About

Global Team

Roberta d’Eustachio

Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Roberta d'Eustachio (Rd'E) is an entrepreneur obsessed with delivering media from the social investor/philanthropist's point of view. That desire led to founding The American Benefactor, the first consumer magazine for philanthropists, as well as Giving Magazine and each of its subsequent evolutions: from print, to digital, to mobile with Facebook Instant Articles, delivering stories of social impact - for everyone, everywhere.

Rd'E has consulted with, and/or received investment from, leading global brands, including: The Economist, the Financial Times, Euro Money/Institutional Investor, the Pitcairn Family Office, Fidelity Capital and the World Bank as well as philanthropists and social enterprises around the world.

After serving as chief-of-staff to Dame Stephanie Shirley, the British Government’s Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy, Rd'E founded the AmbassadorsForPhilanthropy.com enterprise to give social investors a voice worldwide.

Dame Stephanie Shirley

Philanthropist & Believer-in-chief

Dame Stephanie “Steve” Shirley is a British entrepreneur turned philanthropist. She originally arrived in London as an unaccompanied Kindertransport child refugee from Austria during WWII. “Steve” was an early pioneer in technology and, after taking her company public, she has given more than $100 million to organizations that specialize in autism research and technology, including founding the Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University. Appointed by Prime Minister Gordon Brown to the title of the British Government's Founding Ambassador for Philanthropy 2009-2010, she believes in the advancement of the philanthropist voice worldwide.

Her memoir “Let It Go” was recently published, chronicling her life so far.

"Steve" is the Believer-in-chief to Giving Magazine, providing the means to imagine and execute its potential to the fullest.

Jerry Alten

Chief Curator

Jerry Alten is a world-renowned art director of magazines, across all devices, and other marketing and advertising work, winning many prizes in the media field. Under Walter Annenberg’s ownership of TV Guide, Jerry took the circulation from 5 million up to 19 million during his tenure as art director. He continued to work with Rupert Murdoch’s organization after the buy out of TV Guide and created the first interactive website for the magazine. Jerry was also the original investor in The American Benefactor Magazine and art director, which succeeded in obtaining more than $7 million worth of investment from Fidelity Investment's venture firm.

Brian Lipscomb

Chief Technologist

Brian Lipscomb has been involved with technology for over twenty years, and founded technology services company Divergex, based in Philadelphia. Specializing in all aspects of computers, Brian brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise to Giving Magazine. His philosophy is: “Do it right, or don’t do it at all.”

Lipscomb adds: “Technology is a constantly evolving industry. People who use technology daily don’t have the time to study and learn all of the new and different terms and capabilities. I work to show people how technology can improve their efficiency, productivity and, ultimately, their lives.”

Jay Balfour

Managing Editor

Before Jay became the Managing Editor for Giving, he was a freelance writer and editor based in Philadelphia. With an academic background in Philosophy he leverages an informed perspective on everything from African music to youth movements in the West for several publications both online and in print. At Giving Magazine he shares a passion for unabated reporting and the ushering in of a new age in philanthropy.

Sandra Salmans

Executive Editor

Sandra Salmans is a New york-based writer and editor who works primarily in the nonprofit field. She began her career as a business and financial journalist at Newsweek and The New York Times, but has also covered national news, education and the arts. Prior to going freelance, she was a senior officer in communications for a leading foundation in Philadelphia.

Nicole Raeder

Digital Design Manager

Nicole delights in great design. That's why her commitment is compulsive; contagious even, to get it right. Or, change it. Or, change it again. Whatever is required to finding the way to the end point, which is sometimes the beginning. In other words, she never gives up, or stops, till the thing clicks.

She also loves cats.

Damon d'Eustachio

Co-Director, Global Membership

A foodie who navigated his way from the city of brotherly love to Charleston, S.C, Damon is devoted to serving nonprofits worldwide that believe the philanthropist voice must be heard.

Damon graduated from the College of Charleston in Art Administration and performed an internship at London’s prestigious Tate Gallery’s New York City office.

Jessica Lambrakos

Co-Director, Global Membership

Jessica is responsible for the management and development of the Global Awards for nonprofits of Giving Magazine for their nominated philanthropists and supporters.

She also serves as founder and executive director of her own nonprofit, “The Naked Truth AIDS Project”, which raises funds for AIDS prevention education programs in the USA as well as Africa.

Nick Cater

Contributing Editor

Nick Cater is a UK-based international writer and editor. A former Fleet Street journalist, he has reported from more than 40 countries so far on stories as diverse as war in Africa, environmental risks in Latin America, disasters in Europe, and the Asian sport of elephant polo.

