arts. She works as a freelance journalist, writing for various publications including FAD, RWD, House (published by the Soho House group) and the Irish Examiner. She also runs the Culture Vultures, a networking group for people in media and the arts. She can be found tweeting at @ hollytorious and in her occasional spare moments, she posts on her blog www.postcardsfromholly.blogspot.com

Wangsheng Li

Journalist

Wangsheng Li is president of ZeShan Foundation (Hong Kong) and a Senior Fellow of the Synergos Institute (New York City).

Lisa Macdonald

Journalist

Lisa MacDonald is a freelance writer and editor based in Toronto. A passion for philanthropy drives her involvement in initiatives that bring information and innovative ideas to Canada’s nonprofit sector leaders. Tweet her at @lisalmacdonald.

Andrew MacLarty

Actor

Andrew MacLarty is a New York based actor who has appeared on Boardwalk Empire and White Collar. Non-profit work includes narration for Partnership for a Drug-Free America, performances at the United Nations for Hurricane Katrina relief benefit shows, and Barefoot Theater Company’s ROCKAWAY benefit for Hurricane Sandy victims.

Bruce Makous

Journalist

Bruce Makous, ChFC, CAP, CFRE, has been a professional fundraiser for over twenty-seven years, with leadership positions in major educational, healthcare, and arts organizations. In 2009, he was named by the Nonprofit Times one of the “Most Influential and Effective” fundraisers in the US.

Peter D. Michael

Actor

For over 20 years, Peter D. Michael has been an established actor, voiceover talent and stand-up comedian. He is also an Emmy award winner.

Suzanne Reisman

Journalist

Suzanne is a U.S. international private client lawyer based in London. Suzanne assists philanthropists, their foundations, and international charities with cross-border philanthropy.

Julie Shafer

Journalist

Founder of Julie Shafer Development + Philanthropy, a national philanthropy consulting firm. Ms. Shafer offers a multifaceted skill set honed throughout 20 years as a philanthropy executive bringing a translational approach that bridges the gaps between philanthropists and non-profits.

Jade Shames

Playwright

Jade Shames is an award-winning writer living in Brooklyn, NY. His work can be found in The Best American Poetry blog, The LA Weekly, HOW art and literary journal, and more. He was awarded a creative writing scholarship to attend The New School where he received his MFA.

Amy Singer

Journalist

Amy Singer teaches Ottoman and Turkish history, as well as courses on Islamic philanthropy and the history of charity in the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University. Her recent publications include the book "Charity in Islamic Societies", and in 2008 she was awarded the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Award.

Sharit Tarabay

Artist

Sharit Tarabay painted the portrait of Gerry Lenfest. He is a painter and illustrator living in Montreal. He has his works published in magazines and books around the world.

James V. Toscano

Journalist

Jim Toscano is a principal in the consulting firm, Toscano Advisors, LLC, and an adjunct professor at the School of Business, Hamline University. Recently retired as president of the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, the cardiovascular research and education center of Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, he is a past chair of the Minnesota Charities Review Council and board member of Minnesota Council of Nonprofits.

Susan Yu

Journalist

Susan Yu is a journalist from the San Francisco Bay Area. She is an award-winning news reporter who was formerly based in Hong Kong for 14 years covering stories in Asia for international news media organisations. She is currently based in the United Kingdom where she freelances as a writer, editor and documentary film producer.

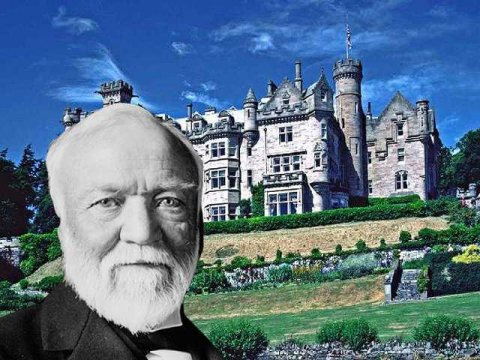

Skibo Castle

By Doug White

Andrew Carnegie’s Scottish Home

Skibo Castle takes its guests back in time in a way few places can. In the late 19th century Andrew Carnegie saved the the 800-year-old estate from almost certain ruin. Today, the nearly thousand year old estate is home to the Carnegie Club, one of the most exclusive of its kind in the world. Basking in its unique old-world charm, guests are treated to a lifestyle that even today’s wealthiest wish to duplicate. Skibo’s magic isn’t derived simply from its huge but cozy digs or its elite golf course and horseback riding opportunities; the site’s essence is a combination of all those things along with a special sense of place that exists beyond its geography, far from the madding crowd of Scottish Highlands.

The club’s founder, Peter de Savary, who bought the castle in 1982 directly from the Carnegie family, has said that coming “upon [it], with all its majesty, gives a glimpse of what it was like to live and be a house guest a hundred years ago. It doesn’t matter who you are or what you have in this world, it’s pretty hard to repeat what you find at Skibo Castle.”

The experience comes as close as anything could—even in the most pleasant of imaginations—to the response Carnegie once provided when he was asked if he feared death: “Why should I fear death, for I here at Skibo have a foretaste of the heaven to come.”

Ambassadors for Philanthropy?

By Dame Stephanie Shirley

The British Government’s Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy revisits her appointment.

The call from the Cabinet Office came in March 2009. Would I be interested in being appointed as Britain’s first- ever Ambassador for Philanthropy? Many said, after the fact, that I was a logical choice: I was self-made and had given generously to autism research and technology and was at home talking about all aspects of giving. I weighed the offer for about five minutes, and promptly signed on.

In the end, the position turned out to be both more and less than I initially imagined. We had few victories in a push to truly unleash giving in Britain. A year is a very short time. But, while the ambassadorship expired with the Labour government in 2010, it led to a number of developments that continue to this day.

It wasn’t long after taking the honorary position that the penny dropped—literally. I’d assumed that the undertaking would be allocated some funds for expenses, travel, and related activities such as research and aggressive outreach. However, I learned, the maximum government contribution would be roughly £10k and that amount was meant to cover the overhead for meetings in Admiralty Arch, at the time a government owned, iconic building in central London, and cups of tea for my guests.

Ultimately, I met the direct costs—approximately £250,0000—myself. And while Prime Minister Gordon Brown did finance a promotional video endorsing my ambassadorship, I was mostly on my own, and that fit the entrepreneur in me just fine. Because the ambassadorship itself was ill-defined, its existence was never properly discussed, evaluated, or, for that matter, acknowledged. I’d hoped that Whitehall would supply data to support the work, but they didn’t seem to know how much the government itself was allocating to “good works.” And agencies that did give significantly to developing countries, such as the Department for International Development, were looked at disapprovingly as overstepping colonialists.

Then an election was announced, and everything stopped. The office of the Ambassador for Philanthropy was closed officially nearly as abruptly as it was announced. But the closure didn’t stop us from carrying on privately and forming a purpose driven enterprise under the name— Ambassadors for Philanthropy—with a manifesto of unleashing giving worldwide.

When we set out, I’d known that the non-profit sector had a voice, and financial institutions and their philanthropic advisors, including attorneys, had a booming one, but philanthropists themselves were often unheard and underreported. With the Ambassadorship and after, I decided to focus our attention on philanthropists and giving them a voice.

Historically, the British rarely talk about money or what we do with it. To a degree, we began to change that paradigm. We promoted philanthropy as an activity to be enjoyed and celebrated and urged media outlets to report on philanthropists as individuals whose generosity should be examined as to its success, intention and impact, rather than solely as people whose wealth should be coveted. I delivered some 40 speeches throughout the country to promote this view. We persuaded philanthropists who’d never before discussed their giving publicly to speak up on camera. And when other countries expressed interest, our movement began to grow, initially within the Commonwealth, and then eventually worldwide.

Although the initial position was a creation of the British government, we were able to evolve and activate many of the ideas that emerged from the experience, including the curation of the digital publication you are now reading.

And while we didn’t provide the type of transformational change we’d hoped for in Britain, we at least helped preserve the benefits of philanthropy within the country. In mid-2012, the Conservative government proposed a tax action that would have sharply curtailed incentives for donors to give and give generously. Thankfully, we were able, along with others, including our network of philanthropists, to rally strong opposition to this measure, and the plan was eventually scrapped.

The philanthropist voice lives on!

Christopher Hohn

By Cheryl Chapman

Together with his recently divorced wife Jamie Cooper-Hohn, Chris Hohn has built up one of the largest charities in Britain.

Until recently, London hedge fund manager Chris Hohn was private to the point of reclusiveness, the philanthropic fund he shared with his wife one of the few public things about him. In November, a record-breaking divorce settlement between Chris and Jamie Cooper-Hohn made headlines after a judge ordered Hohn to pay out $531 million of a fortune that had topped out at $1.3 billion previously. The next month, news trickled out that Cooper-Hohn had chosen not to appeal the decision.

The divorce offered details about the couple’s 17-year marriage and a focal point throughout was The Children’s Investment Fund that they founded together and where Cooper-Hohn served as chief executive until 2012. The fund was established more than a decade ago and with its current endowment of $4.6 billion it has fast become one of Britain’s biggest charities. For years, until recently, the money was fed into the charity on a contractual basis from Hohn’s wildly successful hedge fund management firm TCI. Last June, The New York Times characterized the early divorce proceedings as the source of a split between the fund and the foundation and announced that Hohn had decided to end the contractual donation agreement. Leading up to the announcement, TCI had already pumped just under $2 billion into the charity over a ten-year span, easily making Hohn as one of the most generous philanthropists in the U.K.

From the start, TCI channeled 0.5 per cent of its assets each year to CIFF, which last year donated $123.8 million to causes such as child survival and early learning, and gave out another $106.4 million in grants.

According to The Financial Times, Hohn established the donative formula to make himself work harder—although, given his career, it’s unlikely he’s ever lacked motivation. He grew up in humble circumstances, the son of a secretary and a Jamaican-born car mechanic who immigrated to England in 1960. His grades were impressive enough to propel him into Harvard Business School, where he met Cooper-Hohn.

TCI and CIFF shared a similar business approach with a high risk formula at the forefront. TCI, which at one point was the world’s largest activist hedge fund and now manages assets of around $12 billion, has become notorious for its aggressive investment strategy, particularly towards state-held companies undergoing privatization, such as Britain’s Royal Mail. (Hohn's firm has emerged as the Royal Mail's largest private shareholder in recent years.)

Institutional Investor called Hohn specifically “a fearsome corporate agitator” and a German executive who fell prey to his tactics characterized him as “a locust.” CIFF, for its part, states it “invests where the evidence indicates that there is the potential to make the greatest difference. We expect to affect decision-making about resource allocation and policy at the highest levels of influence, and to shape the implementation of large scale programs in key geographies.”

The foundation works with governments and NGOs to maximize the effects of its direct investments in a way they hope will catalyze programs that sustain themselves. In an effort to de-worm schoolchildren in Kenya, CIFF is operating on a scale that aims to treat more than 5 million children annually and establish a self-sustaining operation within the country with the capacity and infrastructure to guarantee permanent control of the problem. The fund has also invested in perinatal mortality, acute childhood malnutrition, and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV/AIDS in countries such as India, Kenya, Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe. CIFF has also added two other strategic priority areas under the rubric of climate change and energy transformation.

For each of its programs, CIFF has developed a series of success measures to determine the depth of the problem, the scalability of its own approach, and the impact that can be expected.

Even without TCI’s contractual donations to CIFF, discretionary gifts aren’t out of the question. More importantly it seems, the foundation is already large enough to sustain itself as a mainstay. One of the most revealing details about the couple’s recent divorce wasn’t the shocking settlement figure, but the simplicity of their shared philanthropy. “Our family had three pillars at its core: work, philanthropy, and the care and nurturing of our children,” Cooper-Hohn said around the time of the settlement announcement. “I was primarily responsible for two of those — raising four children and, as C.E.O. and founder, creating one of the world’s largest and most impactful foundations.”