Luke Norman

Senior Editor

Luke Norman is an experienced journalist and corporate social responsibility consultant. Having started at The Daily Telegraph, Luke has worked for a wide range of international media outlets before moving into the heady world of multi-national corporations and their sustainability commitments. Luke has transplanted himself and his family from London to Rio de Janeiro, where the views he now observes are deliriously engaging.

Doug White

Senior Editor

Doug White, a long-time leader in the nation's philanthropic community, is an author, professor, and an advisor to nonprofit organizations and philanthropists. He is the director of Columbia University's Master of Science in Fundraising Management program. He also teaches board governance, ethics and fundraising. His most recent book, “Abusing Donor Intent,” chronicles the historic lawsuit brought against Princeton University by the children of Charles and Marie Robertson, the couple who donated $35 million in 1961 to endow the graduate program at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Kent Allen

Journalist

Kent Allen is a longtime daily journalist and freelance writer. Over the past 20 years, while also writing about philanthropy and nonprofits, he has worked as an editor at The Washington Post, U.S. News & World Report and Congressional Quarterly. At present, Kent is a journalism and history teacher at The Field School, a middle and high school in Washington, D.C.

Lucy Bernholz

Journalist

Lucy Bernholz is a blogger and self-proclaimed “philanthropy wonk”. Her blog, Philanthropy 2173: The future of good, has been named a “best blog” by Fast Company and a “philanthropy game changer” by the Huffington Post.

Kim Breslin

Actor

Kim Breslin is an actress, comedienne, director, producer, artist, and chef. She has been an educator in North Philadelphia for 17 Years. Mother of two incredible children, she lives with her highly supportive cat, The Amazing Sid.

Cheryl Chapman

Journalist

Cheryl Chapman actively promotes philanthropy in the UK and globally via her journalism. She was the editor of Philanthopy UK: Inspiring Giving and now heads City Philanthropy, London, as its Director.

Stephen Dunn

Poet

Stephen Dunn, Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, is the author of 11 collections of poems, including “Different Hours,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 2001.

Regan Good

Poet

Regan Good is a freelance writer and poet living in Brooklyn, New York. She has written for The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times Magazine and others. She is currently at work on a memoir about growing up in a family of writers.

Sharilyn Hale

Journalist

Sharilyn Hale, M.A., CFRE is Founder and Principal of Watermark Philanthropic Advising where she offers strategies for meaningful giving, receiving and leading. A practitioner, author and educator, she brings a global perspective on philanthropy having served the nonprofit sector across North America, Bermuda and the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. She holds a graduate degree in Philanthropy & Development and is past Chair of CFRE International, the global certification for professional fundraisers setting standards for ethical and accountable practices.

Crystal Hayling

Journalist

Believer in a better world. Uppity advocate for social change. Former philanthrapoid. Crystal lives in Singapore where she helps donors develop strategy for effective grantmaking. She serves on numerous boards, and is a speaker and writer on civil society. Twitter: chayling

Holly Howe

Journalist

Holly Howe is a strategic communications consultant with a particular focus on the arts. She works as a freelance journalist, writing for various publications including FAD, RWD, House (published by the Soho House group) and the Irish Examiner. She also runs the Culture Vultures, a networking group for people in media and the arts. She can be found tweeting at @ hollytorious and in her occasional spare moments, she posts on her blog www.postcardsfromholly.blogspot.com

Wangsheng Li

Journalist

Wangsheng Li is president of ZeShan Foundation (Hong Kong) and a Senior Fellow of the Synergos Institute (New York City).

Lisa Macdonald

Journalist

Lisa MacDonald is a freelance writer and editor based in Toronto. A passion for philanthropy drives her involvement in initiatives that bring information and innovative ideas to Canada’s nonprofit sector leaders. Tweet her at @lisalmacdonald.

Andrew MacLarty

Actor

Andrew MacLarty is a New York based actor who has appeared on Boardwalk Empire and White Collar. Non-profit work includes narration for Partnership for a Drug-Free America, performances at the United Nations for Hurricane Katrina relief benefit shows, and Barefoot Theater Company’s ROCKAWAY benefit for Hurricane Sandy victims.

Bruce Makous

Journalist

Bruce Makous, ChFC, CAP, CFRE, has been a professional fundraiser for over twenty-seven years, with leadership positions in major educational, healthcare, and arts organizations. In 2009, he was named by the Nonprofit Times one of the “Most Influential and Effective” fundraisers in the US.

Peter D. Michael

Actor

For over 20 years, Peter D. Michael has been an established actor, voiceover talent and stand-up comedian. He is also an Emmy award winner.