Lady Natasha Ri Isaacs & Lavinia Brennan

By Luke Norman

In a crusade to raise awareness of human trafficking, Lady Natasha and Lavinia Brennan found the power of the celebrity-crazed press to be their greatest weapon.

“We won a United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking (UN-GIFT) award before we’d even sold our first dress!” That's a boast delivered with delightful innocence by Lady Natasha Rufus Isaacs, co-founder of Beulah, a small London-based fashion label that continues to land outsized punches in its fight to combat the horrors of human trafficking.

Beulah’s story is more than a little infectious. Its journey—perhaps more fairly described as a sprint—from idea to global recognition epitomises a type of philanthropy impressive in its immediacy and impact. Beulah had yet to make its first sale when the company received a formal nod of approval from the United Nations in January of 2010. Despite the startup’s lack of employees and being run from a parent’s basement, Beulah was news.

The label launched with the consciously one-dimensional public purpose of raising awareness of modern slavery. Largely thanks to the duo’s network, Beulah was able to almost instantly deliver their message through enviable channels.

Quickly, with star customers from Sarah Jessica Parker to Kate Moss (via Pippa Middleton), famous bodies were snapped in its clothes. And alongside each mention of the shade of silk that Demi Moore sported was often a reference to the company itself. With the attention of febrile, fashion-obsessed teenage girls as well as seasoned Hollywood fashionistas, the outrage of human trafficking hit fertile, new minds. The company boasts more than 600 pieces of individual coverage in publications like Vogue, Harpers, and Cosmopolitan. In kind, their butterfly-logoed brand has built a life of its own.

Surprisingly few people are aware of the prevalence of modern slavery. In 2010 the UN reported that human trafficking represents a $32 billion-a-year industry in more than 130 countries. Beulah’s founders were as ignorant as everyone else until a months long visit to the Atulya slum in Delhi, where they volunteered at an aftercare center for female victims of the sex trade. Appalled by the realities they’d never considered, the pair resolved to shed light on the widely ignored practice.

“People seem to love the story behind the brand,” Rufus Isaacs says. The potency of their message has captured their clientele, and their own social circle, which includes both Prince William and Prince Harry, has similarly dazzled the tabloid press. With the added nuance of their shared Christian faith, the brand has been ripe for widespread publicity. Perhaps most importantly in the long run, Beulah’s product quality may be its quietest source of pride. This latter fact is a further credit to both women, both of whom share a lack of professional fashion experience.

“We’ve been very lucky,” Rufus Isaacs admits. The Beulah founders have cleverly leveraged the press attention that they hadn’t expected. When Kate Middleton chose to wear a Beulah design on her first official tour of South East Asia with Prince William, recognition of the label soared.

As is the case in much social entrepreneurship, Beulah has implicitly traded commercial viability for a tangible impact. (In the four years since its inception Beulah has yet to turn a profit.) And, for once, Britain's tabloid press is performing a public service.

Sir Winston Churchill

The mighty lion's most famous philanthropic quote.

Marcelle Speller's Ambitions For Localgiving.com

By Marcelle Speller

Why small charities sometimes matter the most

Giving is always good, but if you harness your passion, make the best use of your skills and talents, and try to avoid your weaknesses, your giving can become more focused and effective.

My money came from the sale of Holiday-Rentals.com in 2005. I had co-founded the business in early 1996 and it became the first European website for renting holiday homes shortly after. At 55, I felt I was too old for another dot-com start up, but with no kids or other financial commitments, I wanted to do something “worthwhile.” I never called it “giving back” because I don’t consider that I ever “took.” Holiday-Rentals.com generated jobs, rental income for our advertisers, great value holidays for our online visitors, a continuing income stream for the company that acquired us, and I paid a lot of tax!

I worked with a few charities and made some random donations, but somehow it wasn’t very satisfying. Then I went to a workshop at the Institute of Philanthropy which was truly inspirational. It was a three-week workshop over nine months in the UK, Vietnam, and New York. Wherever we went I was continually impressed by local charities. They work at the rock face, know best about what is needed in their communities, do long lasting work with minimal resources, and, as they live in the community, remain at the front line of accountability. They have no place to hide if things go wrong. I’d found my passion!

But I’d also discovered my weaknesses: I’m hopeless in the heat, suffer badly from jet lag, and am ever susceptible to “Delhi belly.” As a result I decided to concentrate my giving at home in the UK. I realized that, despite its status as a relatively wealthy country, there remain glaring pockets of severe deprivation here. I saw how small local charities run by increasingly unsung heroes make a huge difference inside their communities, from offering counselling services to helping older people maintain their independence or establishing sports clubs which strive to set a good example for young people. And I saw they were at risk. This was in 2008. The need in our communities was increasing, but the various grants that local charities depended on were being cut. Online giving was on the rise but also represented a threat to local charities too small to register with the Charity Commission or to claim Gift Aid, a tax incentive in the UK that can increase the value of a donation by 25%. I knew that people wanted to support their communities but saw a disconnect between donors and the charities that so often operate below the radar.

Then I had a lightbulb moment. I realized that my experience and the technical skills I gleaned from Holiday-Rentals.com could be used to connect people with their local charities. And so Localgiving.com was born. Our goal was, and remains, helping small local charities and community groups on a path to sustainability and toward less dependence on grants. We provided an online platform for one-off and direct debit donations as well as fundraising pages for their supporters.

Six years later the project has taken longer and cost more than I ever planned, and like any enterprise we’ve had challenges and setbacks.

The first challenge was a digital divide: many of the small charities lacked the digital skills or personnel to use the platform. We set up digital training workshops to equip people—often volunteers—with the digital skills needed to promote their charity through online marketing and social media. To date we have trained over 1,000 local charities.