Suzanne Reisman

Journalist

Suzanne is a U.S. international private client lawyer based in London. Suzanne assists philanthropists, their foundations, and international charities with cross-border philanthropy.

Julie Shafer

Journalist

Founder of Julie Shafer Development + Philanthropy, a national philanthropy consulting firm. Ms. Shafer offers a multifaceted skill set honed throughout 20 years as a philanthropy executive bringing a translational approach that bridges the gaps between philanthropists and non-profits.

Jade Shames

Playwright

Jade Shames is an award-winning writer living in Brooklyn, NY. His work can be found in The Best American Poetry blog, The LA Weekly, HOW art and literary journal, and more. He was awarded a creative writing scholarship to attend The New School where he received his MFA.

Amy Singer

Journalist

Amy Singer teaches Ottoman and Turkish history, as well as courses on Islamic philanthropy and the history of charity in the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University. Her recent publications include the book "Charity in Islamic Societies", and in 2008 she was awarded the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Award.

Sharit Tarabay

Artist

Sharit Tarabay painted the portrait of Gerry Lenfest. He is a painter and illustrator living in Montreal. He has his works published in magazines and books around the world.

James V. Toscano

Journalist

Jim Toscano is a principal in the consulting firm, Toscano Advisors, LLC, and an adjunct professor at the School of Business, Hamline University. Recently retired as president of the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, the cardiovascular research and education center of Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, he is a past chair of the Minnesota Charities Review Council and board member of Minnesota Council of Nonprofits.

Susan Yu

Journalist

Susan Yu is a journalist from the San Francisco Bay Area. She is an award-winning news reporter who was formerly based in Hong Kong for 14 years covering stories in Asia for international news media organisations. She is currently based in the United Kingdom where she freelances as a writer, editor and documentary film producer.

Queen Rania Al Abudullah

By Sandra Salmans

Jordan's queen challenges stereotypes in the Middle East and beyond.

A “mum and a wife with a really cool day job” is the way Queen Rania al Abdullah of Jordan sums herself up on Twitter. That breezy description, with its blend of tradition and technology, nicely encapsulates the way she has redefined her royal role, challenging stereotypes and changing the Arab world.

Even before she became queen in 1999, a large part of Rania’s day job involved working for the public good with a particular focus on the protection and development of children, especially girls. (It is unclear how much the royal family donates directly to the causes she champions, all of which raise funds on their own.) The Jordan River Foundation, a nonprofit she founded in 1995 and continues to chair, helps women secure employment and sell their handicrafts, but also seeks to protect children from domestic abuse; its Child Safety Center is said to be the first of its kind in the Arab world. In a similar vein, she has fought to end so-called “honor killings,” murders committed by men to punish sisters or daughters who have “disgraced” their families, often by running away with and marrying the wrong man.

The honorary chair of the United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative, she is especially passionate about education and has led efforts in Jordan to improve classroom quality, teaching standards, computer access, and family involvement. In 2008, she started the Madrasati (“My School”) Foundation, which aims to rebuild and repair some 500 underfunded local schools throughout Jordan, most notably for Palestinian youngsters in East Jerusalem. The Queen’s website champions an education-equals-opportunity formula and her stance that schooling is an inalienable right is explicit: “I believe you deserve an education. Whoever you are. It’s your right.”

Born in Kuwait to Palestinian parents, Rania Yasin, 44, had a middle-class upbringing and a Western education, including a business degree from the American University in Cairo. In 1991 she moved to Amman, where her parents had settled after fleeing Kuwait with hundreds of thousands of other Palestinians following the 1991 Gulf War. She was working in marketing for Apple Computers when she met Prince Abdullah two years later. At the time, it was expected that King Hussein’s brother would succeed him, but on his deathbed the king promoted his eldest son.

More recently, Rania has been at the forefront of a call for support for more than half a million Syrian refugees currently living in Jordan, one of six of which lives in abject poverty according to a recent UN report. "While Jordan is small in size, it is big in its national and humanitarian sense of responsibility," she said in her keynote speech at a recent summit about support for child refugees. "The world has come to know very well it can rely on Jordan in difficult humanitarian crises. And the world has a major role in supporting all countries hosting refugees, because that is a guarantee of our region’s stability.” She has also addressed world leaders with a more generally international but still urgent campaign to eradicate poverty, tackle inequality, and prevent further climate change.

With her supermodel looks, English accent, and progressive agenda, Rania gets adoring notices in the Western world; she has been interviewed on Oprah, and her children’s book, The Sandwich Swap, which conveys a message of cultural tolerance through a tale about schoolgirls sharing lunchtime snacks of peanut butter and hummus, was a New York Times best seller. In Jordan, however, where her husband King Abdullah II is not popular, she has been criticized for indulging in a lifestyle that is too extravagant and Westernized. In 2011, in a rare display of criticism of the royal family, 36 tribal leaders accused her of promoting herself to the extent that she was “a danger to the nation and the structure of the state and the political structure and the institution of the throne.” According to various press accounts, Rania began to dress more conservatively and lower her public profile. Still, she remains committed to her “day job.” “I am an Arab through and through,” she insists. “But I am also one who speaks the international language.”

His Highness, Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum

By Sandra Salmans

His Highness is using one of the largest charitable donations in history to ignite effective human development across the Arab world.

Memories are long in the Arab world. So perhaps it was not surprising that, when he announced plans nearly eight years ago to create a foundation with a gift of $10 billion, one of the largest charitable donations in history, His Highness Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum harked back nostalgically to the Bait al-Hikma (the House of Wisdom), which was a center of learning during the Islamic golden age of the 800s. “I have always asked myself, ‘Why doesn’t the House of Wisdom come back renovated in the Arab capitals?’” said Sheikh Mohammed, 65, who is prime minister of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and constitutional monarch of Dubai.

Now, through his Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Foundation and other philanthropic efforts, Sheikh Mohammed—whose net worth Forbes estimates at $18 billion—is trying to answer his own question. The foundation is intended to bring the next generation of Arabs more fully into the knowledge economy, focusing on three areas: culture, entrepreneurship and employment, and knowledge and education. So far, the foundation has invested in literacy (for example, pledging 100,000 books to children in the Arab world as well as grants to children’s book authors) and international exchanges of ideas, including conferences and access for its own fellows to prominent universities in the U.S. And like Bait al-Hikma 1,300 years ago, the foundation has supported the translation into Arabic of literary works from other countries. (The Sheikh is himself a prolific composer of traditional Nabati poetry.)

As the popular saying goes, it’s good to be the king, and that’s certainly true in Dubai. The foundation is the most ambitious—and lavishly endowed—of Sheikh Mohammed’s philanthropic undertakings, but it has plenty of company. From the moment he took over the reins of the UAE and Dubai from his elder brother in 2006, Sheikh Mohammed plunged into projects aimed at educating, empowering, and uplifting not only the Middle East but the entire developing world. His first step was to create the Dubai Harvard Foundation for Medical Research, to replicate the Harvard Medical School research model and bring the best training, research, and healthcare practices to Dubai, the Gulf, and the Middle East.

He has also sponsored a number of other philanthropic initiatives; while it’s unclear whether they receive direct contributions from his foundation, they benefit from his name and influence. They include Dubai Cares, which helps children in developing countries obtain an education, partly through providing them with school meals and healthcare such as deworming, renovated classrooms, and trained teachers; Dubai Foundation for Women and Children, the first licensed non-profit shelter in the UAE for women and children who are victims of domestic violence, child abuse, and human trafficking; and Noor Dubai, which provides health services to visually-impaired people in the developing world. Recently a UAE-based foundation announced the launch iof a $1 million annual prize for “the world’s greatest teacher”—a “Nobel Prize” for education, the press release declared, “under the patronage of His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum.”

Len Blavatnik

By Doug White

A Soviet emigrant to the US, Blavatnik is becoming a generous establishmentarian in education and beyond.

“Leonard Blavatnik is making possible a new way for Oxford to contribute to the world.” So began the September 2010 tribute by Lord Christopher Patten, Chancellor of the University of Oxford, in his remarks acknowledging Blavatnik’s “once-in-a-century” $120 million gift, which established Europe’s first major school of government at the oldest university in the English-speaking world.

Blavatnik, like many other donors with an eye on making transformational gifts, is not new to philanthropy.

Through his family foundation, he recently donated $50 million to fund the “Blavatnik Award for Young Scientists” at the New York Academy of Sciences. The money is helping to expand the number of people who are eligible to receive the award, which will now be open to faculty-rank scientists across the United States age 42 or under. The idea of “young” is key. According to Eric Lander, a director of the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, “Young scientists drive scientific discovery and innovation. They feel urgency and impatience. They think creatively and boldly. While we must support promising scientists at all levels, young scientists are a critical resource that we must nurture for the good of the whole scientific enterprise.”

But while academic pursuits feed the mind and eventually improve lives, Blavatnik is also putting his money where it will have immediate impact on people who desperately need it. He gives much every year to Colel Chabad, an Israeli charity that operates a network of soup kitchens and food banks, dental and medical clinics, daycare centers, widow and orphan support, and immigrant assistance programs. Founded in 1788, Colel Chabad is the oldest continuously operating charitable organization in Israel. Blavatnik’s support provides food every month for 5,000 families in 25 Israeli cities and towns.