Today over 4,000 charities and small organizations have registered on Localgiving.com but we’ve only scratched the surface. There are probably 600,000 “micro charities” in the UK. They make up 50% of our voluntary organizations but receive only 0.6% of the funding. Up to a fifth are struggling to survive.

We have to do more, but we also have to be sustainable. Currently Localgiving.com’s income comes from a £72 annual subscription fee and an additional 5% brokerage fee from donations made online through the site. The burn rate is still considerable. So we’re adapting the business model.

We have two proven approaches that we are offering to philanthropists and grant makers who are looking for a cost effective way to support local charities.

Our pioneering “Grow Your Tenner” plan works by building a national pot of matched funds and has raised over £3 million for local charities since 2012. Through a combination of Gift Aid, tax relief programs, smaller local match funds, and online donations, a single gift of £100,000 from a generous higher rate taxpayer could facilitate up to £650,000 worth of donations to thousands of local charities across the country at an initial cost of just £68,750 to the original donor. When the campaign goes live, each online donation made through Localgiving.com is matched by up to £10. The good news is that the average donation is about 50% more than the amount matched. Ultimately, “Grow Your Tenner” provides an incredibly simple and effective way to make small but effective donations to local charities on a large scale.

The second arrangement builds on our training programs by providing a package of digital skills training to help an organization raise awareness and funds online through a dedicated, locally-based project manager. A pilot program in North Yorkshire, funded by the Peter Sowerby Foundation, resulted in huge gains in confidence in online fundraising and digital donations that added up to more than the original grant amount in the first year.

So far I have invested about £3.5 million into Localgiving.com and over £7.2 million has been channelled to small local charities. That money will help them continue their amazing work and make a huge difference to their communities. That’s pretty good leverage!

By harnessing my passion and skills I’ve made my money work harder. It has given me enormous satisfaction and I’m more than a little proud of what our team has managed to achieve. But there’s a long way to go yet.

The Community Foundation

By Sandra Salmans

How a hundred-year-old idea is reshaping philanthropy around the world.

Carnegie and Rockefeller had recently established—and lavishly endowed—their eponymous foundations when Frederick Goff, president of the Cleveland Trust Company, had a different idea: a “community trust” to which the city’s philanthropists could all contribute. Interest on the money, it was declared, would fund “such charitable purposes as will best make for the mental, moral, and physical improvement of the inhabitants of Cleveland.”

Frederick-Goff

Frederick-GoffThus, 100 years ago, was born the world’s first community foundation. (Bequests were, not coincidentally, deposited at the Cleveland Trust Company—setting a precedent for the charitable funds later established by financial services companies such as Fidelity, Schwab and Vanguard.) The Cleveland Foundation was soon leaving its mark on the city, supporting the creation of the so-called “emerald necklace” of the city’s parks, shaking up the corrupt judicial system, spearheading public school reforms that included equal education opportunities for girls. And within five years, community foundations (CFs) had sprung up in Chicago, Boston, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Buffalo, NY.

The growth of CFs since then has been immense, immeasurably greater than even the visionary Goff could have dreamed. Today there are an estimated 700 CFs in the US. According to CF Insights, a consultancy specializing in community foundations, assets at CFs in the U.S. totaled $66 billion in 2013, an increase of $8 billion over the previous year. The Silicon Valley Community Foundation (SVCF) led the way, at $4.7 billion, followed by the Tulsa Community Foundation, with $3.9 billion, and the New York Community Trust, with $2.4 billion. (SVCF’s assets, which ballooned with a $1 billion gift from Mark Zuckerberg in 2013, surged ahead again in 2014 with a $500 million stake in the camera maker GoPro from its founders.)

Mark Zuckerberg

Mark ZuckerbergIn 2013, commemorating the 100 years since the first CF was established, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation created a chair on community foundations at Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. And this past October, to celebrate the centenary of the CF, the Council on Foundations gathered leading philanthropic organizations in Cleveland, where it all began.

What’s more, the rest of the world—including the developing world—is rapidly following America’s lead. According to the latest tally by WINGS (Worldwide Initiatives for Grantmaker Support), a global network of grantmaker support organizations, and the Community Fund Atlas, which is underwritten by the Cleveland Foundation, there are currently some 1,100 CFs outside the US, in more than 50 countries and on six continents. Having launched in the US and Canada in 1914, the CF crossed the Atlantic to Britain about 35 years ago, took root in Germany around the time of reunification, spread to Russia and the former Soviet states, and is currently establishing a foothold throughout the developing world. Between 2010 and 2014, eight new CFs were established in Asia-Pacific, four in sub-Saharan Africa, four in Latin America and two in the Middle East. As the Mott Foundation aptly declared in its 2012 annual report, CFs are “rooted locally, growing globally.”

Whether in the industrialized world or the emerging one, CFs are identical in one key respect: They are public charities that tap the wealth of their communities, with the goal of redistributing it locally. That mission has universal application, asserts Emmett Carson, who is the SVCF’s chief executive officer and is also the visiting holder of the new Mott chair on community foundations. “We should think of the community foundation concept like water,” he says. “The water is the same, but it takes on the shape of whatever community you pour it into.”

Emmett Carson

Emmett CarsonAnd the fact is that CFs differ markedly from one country to another—and, increasingly, even within a country. In the developed world, many CFs are taking on a more activist role than in the past, initiating projects and partnerships as well as donating to established programs. What’s more, many are traveling far beyond their borders, accepting funds from a wider audience and playing a role on the national and even international stage

Meanwhile, the CFs that are springing up in less developed areas—Africa, Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe—are digging deep into their communities to convince residents to trust the very concept of pooling and distributing funds. While endowments and professional leadership are the hallmarks of long-standing CFs in the US, money necessarily takes a back seat to other priorities among CFs in emerging countries, where there are only small pockets of wealth. “They have to prove they’re relevant to the community and need to establish trust where often there are low levels of trust,” notes Nick Deychakiwsky, program officer for the Mott Foundation’s civil society team. In fact, in many cases those CFs have received a jumpstart by foundations such as Mott, Ford, Open Society and Aga Khan, and also appeal to the diaspora for funds.