In 1978, during a period of mass emigration for Soviet Jews, Blavatnik left his home in the Soviet Union for the United States. After then earning advanced degrees at Columbia and Harvard, his business career took off. He founded and is chair of Access Industries, a privately held multi-national company headquartered in New York, that invests in natural resources and chemicals, media and telecommunications, and real estate. In 2011 a subsidiary of Access bought the Warner Music Group for $3.3 billion.

As his generosity shows, Blavatnik tends not to think of starting new charitable enterprises; what makes his gifts noteworthy is his well-funded focus on improving what’s already working. There might be no better example, and thus an explanation for his comfort in giving away so much of his wealth, than his bet on one of the world’s premier educational institutions—a grand gesture meant to fuse history with the future. In Lord Patten’s words: “Oxford will now become the world’s leading center for the training of future leaders in government and public policy—and in ways that take proper account of the very different traditions, institutions and cultures that those leaders will serve. It is an important moment for the future of good government throughout the world.”

True enough. But even so, his gifts might say as much about the man, and his vision of what’s right in the world, as it does about the institutions that he supports.

Terrorist Funding and Philanthropy

By Suzanne Reisman

One person's terrorist may be another's freedom fighter.

Atrocities, biological warfare, carnage. Aid, best practices, country building. Such are the ABCs of philanthropy in war-torn countries like Syria and the Sudan. While one person’s terrorist may be another’s freedom fighter, the same tragedies are suffered by all sides. And philanthropists who try to alleviate that suffering must negotiate their own minefields, strewn with a morass of government regulation and the threat of fines and criminal prosecution.

Syria is a prime example. It is common knowledge that while the world watches the unimaginable atrocities visited upon its civilian population, donations are frequently intercepted by members of ISIS (otherwise known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria). In some instances brave individuals are driving cash and supplies over the borders, attempting to ensure that philanthropic aid is not diverted before it reaches its intended beneficiaries. The Charity Commission of England and Wales has recently published guidance that acknowledges the importance of providing humanitarian aid to those in Syria while warning of various obstacles, which in addition to the obvious physical dangers, include inadvertently engaging in terrorist financing. Syria is subject to a broad sanctions program administered by the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Financial Assets Control (OFAC) in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security, which apply to all U.S. citizens as well as U.S. entities such as private foundations and other 501(c)(3) organizations. U.S. charities that wish to make donations to Syrian charities must apply for a license from OFAC. Otherwise donations may be made to a U.S. charity that is registered under the OFAC Syria sanctions program or to a charity in a third country.

The most prudent and, in many cases, the most effective strategy is to work through NGOs with significant experience in the region. A Gulf-based donor with close ties to Syria has suggested that Médicins Sans Frontières, as well as the Maram Foundation and Karam, both of which are U.S. charities, continue to be successful in delivering aid to those affected by the Syrian crisis. The Maram Foundation runs the Atmeh Refugee Camp in Idleb, Syria’s largest refugee camp for internally displaced people, providing all food, medical and hygiene supplies. Karam operates a range of projects on the ground within Syria, including vital food distribution, and social and educational projects.

Of course Syria is not the only country in need of humanitarian assistance. It is however, along with Burma (Myanmar), Cuba, Iran and the Sudan, the subject of comprehensive OFAC sanctions programs. Sanctions and other anti-terrorist legislation have long been a part of governments’ foreign policy arsenal.

Various governments and international organizations (including the Financial Action Task Force, the European Union, and the United Nations) have issued guidance and sanctions in an effort to combat terrorism. Various countries, including the United States and the European Union, have also enacted anti-bribery legislation that impacts charities. The regulations and guidance issued by OFAC and the U.S. Department of Commerce include detailed guidance for U.S. donors and their foundations. They are also relevant for non-U.S. donors who may wish to fund projects by making grants to or partnering with U.S.-based NGOs. OFAC has also issued “Anti-Terrorist Financing Guidelines: Voluntary Best Practices for U.S.- Based Charities” which are, as the name suggests, voluntary but may be useful to many donors. (These guidelines in particular have also been the subject of significant criticism.)

As a general matter, donors may begin their due diligence by reviewing the “Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List,” or SDN list, published by the United States and the United Kingdom’s consolidated list, which includes those persons and entities on the European Union’s and United Nations’ lists. The U.S. list includes individuals and entities throughout the world (including the United States) that are designated due to their activities in targeted countries as well as others such as terrorists and narcotics traffickers. Regardless of whether an entity or individual is on an SDN list, donors are required to undertake their own due diligence to determine if they are providing assets or services to entities that are owned, controlled by or acting on behalf of a person or entity on the SDN list.