Nick Deychakiwsky

Nick DeychakiwskyAs Jenny Hodgson, director of the South Africa-based Global Fund for Community Foundations, observes, community philanthropy is as old as, well, communities themselves. “Every country and culture has its traditions of giving and mutual support between family, friends and neighbors,” she has written, pointing to the tradition of burial societies across Africa and hometown associations in Mexico.

However, the new generation of community philanthropy institutions—fueled by factors ranging from a growing concentration of wealth to the popularity of social media, according to WINGS executive director Helena Monteiro—take a more strategic approach to giving. “Most are about development rather than donor services, and they do a lot of capacity building,” Hodgson told Giving. “They’re building civil society, essentially.” As the Kenya Community Development Foundation, a CF established in 1997, asserts on its website, its goal is “the growth and sustainability of communities by their strong engagement in owning and driving their development efforts.” (Italics are KCDF’s.)

Helena Monteiro

Helena MonteiroA sampling of this new breed of CFs offers a glimpse of the variety of programs being undertaken:

- In Egypt, the Community Foundation for South Sinai is working to support the Bedouin, who have long been marginalized. The CF is working on several fronts to raise the tribes out of poverty and preserve their heritage; projects have included teaching the women how to make useful wool products, and providing a camel to a boy who was his family’s breadwinner.

- In Costa Rica, the Monteverde Community Fund, initially founded to invest tourism revenue in preserving the rain forests, has added a social portfolio. Among other projects, it is promoting a community Internet-based radio station, training local youth to create programming and encouraging them to engage in public discourse.

- In Romania, multiple CFs have organized annual “swimathons” to raise their profiles, garner funds and spread the ethos of sharing. In Cluj, the country’s second most populous city, revenue went to support new programs for young people, including a robotics class in an elementary school and education for students with special needs.

- On the West Bank, the Dalia Association, a Palestinian CF, gave women from nearby villages $6,000 to build a park. The women went on to secure additional donations, including the land, utility hookups, a basketball court, a playground and a library.

- In Slovakia, the Banska Bystrica City Foundation—Eastern Europe’s oldest CF, initially launched as a World Health Organization project—has assembled a group of local donors that assist the city’s street children, provide support for the local Roma community, and encourage younger people to take an interest in philanthropy.

While all these CFs have struggled to raise money, elsewhere they have also encountered tight governmental controls or opposition. Even there, however, they are making headway. According to a recent report by CAF (Charities Aid Foundation) Russia, a support group for charitable and nonprofit groups, nearly two-thirds of the membership of CF governing boards comes from the authorities and business; even so, starting with one CF in 1998, Russia today has more than 45 community foundations. The situation is more problematic in China, where very few private organizations are permitted to do fundraising, grantmaking is relatively unknown and civil society is weak. Still, says Hodgson, “everybody is talking about community foundations in China. There’s lots of energy right now.”

That’s also an apt description of the situation in the US, where the biggest CFs are stepping up their game. Rather than limiting themselves to making grants to established programs, “community foundations are increasingly moving into the sphere of brokers for community solutions,” declares Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker, who heads the Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo in New York State. Dedecker’s group was the prime mover in launching Say Yes to Education, an initiative that has brought together school parents, union leaders, the business sector and other stakeholders to provide year-round support to students K-12, including college scholarships.

Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker

Clotilde Perez-Bode DedeckerArguably the most striking example of the supercharged CF is the Silicon Valley Community Foundation. The result of a merger of two leading CFs in 2006, SVCF is not only the largest single grantmaker to Bay Area nonprofits, it’s the fifteenth largest international grantmaker in the United States, according to Carson. Furthermore, while SVCF draws much of its wealth from the affluent high-tech community, it also has donors who neither live in the Bay Area nor give to it, but choose to use SVCF as the means to distribute their philanthropy.

To Carson and others, these developments represent a natural progression for CFs in a society that is ever more global. “People increasingly see themselves as national citizens and, more likely, as global citizens,” he notes.” And because many Americans, or at least their parents, hail from different countries, they want to be able to send money overseas as well as to contribute to their new homelands. To compete in this arena—and also to counter the inroads made by financial services companies such as Vanguard and Fidelity, which are vying for donor-advised funds—the leading community foundations are carving out a niche in international philanthropy.

To some people in the CF world, venturing so far afield seems incompatible with the very notion of a community foundation. “A part of me says, ‘Shouldn’t it all be local?’” says the Mott’s Nick Deychakiwsky. But as someone with his own strong spiritual ties to Ukraine, Deychakiwsky concedes that “we’re all living in a more globalized world.” Ultimately, he hopes, globalization will lead to US-based CFs becoming more involved with community foundations abroad—relationships that could benefit organizations in both the developed and developing world. (And there are surprising similarities: Experts notes that CFs in emerging countries have a lot in common with those in rural areas of the US such as the deep South, where “hyperlocal” community development remains the sole focus.) “It’s amazing how much is transferable,” agrees Dedecker of the Community Foundation of Greater Buffalo, who is exploring the sharing of best practices with a CF in Nottingham, England. “The universal drive is for significant change and a strong sense of place,” she concludes. “That’s what unites us all.”

Mo Ibrahim

By Jay Balfour

Ibrahim faces tough criticism of his prize for Achievement in African Leadership.

It’s not always easy giving away a lot of money, and arguably no philanthropist has learned that lesson more than Mo Ibrahim.

Born in the Sudan in 1946, Ibrahim—who describes himself in his Giving Pledge letter as “a very lucky African boy”—earned a degree in electrical engineering in Egypt; after emigrating to Britain in the 1970s, he did graduate work in engineering and mobile communications that became the basis for his career. After working for several other telecommunications companies in London, including British Telecom, he founded Celtel, which built and operated mobile networks across Sub-Saharan Africa. Less than a decade later, in 2005, Ibrahim sold Celtel for $3.4 billion. Around the time of the sale he wrote, “I had to face the big question, ‘Now what? Where to go from here?’ I knew that I needed to go back and do something for our people. It is a moral duty and African custom to look after your extended family. I felt my extended family reached from Cairo to Cape Town.”

The result was the Mo Ibrahim Foundation and its brief was to encourage better governance in Africa. To do this it created the Mo Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership, a $5 million award distributed over ten years with an additional $200,000 annual payout for life. The prize is awarded to African heads of state who “deliver security, rule of law, economic opportunity, infrastructure, management of public finance, transparency, education, health and citizens rights” to their citizens and who are elected to office and democratically transfer power to their successors. Under the scope of the foundation, Ibrahim also created an Index of African Government, a scorecard that measures more than 100 parameters of governance. Ibrahim's focus on leadership grew out of his own experience walking away from bribes and corrupt licensing deals in Africa, and business transparency became a central publicity campaign for Celtel.

The problem with the award is that the foundation has had a notoriously difficult time finding deserving recipients. Since it was launched in 2007, the prize—which dwarfs the Nobel Prize of about $1 million—has been awarded only three times. “No Mo Ibrahim Prize awarded, once again,” a headline in Al Jazeera proclaimed in 2013, the second consecutive year such an announcement was called for.

The prize was first awarded in 2007 to President Joaquim Chissano of Mozambique, and then in 2008 to Botswana President Festus Mogae. In 2011, the foundation granted former Cape Verde president Pedro de Verona Rodrigues its third prize (excluding the honorary prize it gave to Nelson Mandela the first year).

While Ibrahim and his blue-ribbon board defend their right to withhold the award, the omission year after year has heightened what was already a storm of criticism. At one point, Ibrahim asserted that spotlighting the winners helped erase the “cartoon” image of African leaders, but the shortage of winners has itself been something of an embarrassment. Furthermore, the award itself has proven highly controversial. In a piece in The New Yorker, critics asserted that the prize has been given to worthy leaders of countries that are nonetheless riddled with corruption, like Mozambique; that it has not been given to the heads of state of countries, such as Ghana, that are better-run than Mozambique; that it rewards—even bribes—people for behaving the way they’re supposed to behave; and that it “overemphasizes the power of leaders and underemphasizes the power of everyone else.” Above all, it has been suggested that, especially on a continent where poverty is rampant, the money might be better spent elsewhere. Separately, the Index of African Government has also come under fire. Critics complain that the scoring is distorted, giving equal weight to “freedom of expression” and, say, “immunization from measles.”

Ibrahim, for his part, defends both the prize and the index. He argues, with some justice, that those who equate the prize with bribery are naïve, that—unlike Western heads of state like Bill Clinton or Tony Blair—African leaders have little opportunity to make legitimate fortunes when they retire. He maintains that the important thing is to raise the bar for African leadership, even if it means often withholding the prize. And others, some of them African, say that the index, whatever its drawbacks, has influenced contributions from the West and spurred African countries to compete with each other for superior rankings.

Perhaps recognizing the prize’s limits, however, Ibrahim has also established foundation fellowships: Every year a few individuals will be paid handsomely to work for the heads of three institutions—the African Development Bank, the World Trade Organization and the Economic Commission for Africa—that have considerable sway over the future of the continent. Conceivably, those fellows could one day emerge as leaders of their countries—and recipients of the Mo Ibrahim Prize for Achievement.

In the meantime, it’s arguable that Ibrahim’s greatest contributions to democracy in Africa are the cellphones he made accessible. As The New Yorker recently noted, the Arab spring that begain in 2010 in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya was fueled by mobile phone emails, Tweets, and videos. Ironically, it’s been as a businessman, if not as a philanthropist, that Mo Ibrahim has most transformed Africa.

Louise Blouin

By The Editors

An icon of the art world is leveraging culture and creativity against global challenges.

For a woman who has spent tens of millions of dollars of her personal fortune in pursuit of cultural development, Louise Blouin has generated some surprisingly negative press. Criticisms range from those who gently mock the Miss World-esque vision statements emanating from the French-Canadian to more serious accusations of unpaid debts and financial mismanagement at her media empire.

For the former at least, one can point to the peculiarly English (the Louise Blouin Foundation is based in West London) trait of finding unabashed, highly ambitious philanthropy hard to deal with. Add the vagueness that cultural philanthropic ventures can often carry and the alleged string of celebrity lovers (supposedly including Britain’s own Prince Andrew), and you can see why the British press have so enjoyed themselves with Mrs. Blouin. However, as publisher of more than 90 art titles per year, including the magazines Art + Auction, Modern Painters, and Culture + Travel, and as founder of the hugely influential ARTINFO.com, her place as a bastion of cultural influence has long been secure.

Blouin launched her $30 million eponymous foundation in 2005 with the vague intention of “supporting cultural development across the globe, disseminating culture beyond borders and generating new knowledge about creativity.” While some of its global aspirations may have been quietly scaled back, the Foundation’s London base has become one of the largest non-government, not-for-profit cultural spaces in the world.

Nearly a decade later, the Louise Blouin Foundation (LBF) has given space to a wide range of artists around the world while also hosting think tanks, workshops, debates, and summits on all manner of zeitgeists. Her annual Creative Leadership Summit in New York brings the challenge of using culture and creativity as catalysts for positive social change to the very highest table (past awardees at the grand event have included Bill Clinton and King Abdullah of Jordan) and LBF has boasted a 46-member advisory board including artist Damien Hirst, actor Jeremy Irons, and photographer Mario Testino.