The SDN lists can be problematic. Once an individual or organization appears on the list, it can be difficult to get off, regardless of circumstances. On July 18, 2013, the European Court of Justice issued an opinion confirming that the procedures used to list the plaintiff, whose removal from the list had been recommended over 10 years ago by the United Nations, were flawed. One U.S. court has found that the U.S. government froze charitable assets without probable cause, in violation of the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. A second district court determined that illegal wiretaps were used to gather evidence supporting inclusion on the SDN list; however on appeal it was determined that the government had not waived sovereign immunity and the district court decision was vacated. OFAC issued guidance in 2010 relating the release of limited amounts of blocked funds to cover legal fees and costs incurred by U.S. persons who seek to challenge their designation as blocked persons.

The next step for charities interested in countries subject to sanctions programs is to review the relevant sanctions. Broadly speaking, the comprehensive sanctions programs allow for philanthropic activity through either general licenses (which may require reporting but do not require a license before the activity takes place) or specific licenses, which apply specifically to the applicant. Sanctions programs are subject to change at any time—changing even as this article was written. Donors are encouraged to continuously monitor OFAC licensing procedures and related guidance and regulations.

The United States first imposed sanctions on Burma in 1988 when it suspended aid to the country after the shooting of protesters by the military junta. Humanitarian assistance was permitted to continue. In light of the momentous changes that have taken place in the country over the past few years, the United States has eased its policy, paving the way for full economic engagement with Burma, while at the same time providing safeguards in the event that the Burmese government changes its policies. Sanctions relating to philanthropy have been eased accordingly. In April 2012, OFAC expanded the types of support for humanitarian, religious and other non- profit activities that could be provided in Burma, provided that they do not benefit any “blocked persons.” These developments should also pave the way for the creation of micro-finance projects in Burma.

Up until the recent announcement of reinstated relations between the two countries, OFAC maintained a comprehensive sanctions program against Cuba, and a new FAQ published by the Treasury Department updates the information as of January; licenses are available for a wide variety of philanthropic undertakings. The thawing of U.S. relations with Iran, historically referenced as part of the “axis of evil,” is also evident in the easing of OFAC’s sanctions programs. On September 10, 2013, OFAC issued two new general licenses as part of the Iran Transactions and Sanctions Regulations. One authorizes NGOs to export services to Iran in support of non-profit activities, subject to certain reporting requirements and a cap of $500,000 on the transfer of funds over a 12-month period. The other authorizes the importation and exportation of certain professional and amateur sports services and exchanges, including activities related to exhibition matches, sponsorship or players coaching, refereeing and training.

OFAC sanctions apply differently to different regions of the Sudan and to a large extent no longer apply to the Republic of South Sudan, which gained its independence in 2011. Generally, humanitarian relief is permitted in Darfur and “specified regions” of Sudan and favorable licensing policies are applicable in other regions. It appears that relations with the Sudan may be easing as well in light of a deal struck between the U.S. company, General Electric, in the Sudan and a reported statement by Sudanese Foreign Minister Ali Kharti that several U.S. companies which applied for licenses to operate in Sudan were granted, which he believes “is an indicator that investments and commercial relations could overcome political difficulties.” In the meantime, it is permissible to donate articles that relieve human suffering such as food, clothing and medicine.

The United States has targeted programs which prevent individuals from doing business with blocked persons in Somalia, Western Balkans, Belarus, Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Liberia (Former Regime of Charles Taylor), Persons Undermining the Sovereignty of Lebanon or Its Democratic Processes and Institutions, Libya, North Korea, Somalia and Zimbabwe, as well as other programs targeting individuals and entities around the world. In certain cases OFAC has been more flexible. For example, the U.S. Treasury website’s Frequently Asked Questions regarding private relief efforts in Somalia recognize that, due to the highly unstable environment and urgent humanitarian needs in the country, some food, medicine or payments may unintentionally be provided to al-Shabaab, a terrorist group. The FAQs state that, so long as the donor did not have reason to know it was dealing with al-Shabaab, “such incidental benefits . . . would not be a focus for OFAC sanctions enforcement.”

Legitimate concerns have been raised about the breadth of the power that governments may marshal to investigate and audit philanthropic endeavors and freeze assets. Depending on where one’s sympathies lie, these sanctions may be seen as necessary or the misguided edicts of Western governments. Some jurisdictions such as the European Union have promulgated regulations prohibiting compliance with U.S. sanctions where they conflict with the EU’s. Furthermore, the applications of sanctions may differ, based on whether the individual or entity is a charity, a corporation, or a branch of the U.S. government.

Chiquita Brands International Logo

Chiquita Brands International LogoTake, for example, the case of Chiquita Brands International (“Chiquita”), which through its Banadex Unit owned banana operations in Colombia. From 1997 to 2004 Banadex made payments to United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (also known as AUC), a violent paramilitary and drug trafficking organization, for protection from guerrillas that had previously murdered Chiquita employees. As of September 10, 2001, it was a crime to finance AUC. In 2004 Chiquita sold Banadex to Banacol, which then provided bananas to Chiquita. Chiquita was subsequently indicted by the U.S. Department of Justice in connection with its payments to AUC, and in 2007, pled guilty to doing business with a terrorist organization and paid a $25 million fine. However “Chiquita turned a $49.4 million profit from its Colombia operations during the period while it was making the illegal payments to the AUC. . . . Defendant Chiquita’s payments may have protected its workers while they were working on the company’s profitable farms, but Defendant Chiquita’s payments field the AUC’s terrorist violence everywhere else.” During the sentencing hearing Chiquita’s lawyer noted that Chiquita had voluntarily approached the Department of Justice when it asked whether it should stop making payments, the government’s response was equivocal. The “government did not want to say ‘stop’ explicitly because it did not want to have blood on its hands if someone was, in fact, killed. It couldn’t say ‘continue’ because it did not want to hurt its case and so it looked for...a middle ground.”

If a charity made payments to a “specially designated global terrorist” its assets would be frozen and likely its directors would be subject to prosecution. Apparently when a corporation makes such payments, it is one of the costs of doing business in Colombia.

Could Chiquita’s predicament have been resolved if NGOs had trained managers to use nonviolent methods of conflict resolution? In Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that it was a crime for a U.S. NGO to train Kurdish and Tamil groups on the SDN list to use peaceful methods of reaching their objectives, such as petitioning the United Nations and other entities and to engage in political advocacy for groups. Ironically while everyone’s stated wish is “world peace,” it is a crime to assist terrorists to find peaceable methods of making themselves heard on the world stage. While it is understandable that tax relief is denied those who assist parties who are not in alignment with U.S. foreign policy, providing groups designated as terrorists with alternatives to terrorism is also a laudable result.

While donors are required to follow these rules under threat of civil penalties and criminal prosecution, the U.S. government struggles to end its own terrorist financing. In his July 2013 Quarterly Report to the U.S. Congress, John F. Sopko, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) expressed concern about 43 cases in which material “supporters of the insurgency” in Afghanistan, including supporters of the Taliban, the Haqqani Network and al-Qaeda, had received government contracts. SIGAR reported that the Army Suspension and Debarment Office declined to act on these cases as it would violate the contractors’ due process rights if they were suspended or disbarred based upon classified information or findings of the Department of Commerce. Sopko concluded: “I am deeply troubled that the U.S. military can pursue, attack and even kill terrorists and their supporters, but that some in the U.S. government believe we cannot prevent these same people from receiving a government contract. I feel such a position is not only legally wrong, it is contrary to good public policy.... I continue to urge you to change this faulty policy and enforce the rule of common sense in the Amy’s suspension and debarment program.”

The Persistence of Philanthropy

By Amy Singer

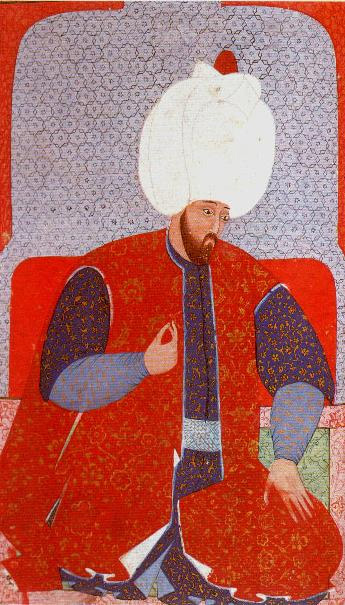

One of the most profound Ottoman legacies to modern Turkey is a long history of private philanthropy.

I fell into the study of philanthropy while trying to make sense of rural taxation and land tenure in 16th century Palestine, then under Ottoman rule. Several weeks in the imperial archives of the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul brought me face-to-face with an exquisite series of long scrolls penned in gold, lapis, and black inks some five hundred years old. They recorded orders from Sultan Süleyman “the Magnificent” to transfer properties to his wife, Hurrem Sultan. From these she immediately created an endowment, a waqf, to support a public utility in the middle of Jerusalem, a space allocated for what we may now consider a soup kitchen, serving meals twice a day.