Born and raised in Montreal, Blouin’s love affair with fine art started thanks to a volunteer posting at the city’s Museum of Fine Arts. Years later, Blouin even referenced her affinity for the arts in a split from her second husband and long-time business partner, John MacBain. The pair’s company, Trader Classified Media, was valued at almost $1 billion in the late 1990s. But, since 2000, Blouin has concentrated her resources on sharing the cultural message, both through her business, Louise Blouin Media, and through her foundation.

A Blouin quote on the LBF website neatly encapsulates both her philosophy and the reasons why some find it a little difficult not to ridicule her approach: “Verse three of Genesis: Let there be light. Yes, let. And then let us see it, learn from it, take it in and start to shine.”

Whatever you might think of such a statement, there is no denying the role that organisations like LBF can play. On its opening, Saumarez Smith, the British cultural historian, offered that the LBF could one day become as important as the Guggenheim Museum.

The LBF may not have scaled those heights (Blouin might well say “yet”) but given its proprietor there seems little doubt that its impact will continue to grow. “I don’t do this for power. I have everything I want in my life. I do this to make a difference,” Blouin said recently, with customary icy determination.

Len Blavatnik

By Doug White

A Soviet emigrant to the US, Blavatnik is becoming a generous establishmentarian in education and beyond.

“Leonard Blavatnik is making possible a new way for Oxford to contribute to the world.” So began the September 2010 tribute by Lord Christopher Patten, Chancellor of the University of Oxford, in his remarks acknowledging Blavatnik’s “once-in-a-century” $120 million gift, which established Europe’s first major school of government at the oldest university in the English-speaking world.

Blavatnik, like many other donors with an eye on making transformational gifts, is not new to philanthropy.

Through his family foundation, he recently donated $50 million to fund the “Blavatnik Award for Young Scientists” at the New York Academy of Sciences. The money is helping to expand the number of people who are eligible to receive the award, which will now be open to faculty-rank scientists across the United States age 42 or under. The idea of “young” is key. According to Eric Lander, a director of the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, “Young scientists drive scientific discovery and innovation. They feel urgency and impatience. They think creatively and boldly. While we must support promising scientists at all levels, young scientists are a critical resource that we must nurture for the good of the whole scientific enterprise.”

But while academic pursuits feed the mind and eventually improve lives, Blavatnik is also putting his money where it will have immediate impact on people who desperately need it. He gives much every year to Colel Chabad, an Israeli charity that operates a network of soup kitchens and food banks, dental and medical clinics, daycare centers, widow and orphan support, and immigrant assistance programs. Founded in 1788, Colel Chabad is the oldest continuously operating charitable organization in Israel. Blavatnik’s support provides food every month for 5,000 families in 25 Israeli cities and towns.

In 1978, during a period of mass emigration for Soviet Jews, Blavatnik left his home in the Soviet Union for the United States. After then earning advanced degrees at Columbia and Harvard, his business career took off. He founded and is chair of Access Industries, a privately held multi-national company headquartered in New York, that invests in natural resources and chemicals, media and telecommunications, and real estate. In 2011 a subsidiary of Access bought the Warner Music Group for $3.3 billion.

As his generosity shows, Blavatnik tends not to think of starting new charitable enterprises; what makes his gifts noteworthy is his well-funded focus on improving what’s already working. There might be no better example, and thus an explanation for his comfort in giving away so much of his wealth, than his bet on one of the world’s premier educational institutions—a grand gesture meant to fuse history with the future. In Lord Patten’s words: “Oxford will now become the world’s leading center for the training of future leaders in government and public policy—and in ways that take proper account of the very different traditions, institutions and cultures that those leaders will serve. It is an important moment for the future of good government throughout the world.”

True enough. But even so, his gifts might say as much about the man, and his vision of what’s right in the world, as it does about the institutions that he supports.

Lord David Sainsbury

By Luke Norman

Sainsbury's Gatsby Foundation has spent more than fifty years at the cutting edge of British philanthropy.

"Impact" may be the buzzword in philanthropy these days, but it’s been at the forefront for nearly half a century for David Sainsbury, now Baron Sainsbury of Turville, whose great-grandfather founded the behemoth supermarket chain. Sainsbury’s Gatsby Charitable Foundation identifies a few tightly-focused areas and creates long-term projects to achieve its goals.

Some 42 years after Gatsby’s first grant—£50 to the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine—Sainsbury in 2009 became the first Briton whose cumulative donations topped £1 billion. That money is directed into five major areas: basic plant science and neuroscience research to improve food security and mental health; agriculture development in Africa; scientific and engineering education; the Institute for Government and the Centre for Cities; and the arts, which is the particular interest of Sainsbury’s wife, Susie.

Its founder’s years in politics arguably influenced Gatsby’s strategic approach. Sainsbury, born in 1940, was an early member of the short-lived Social Democrat Party in 1981, ultimately rejoining Labour in 1996. As Minister for Science and Innovation, he was the third longest serving minister in Tony Blair’s government.

With that track record, Sainsbury had plenty of time to work out how best to steer major policy change. Accordingly, waiting for the right project to come along isn’t the Gatsby style. Sainsbury maintains that “private foundations should see part of their role as being, in some sense, a research and development arm of the government.” But because foundations such as Gatsby are private, they can often get out ahead of government.

And in some cases, they seek to tell government what to do. Presumably as a reflection of Sainsbury’s years in government, Gatsby has funded two initiatives: the Institute for Government, which works with political parties in Westminster and senior civil servants in Whitehall, to make government more effective; and The Centre for Cities, which produces practical research and policy advice aimed at helping Britain’s cities improve their economic performance.

Some of Gatsby’s projects operate at the scale one might expect of government undertakings. The Sainsbury Laboratory Cambridge University, for example, is home to more than 150 scientists researching plant growth and development, whose mission is to increase agricultural productivity, but in an environmentally sustainable way. Another huge, capital-intensive project is the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour at University College London, scheduled to open this year. With such large-scale investments, Sainsbury often seeks to make his money go farther by partnering with a like-minded organization—in this case, the Wellcome Trust.

Gatsby’s efforts range from the building of internationally recognized centers of excellence to smaller-scale educational initiatives. For instance, in the late 1990s there was a widely acknowledged shortage in the UK of qualified graduates for STEM (science technology, engineering, math) jobs. Gatsby highlighted the need for an improved program of practical science in secondary schools, with research that showed about one-quarter of UK schools serving 11-to-16-year-olds lacked even a single physics teacher. Last year, more physics teachers were being trained in England than at any time in the previous 30 years.

When it comes to impact philanthropy, that’s as good as it gets.

Fred Mulder

By Lisa MacDonald

Founder, backer, and global ambassador of The Funding Network, Fred Mulder explains his commitment to social giving and crowd funding.

Frederick Mulder doesn’t understand why people aren’t more willing to be vocal about their charitable activities. For this Canadian-born art expert, the idea that giving should be done privately and without publicity has become antiquated. As a lifetime giver, Mulder is now putting his mouth where his money is.

As a young boy growing up in the Midwestern Canadian province of Saskatchewan, Fred Mulder was taught that tithing—the act of giving a portion of one’s income to the church—was normal and commendable. While education may have led him away from organized religion, his commitment to giving hasn’t wavered.

An early experience as a donor directed Mulder toward the benefits of collaborative giving. “I had a sense of being taken advantage of after a charity that I donated to went bankrupt,” he said. “They hadn’t told me that they were in any kind of financial difficulty and it occurred to me that it wouldn’t have happened if I had a peer group to check things out with...doing the kind of due diligence that you must do.”

That incident led the internationally recognized art dealer, who lives in London, to form two organizations that follow a crowd funding model: The Network for Social Change, the first giving circle of its kind in the UK, and The Funding Network, now a global organization he describes as “the friendly Dragons’ Den”—a version of the popular reality show where visitors pitch their business ideas to a forum of investors—“for charities and potential donors.”

If Mulder’s approach to crowd funding has a calling card, it is its emphasis on live collaboration in place of online anonymity. “I don’t find it interesting or inspirational to give online,” he admits. “I love to hear from the people who are doing the work and meet them. I wish more people were setting up structures like mine, or one of their own imagining. There is still a ways to go.”

Although he supports many social causes, he stresses his primary attachment is to people. For Mulder, social giving is not only about leveraging money, it’s about creativity and entrepreneurship. “It’s like sitting on a teeter-totter,” he muses. “You need to put effort into finding a ‘heavy’ to tip the balance on the other side.”

His artful approach is now a signature. After a Greenpeace ship, the Rainbow Warrior, was sunk in Auckland Harbor in 1985, he suggested using front-page advertising to attract new members. He took the risk of underwriting the campaign and was thrilled with its success. “It gave me a kick that an ordinary member of the public with £10,000 could take a risk on behalf of a charity, and that it worked out!” On another occasion, he became the news himself when he announced that most of the proceeds from his sale of Picasso’s 1935 etching, La Minotauromachie, would be donated to charity.

Mulder is in philanthropy for the long haul. In his role as global ambassador for The Funding Network, he continues to support the platform as it becomes more established around the world. Closer to home, he endowed his own Frederick Mulder Charitable Trust with £5 million in 2012 to be allocated to charities over the following 10 years. That his three children are trustees offers new challenges for the veteran philanthropist. “They’re quite tough on me actually—asking a lot of awkward questions. But it’s great. We are four busy people leading very different kinds of lives but linking over similar issues.”

Matchmaker

By Ron Finlay

Facilitating professional volunteering is growing in popularity in the UK as an answer to 21st century life pressures.

Big change is happening in Britain’s volunteering. As baby boomers move into their sixties, the traditional notion of charity volunteers being ladies helping out with admin tasks or assisting in charity shops is fast giving way to the rise of the professional volunteer – as often male as female.

These pro bono workers, with years of experience behind them, naturally want to put their skills to good use. But how do they find the right match, and fit new voluntary commitments into lives that remain full of other 21st century pressures?

You might imagine that demand for their services would be overwhelming. With 165,000 registered charities in the UK, and an economic climate that, despite the recent upturn, remains really challenging for the third sector, there is certainly plenty of need for skilled business people. But those who need it most – small to medium-sized charities and community groups that are struggling to generate income and plan strategically – are usually the least able to articulate their requirements. They often just don’t have the time or the mindset to ‘go to market’.

This is where ‘brokers’ really come into their own.

These modern-day matchmakers not only identify the frontline welfare organisations that need support, but also help them specify the services they require in such a way that fit with what professional volunteers can offer.

As with any good betrothal, after the match has been made, the broker’s role is to support the couple in the early stages of their relationship. Really important to secure the buy-in of the professional volunteer is to design their input so that they can donate small ‘bursts’ of high impact time on a regular basis for a fixed term.

“Running a strategy workshop for a charity board is really rewarding,” says Sue Davidson, who has been bringing her C-suite experience from international organisations to small charities for over two years. “The last thing I want is an open-ended low value commitment, but if I can help trustees secure a better future for their charity, it’s a win-win for them and me.”

The matchmaker will also help out by drawing on further resources if a charity requires more time and skills than a single volunteer can provide, freeing each side from a possible guilt-trip.

The success of the model is clear. While overall volunteering in Britain has remained fairly static over the last few years – with 29% of the population volunteering regularly – at The Cranfield Trust, we’ve seen our volunteer register grow 15% year-on-year.

Amanda Tincknell, Cranfield Trust

Amanda Tincknell, Cranfield Trust

It’s a different kind of philanthropy. Frontline charities benefit from an injection of high value skills, and the contributing business people build their networks and knowledge while deriving satisfaction from the volunteering experience. As Sue says ‘I like working with clever, motivated, driven people. I would really encourage those in the private sector with years of transferable experience to give their time.’ The Royal Voluntary Service estimates that British volunteering by people aged 50 and over will grow in value from £10bn to £15bn by 2020. Much of this will be by those offering professional skills. Long live the matchmaker!