Ottoman sultans, and in fact Muslim rulers and their families since early Islamic times, made large endowments to support schools, mosques, roads, hospitals, baths, bridges, cemeteries, as well as the odd idiosyncratic fund to care for cats or feed birds in the winter. Founding public works was part of their job description, a function sandwiched between religious leader and politician. Meanwhile, individuals with any means often made their own endowments of every possible size, funding public welfare and their own families in the process. This type of giving is a common encouragement throughout the Qur’an as well as the Old and New Testaments.

The specific Ottoman cases also raise more universal questions about philanthropic giving. How voluntary is voluntary? Why do some gifts earn praise and others a shrug? What does practical altruism mean and does it really exist? Where do the boundaries lie between individual initiative and government responsibility? Who decides which people deserve to benefit from philanthropy (like who gets to eat at a public kitchen)? These types of questions offer insights from the past to today’s philanthropists, who in the very nature of their work look to the future.

Historians examine the past to understand how people functioned in societies and cultures in times preceding our own. We try to understand what people valued in the past, what worried them, how they coped with threats, what they celebrated and why, and what precipitated changes in their lives. We ask questions about how people did what we still do: make a living; pray; raise children; build; ail and heal; fight wars; trade. These constants link humans across space and time through experiences that are at the same time very similar and utterly distinct.

Philanthropy—voluntary giving of material wealth, time, and expertise for the benefit of individuals or communities—is one of those constants, persistently present. It is for this reason that a column written by an historian just might be of interest to an audience of contemporary philanthropists and philanthropic professionals. History not only enriches our lives by explaining how change comes about in the world but it connects us to people who participated in those changes. Our own world is more dynamic, complex, beautiful, and simply bigger when we understand more about someone else’s.

Her Royal Highness Princess Bandari Bint Abdulrahman Al Faisal

By Julie Shafer

The Princess has a clear definition of successful philanthropy and, in her view, being a woman in Saudi Arabia is a plus.

In a country where women aren’t allowed to drive, let alone vote, hold office, or do much of anything without a male guardian, what kind of role can a woman play in philanthropy? In Saudi Arabia, a significant one, in the admittedly exceptional case of Her Royal Highness Princess Bandari bint Abdulrahman Al Faisal. Princess Bandari has been the Director General of the King Khalid Foundation since its inception in 1999.

To a degree, she was groomed for the job. Her mother and grandmother were active role models of formal and informal philanthropy throughout her childhood. To ensure that she was not a “spoiled” child, they would have her accompany them on visits to nonprofits to listen to discussions on women’s rights, roles, and responsibilities within their community.

After graduating from Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government with a master’s in public policy in 1998, Princess Bandari accepted the Directorship with some reluctance. She was apprehensive about her preparedness and qualifications for the role, but her gender wasn’t an obvious disqualifier. In fact, women in Saudi Arabia have frequently assumed The King Khalid Foundation leadership positions in foundations, nonprofits, and non-governmental organizations. (And, starting in 2015, they will be allowed to participate in the elective process.) If anything, the Princess says, her gender is a bonus—she’s allowed to be more aggressive and outgoing and “has nothing to lose.”

Although the Princess is traditional in many ways—for example, she has described the enveloping abaya as a relief because she doesn’t have to decide what to wear—in some respects she has been surprisingly bold. Last year, for example, she gave the go-ahead for a newspaper advertisement against domestic violence—a striking full-page picture of a woman with a black eye clearly visible under her burqa. Underneath the image a slogan read, “Some things can’t be covered,” and a list of phone numbers for local domestic abuse shelters. As the country's first-ever anti-domestic abuse advertisement, the campaign was as shocking as it was powerful, but Princess Bandari, who approved it, says she doesn’t understand the controversy. “My media and PR team were a bit nervous going into this, saying, ‘Are you sure you want to do this?’ I didn’t understand why. I don’t understand what is so controversial. Who will say, ‘Yes, it’s okay for women to be beaten up’?”

During her tenure, Princess Bandari has worked to build formal structures within the foundation, institutionalizing measurements and evaluations. She was handed a blank canvas and admits that making mistakes fast became part of her learning process. The Princess describes her management style as “growing organically” and strives to keep up pressure on the foundation’s impact not only for her local community but for the entire country.

One of the most critical discoveries has been the overwhelming need for capacity building in Saudi Arabian nonprofits. Princess Bandari focuses first on sustainability, not dependency. The foundation assists with strategic planning, mentoring and program development. Bandari has coached philanthropists and other foundations in the realities on the ground, including the need for program-building funds to ensure a robust nonprofit system.

And, perhaps to ensure continuity, she has also established the Princess Bandari Al Faisal Fellowship at the Kennedy School to support students from the Arab League. Women applicants get preference.